It’s nearing back-to-school time, and that means in addition to lots of yellow buses, we’ll be seeing the annual spate of education polls. The first one just came out—the 2019 Phi Delta Kappa poll—and it furnishes some interesting information illustrating why it’s so hard for public schools to inculcate values. Short answer: we just don’t agree on them, and a lot of people fear what their kids might be taught.

This edition of the survey—PDK, by the way, is an organization of professional educators—has a special focus on teaching religion, civics, and other values-based subjects, as well as presenting regular fare such as grades for public schools and lists of perceived “biggest problems.” Taken as a whole, it reveals that most people want values taught, but there is major disagreement about what values specifically, and the possible consequences of teaching them. It’s what we see play out in districts nationwide on Cato’s Public Schooling Battle Map, and no doubt in many places not on the Map because conflicts and concerns don’t make it onto reporters’ radars.

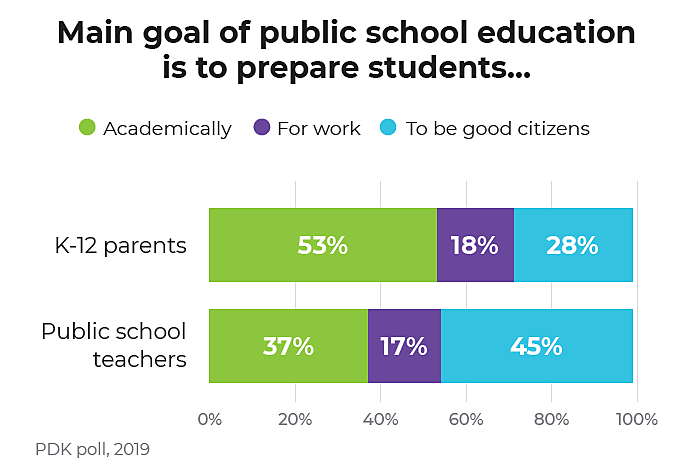

Start with civics. A central promise since the earliest days of American public schooling advocacy was that “common” schools would form good citizens. But to the extent that involves things like teaching how government works, it’s not happening. One reason may be that while those who are supposed to govern public schools—“the people”—overwhelmingly agree that civics should be taught, they don’t think it is nearly as important as other things. When asked what “the main goal of a public school education” should be, only 25 percent of respondents replied “to prepare students to be good citizens.” 21 percent said “to prepare students for work” and 53 percent “to prepare students academically.” The results specifically for parents, in the chart below, were similar.

The next problem is, if you do teach civics, what do you include? 27 percent of respondents, and 29 percent of parents, were at least “somewhat” concerned that “civics classes might include political content” with which they would disagree, with 35 percent of Republicans feeling that way. That’s less stark than one might expect if one thinks of such heated showdowns as those in Michigan and Texas over the core word “democracy,” but having more than one in four people fearing political bias means there’s a good chance of polarizing disagreement in lots of schools, making even basic civics something of a minefield to avoid.

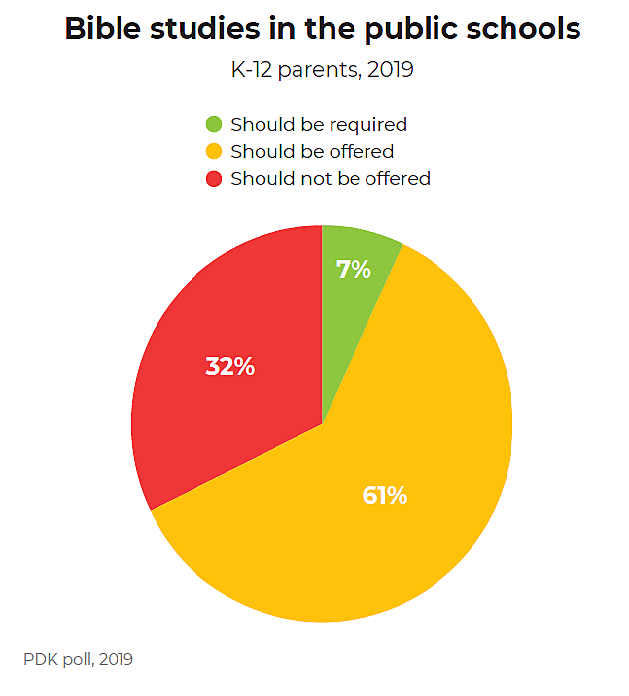

Even more precarious is religion, but many Americans are religious, and we have seen several states pushing to include religious content, especially on the Bible, in schools. The PDK poll shows that while almost everyone thinks civics should be taught, if not prioritized, feelings are more mixed on religion. On whether comparative religion classes should be in public schools, only 7 percent of respondents said they should be required, 70 percent supported them as electives, and 23 percent did not want them at all. Bible classes were more polarizing, with 6 percent wanting them to be mandatory, 58 percent electives, and 36 percent nowhere in the schools. (Again, as the chart below shows, parents were similar to the general public.) Tracking with this, about one in four respondents feared comparative religion classes would cause students to question their families’ beliefs or change their faith, and more than one in three feared Bible classes “might improperly promote Judeo-Christian religious beliefs.”

Again, those numbers may feel a little low, but having any sizable share of families potentially object to what is taught is a powerful deterrent against presenting the material. Indeed, while the pollsters found nearly unanimous approval for teaching generic “honesty” and “civility,” nearly 40 percent of respondents said it would not be possible to get people in their community “to agree on a set of basic values.”

All of this points to an inherent problem for public schools in a diverse society: It is very difficult get diverse people to agree on what to teach, especially on highly personal matters such as religion, or highly volatile such as politics. The result is that public schools often spark social conflict, downplay anything potentially controversial, or first do one and then the other, harming social cohesion and academic rigor. Of course, there is an educational arrangement that avoids the zero-sum nature of public schooling, fostering peace and rigor: school choice. This year, PDK did not ask about that.