Has America become a nation of homebodies? Yale law professor David Schleicher claims it has in a study published last week. In Stuck! The Law and Economics of Residential Stagnation, Schleicher outlines some of the legal and economic barriers to geographic mobility, like land use laws, homeownership subsidies, and occupational licensing. He goes on to argue that government policies depress geographic mobility rates.

Indeed, in 2016 the U.S. had the lowest relocation rate in seventy years. This is a problem, because low geographic mobility means some Americans are being left in the dust.

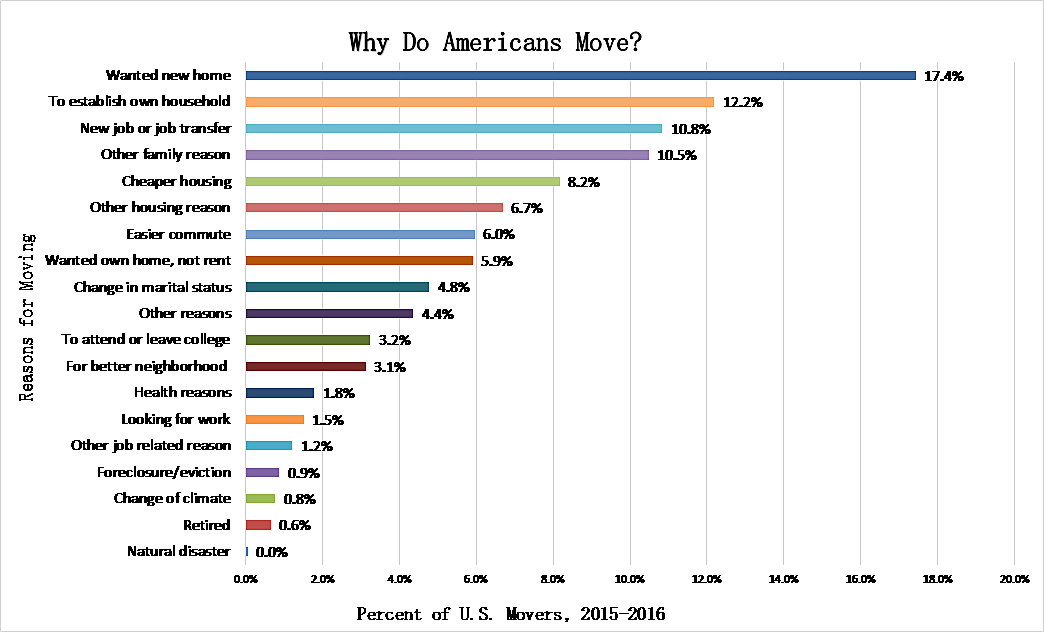

But in order to examine relocation trends, it is useful to understand why Americans relocate to begin with. U.S. Census data describes those reasons. Not surprisingly, the majority of Americans relocate for housing, job, and family.

Data source: U.S. Census Bureau, Geographical Mobility: 2015–2016

Schleicher reasons that many more Americans would move for housing and job-related reasons if it weren’t for existing government policies. That’s because a variety of policies make relocation more costly and remaining in place artificially attractive. Land use laws, homeownership subsidies, occupational licensing, and location-based subsidies distort individual’s decision calculus in harmful ways.

The impacts are not limited to the individual. For example, recent research on land use regulations suggests that when low-skill workers are deterred from relocating to high productivity areas, the whole economy suffers. Enrico Moretti and Chiang Hsieh argue that if just three U.S. cities – San Jose, San Francisco, and New York – adopted regulation typical of the median U.S. city, U.S. economic output would increase by 8.9 percent. If the estimate is correct, then the impact of reducing regulation in all restrictively regulated localities across the U.S. would be enormous.

But government policy doesn’t only make it difficult or impossible for Americans to relocate, it also can make it hard for cities to adapt in the face of decline. For example, housing stock and government operations need to be reduced, capital reallocated, and city’s geographic footprint(s) compressed. Resources should be used for something more productive than policing abandoned neighborhoods in a declining place.

Regulations get in the way here, too. Cities frequently prohibit citizens from living in mobile homes, tiny homes, and small or cheap housing. But this type of housing is the easiest to move, leave, or eliminate if abandoned. Meanwhile, environmental and land-use regulations make it hard to dismantle abandoned structures.

This leaves cities with the futile job of policing and providing city services in places that aren’t being used. The burden falls to remaining residents, and able residents flee as the costs of city maintenance rise and benefits of city living fall. Remaining residents are left to watch as their city’s decline accelerates.

The fact is, many Americans feel marginalized and left behind in the Trump era. Government policies exacerbate the situation and ensure they are. Schleicher’s article is a must-read reminder that much can be done to change that.

For more information on how government policies curtail opportunity, see Cato Policy Analysis paper Zoning, Land-Use Planning, and Housing Affordability.