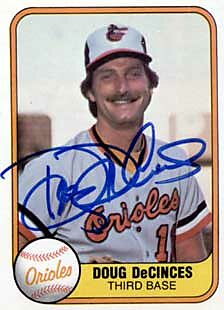

Kenesaw Mountain Landis, the legendary baseball commissioner, once said that every boy builds a shrine to some baseball hero, and before that shrine a candle always burns. Growing up a Baltimore Orioles fan during the franchise’s glory days, my shrine had many heroes, including central figures Cal Ripken (HOF 2007), Eddie Murray (HOF 2003), and John Lowenstein. Not central but still part of the shrine was Doug DeCinces, a good glove/solid bat third baseman who manned the O’s hot corner for nine of his 15 major league seasons.

And so I was saddened to read that last Friday DeCinces was convicted of 14 charges of insider trading.

Back in 2008, his neighbor, James Mazzo, then CEO of an ophthalmic surgical supply company, told DeCinces that the firm was about to be acquired by medical giant Abbott Labs. DeCinces owned stock in the firm and purchased more after he learned of the deal. He also shared the tip (though apparently not its provenance) with some friends, including Murray. DeCinces ultimately profited about $1.3 million on the deal according to press reports.

His maneuver seems inoffensive if shrewd; after all, who wouldn’t buy something that he can then sell at a profit? That is fundamental to the marketplace, and it typically makes all participants better-off.

But in DeCinces’ case it’s a crime, and a very serious one. He can receive as much as 20 years in federal prison for each of the 14 charges he was convicted on.

The question is why. Remember that all an inside trader does is act on private information that more accurately reflects the future value of some financial asset than the current price does. He buys or sells that asset at a price that someone else voluntarily accepts. He does nothing that damages (or falsely props up) the ultimate value of the asset. Nor does he hurt the broader financial marketplace; if anything, his trading slightly pushes the asset price toward a more appropriate value.

In fact, as Villanova law professor Richard Booth has explained in the pages of Regulation, it is the legal pursuit of inside traders that hurts other investors and the broader marketplace. Those prosecutions frighten would-be traders away from acting on—and thereby transmitting—their private information. The prosecutions also usually hurt the firms—which is to say the firms’ many innocent investors—because they end up paying large fines and legal expenses. For institutional investors—pension funds, 401k plans, etc.—those losses far outweigh whatever benefits might come from civil recoveries from insider trading and the phantom benefits of “policing” these activities. Really, the only beneficiaries from these legal actions are the well-heeled lawyers and government employees who participate in them.

DeCinces isn’t the first celebrity to be tripped up by fanciful claims of financial crimes. Recall Martha Stewart (pursued by one James Comey, interestingly) and Michael Milken (pursued by Rudy Giuliani), for just two examples.

According to press reports, upon hearing his conviction on Friday, DeCinces could only shake his head, dumbfounded. We should do the same. There is nothing for society to gain from sending him to prison, ostensibly for the rest of his life, for actions that don’t seem worthy of being deemed crimes, let alone federal felonies. Instead of locking away DeCinces and puffing up a new generation of Comeys and Giulianis, it’s time to reform America’s Kafkaesque finance laws.