Some day in January 2013, I got on a plane from Riyadh, the capital of Saudi Arabia, to Istanbul, the metropolis of Turkey. What made the otherwise unmemorable flight rather memorable was the dress code of some female passengers that changed dramatically from the departure to the destination.

In Riyadh, they all boarded on the plane all covered, from head-to-toe. When the plane approached Istanbul, however, I noticed some of these women walk back to the lavatory and emerge dressed in a very different fashion. Now, they were all wearing much more relaxed dresses—a few of which were quite revealing—along with heavy makeup. One woman, I can say, was wearing one of the shortest miniskirts I had ever seen. Apparently, she was ready to party in Istanbul’s famous nightclubs.

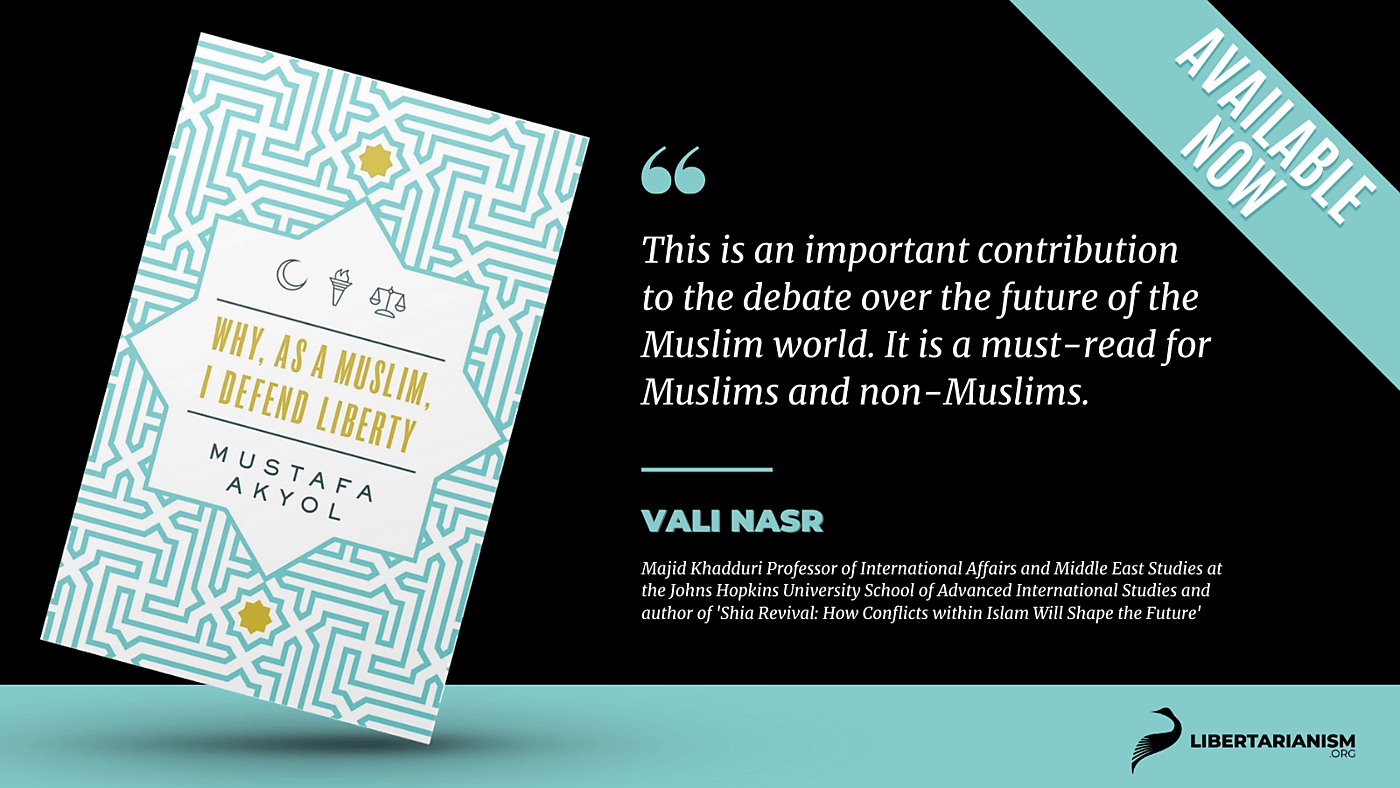

I tell this story in the beginning of my latest book, Why, As a Muslim, I Defend Liberty. The point I make out of it is a simple fact: Religious coercion does not lead to genuine piety. It only leads to hypocrisy. If people are forced to practice a religion, they don’t do it out of a sincere will to obey God. They do it out a disdained obligation to obey men.

This simple fact must be intuitively obvious to most people, but it isn’t to the mutawwa, or the “religion police” forces that Saudi Arabia has employed for decades, in order to discipline society in the name of God. The Islamic Republic of Iran is a similarly oppressive religious regime, as the “Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan” will now become, for the second time, under the harsh rule of the Taliban.

But the same simple fact — that coercion isn’t good for religion — wasn’t obvious also to many Christians, for many centuries. That is why they established theocratic kingdoms, persecuted “heretics,” and even tortured victims to “save their souls.” And that is why John Locke, the father of liberalism, had to write his 1689 classic, A Letter Concerning Toleration, in which he stressed:

“All the life and power of true religion consists in the inward and full persuasion of the mind; and faith is not faith without believing.… [So], it cannot be compelled … by outward force.”

In Why, As a Muslim, I Defend Liberty, I have several such quotes from John Locke, because I believe some of the problems he was addressing in the Christian doctrines of his day are quite similar to the problems we have in some Islamic doctrines of today. The parallel is also noted by Nader Hashemi, an American Muslim academic, who observed: “In much of the Muslim world today, as in Locke’s England in the seventeenth century… large segments of the population are under the sway of an authoritarian and illiberal religious doctrine.”

My book is largely a critique of this “authoritarian and illiberal religious doctrine.” But make no mistake: I am not challenging religion itself. I am only challenging its marriage with coercive power — with manifestations such religious policing, blasphemy laws, apostasy laws, supremacism over non-Muslims, or the doctrine of “obedience to the ruler,” a doctrine that Muslims tyrants love to use.

This critique requires a frank discussion of the Sharia — Islam’s legal tradition — which I offer in two subsequent chapters: 2 and 3. First, by showing some horrific results of the “implementation of the Sharia” in Pakistan — the persecution of rape victims as “adulteresses” — I call on fellow Muslims to “rethink” the Sharia. The key, I argue, is to look into the “intentions” behind religious rulings, instead of being blind literalists, as well as realizing that the Sharia is infused with medieval context and culture, which needs to be challenged, besides the universal tenets of Islam.

On the other hand, I argue in Chapter 3, there is also something to “learn” and even “revive” from the Sharia. Because, for centuries, in Islamic societies, the Sharia was the gatekeeper of a crucial value: rule of law. Because “God’s law” was above everyone, including the mightiest rulers, acting as a constraint on those rulers. When this traditional order was replaced with a bad form of secularization — inspired more by fascism than liberalism —authoritarian regimes dominated the Muslim world. So, liberalism is the right way forward, which, just like the Sharia of the past, will constrain rulers, and uphold the rights of all humans.

Then in Chapters 4 and 5, I use a thought experiment—an island-state established by shipwreck survivors—to reconsider the politics of Islam. Does Islam call for conquest and supremacy, as some Muslims believe? Or should Muslims cherish political systems based on contract and equality? (Or should they enjoy liberalism in the West as minorities, while championing supremacism where they make majorities, as an American Muslim leader recently suggested?) Meanwhile, does the Qur’an really oblige its believers to “obey” their rulers, leaders, or some other great men?

Chapter 6 addresses a common concern among Muslims: How can we allow all those irreverent atheists and offensive blasphemers to talk freely against our religion? Should we not silence them?

Chapter 7 goes into the economics of liberalism and see why that much-derided term, “capitalism,” is not alien to Islam but rather intrinsic to it, even in its conservative interpretations.

Finally, in Chapter 8, I get to a question that may haunt some Muslims the moment they hear the word “liberty,” let alone “liberalism”: Aren’t these the ideas of the colonizers that have invaded and plundered Muslim lands in the past 200 years? Why would we buy into their narratives? Is this some neocolonial conspiracy?

Surely, all these questions require much longer discussions than what I could summarize in the 150 pages of Why, As a Muslim, I Defend Liberty. Yet this little big book is meant to offer insights and challenge cliches, by elucidating complex ideas with personal anecdotes, historical episodes, and thought experiments that I am sharing for the first time.

So, you are welcome to read Why, As a Muslim, I Defend Liberty, by ordering online, or from the free PDF graciously offered by Libertarianism.org.

And you are welcome to view the live online book forum on Nov 21 I will have with Prof. Vali Nasr, who defined the book as “an important contribution to the debate over the future of the Muslim world” and “a must-read for Muslims and non-Muslims.”