Speaking today at a Whirlpool factory in Clyde, Ohio, President Trump will credit his January 2018 decision to impose 50% “safeguard” tariffs (at Whirlpool’s request) on imported washing machines with creating 200 Ohioan jobs and spurring new domestic investment in appliance manufacturing across the country — a testament to the President’s economic nationalist policy and vision. Continuing that vision, Trump will also announce he’s signing an Executive Order that “instructs the government to develop a list of ‘essential’ medicines and then buy them and other medical supplies from U.S. manufacturers instead of from companies around the world.”

If news reports are correct, however, President Trump will omit several crucial details about Whirlpool and his washing machine tariffs – details that caution against following a similar economic nationalist path for essential drugs and other medical goods.

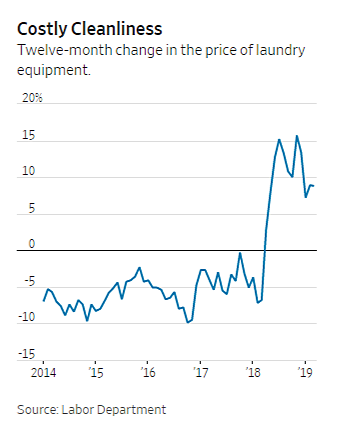

- First, those tariffs dramatically raised prices for both washers and dryers, which economists last year calculated cost American consumers an additional $1.5 billion per year. Had U.S. retailers been unable spread out the washers’ cost increase to dryers, that already-high 12% price increase would have almost doubled. Given these higher costs, and even factoring in the additional tariff revenue collected by the U.S. government, the researchers found that – even under the rosiest job creation scenario — each new American appliance manufacturing job cost U.S. consumers $817,000 per year. Yikes.

- Second, according to an August 2019 examination of the tariffs’ effects by the United States’ International Trade Commission (ITC), which recommended the tariffs and is required by law to review them periodically, the tariffs have not produced a thriving domestic industry. Although capacity and employment reportedly increased, for example, actual production declined, “resulting in declining capacity utilization, lower productivity levels, and higher unit labor costs.” (The ITC also noted the aforementioned price increases.) Indeed, Whirlpool itself told the Commission that the safeguard “has fallen short of delivering the intended remedial benefits to the continuously operating U.S. producers” due to “unanticipated” responses to the tariffs by foreign exporters (absorbing some of the tariff cost), U.S. importers (stockpiling), and consumers (buying fewer appliances). [Ed. note: all of these actions are common and expected market responses to tariffs.]

- Finally, it’s doubtful that President Trump will mention Whirlpool’s own financial difficulties – caused in large part by other Trump tariffs. In particular, Trump’s “national security” tariffs on steel and aluminum cost the company $300 million per year, collapsing its profits and stock prices (which peaked in January 2018 after the tariffs were announced but never recovered). Whirlpool was also affected by Trump’s “Section 301” tariffs on Chinese imports and unsuccessfully sought exclusions therefrom. (Economic nationalism for thee, but not for me.) The ITC’s 2019 report notes that other U.S. appliance manufacturers faced similar cost pressures due to the steel, aluminum and China tariffs (which raised all prices, not just those for Chinese imports).

None of this inspires confidence about the President’s new economic nationalist plans to revive domestic production of pharmaceuticals and other “essential” medical goods. Granted, at this stage President Trump’s new executive order sounds more like a campaign message than a serious policy change, and it involves Buy American rules, not tariffs. However, the administration has already announced subsidies for new domestic production of both pharmaceutical inputs and finished generic drugs – despite serious questions about the need and implementation of such plans – and economic nationalist policies have a long history of snowballing. (In fact, Trump’s washing machine tariffs were actually the third time that Whirlpool had petitioned and received government protection from imports.) It’s quite logical to assume that subsidized national champions making low-margin bulk commodities like generic drugs and their ingredients will seek more government help when faced with intense, lower-cost import competition, and that the government will at that point have a strong incentive to provide it.

If Trump’s washing machine tariffs are any indication, however, we should all hope that they pass on the chance – especially for something far more essential than a washer-dryer.