Today is Equal Pay Day, the day that marks how far into the next year women on average have to work to bring home the same income men earned in the previous year. In light of Equal Pay Day I published an op-ed in the Washington Examiner that looks at women’s opinions about the gender pay gap. What I found might surprise you:

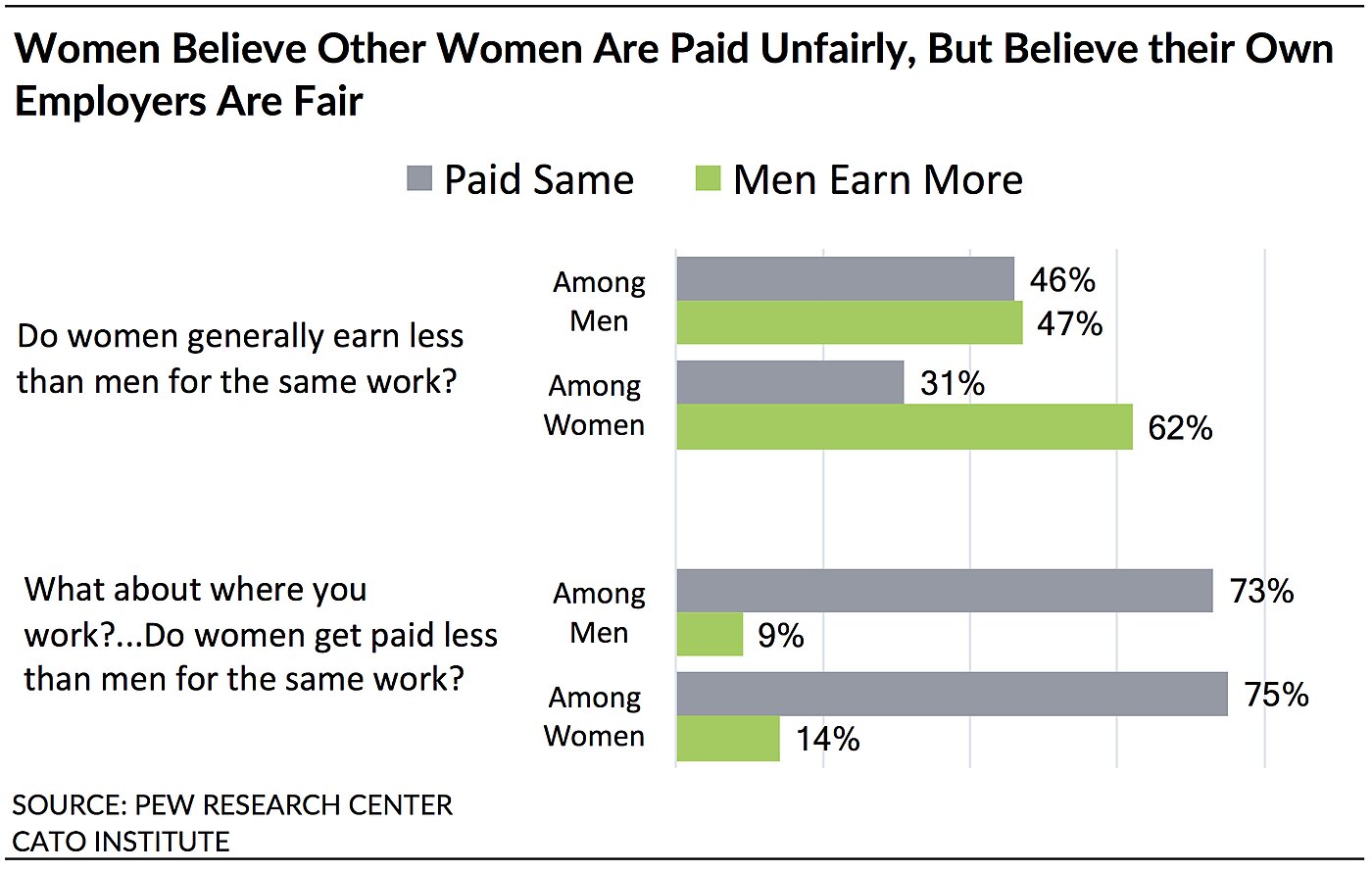

A Pew Research Center survey found that 62 percent of women believe that women “generally” get paid less than men for doing the same work. However, when asked about their own companies, far fewer — just 14 percent total — believe women are getting paid less than men where they work, and 17 percent say women have fewer opportunities for promotions where they work.

These are nearly 50-point shifts in perception from what women believe is generally happening in society at-large, and what they collectively report is happening based on their experiences in their own jobs.

This in no way discounts the negative experiences women have had, and we should not shy from denouncing inequitable treatment. Yet these data also reveal that although most women believe they are being treated fairly, they also believe that most other women aren’t.

These data indicate that women have come to believe the myth that women are getting paid less than men for doing the same work. However, academic studies show that gender discrimination is not largely influencing wages, as I explain in the op-ed:

Although Census data show that women make less money on average than men, this fails to consider any information about how women and men choose to pursue a work/life balance, whether they enter a career that requires 80-hour work weeks or 40-hour work weeks, whether they take time out of the workforce to raise children, how much education they attain, whether they go into careers like investment banking or education, surgery or nursing, etc.

Studies that take these other factors into account find that the gender pay gap narrows to about 95 cents on the dollar. The remaining 5 cent difference might be due to discrimination, or it might be due to differences in salary negotiations, or other reasons. Harvard economist Claudia Goldin writes, “The gender gap in pay would be considerably reduced and might even vanish if firms did not have an incentive to disproportionately reward individuals who worked long hours and who worked particular hours.”

The Pew Survey found several disconnects between what women believe is causing the gender pay gap and the empirical research. First, Pew found that 54% of women believe that gender discrimination is a “major reason” for the pay gap. Although gender discrimination in pay can occur and should be sharply rebuked, research finds it is not significantly impacting wages.

Second, although differences in the number of hours men and women work (and when those hours are worked) is a significant driver of the wage gap, most women don’t find this believable. Only 28% thought this was a “major reason” that women on average earn less than men. Perhaps it sounds like one is accusing women of being lazy. Just because men on average work more hours in an office setting doesn’t mean women aren’t working the same or more hours when you combine hours worked in the office and taking care of family and home responsibilities.

Women responded better to the idea that men and women on average make different choices about how to balance work and family responsibilities and that might explain differences in pay. In fact, this was the most likely reason selected with 60% of women saying it was a major reason men and women earn different incomes.

As we talk about Equal Pay Day and the gender pay gap, it’s important to keep in mind both the empirical facts and where people are coming from. Some women have experienced discrimination in their jobs and such treatment should be condemned. We also need to be mindful about how we explain the sources of the gender pay gap, and avoid suggesting women aren’t working as hard as men.

Furthermore, in light of Equal Pay Day, we should point out the potential harms caused to women by perpetuating the idea that there is widespread injustice set against them. If women believe the deck is stacked against them regardless of their choices, this risks undermining risk-taking, accountability, and initiative.

You can read the whole op-ed at the Washington Examiner here.