In the pre-World War I era, the fiscal burden of government was very modest in North America and Western Europe. Total government spending consumed only about 10 percent of economic output, most nations were free from the plague of the income tax, and the value-added tax hadn’t even been invented.

Today, by contrast, every major nation has an onerous income tax and the VAT is ubiquitous. Those punitive tax systems exist largely because—on average—the burden of government spending now consumes more than 40 percent of GDP.

To be blunt, fiscal policy has moved dramatically in the wrong direction over the past 100-plus years. And thanks to demographic change and poorly designed entitlement programs, things are going to get much worse, according to Bank of International Settlements, Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, and International Monetary Fund projections.

While those numbers, both past and future, are a bit depressing, they also present a challenge to advocates of small government. If taxes and spending are bad for growth, why did the United States (and other nations in the Western world) enjoy considerable prosperity all through the 20th century? I sometimes get asked that question after speeches or panel discussions on fiscal policy. In some cases, the person making the inquiry is genuinely curious. In other cases, it’s a leftist asking a “gotcha” question.

I’ve generally had two responses.

1. The private economy can withstand a lot of bad policy, but there is a tipping point at which big government leads to massive societal damage. Or, to cite a specific example, the European fiscal crisis shows that the chickens have finally come home to roost.

2. Bad fiscal policy has been offset by good reforms in other areas. I explain that there are five major policy factors that determine economic performance and I assert that bad developments in fiscal policy have been offset by improvements in trade policy, regulatory policy, monetary policy, and rule of law/property rights.

I think the first response is reasonably effective. It’s hard for statists to deny that big government has created a fiscal and economic nightmare in many European nations.

But I’ve never been satisfied with the second response because I haven’t had the necessary data to prove my assertion.

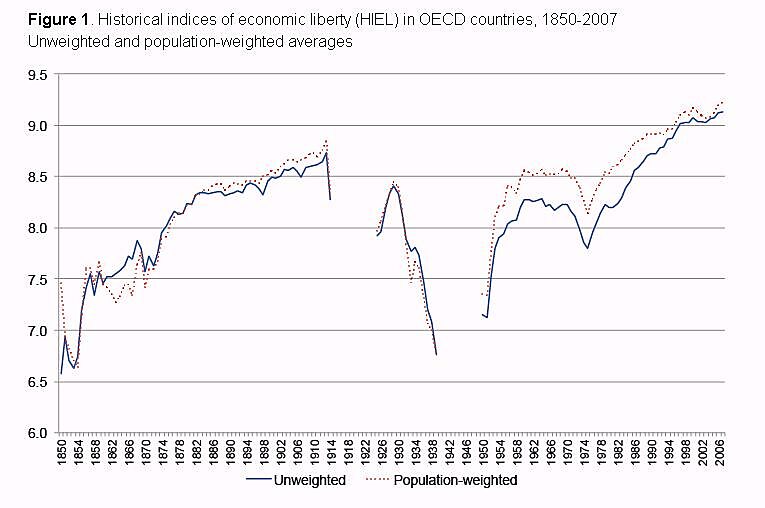

However, thanks to Professor Leandro Prados de la Escosura in Madrid, that’s no longer the case. He’s put together some fascinating data measuring economic freedom in North America and Western Europe from 1850 to the present. Since he doesn’t include fiscal policy, we can see the degree to which there have been improvements in other areas that might offset the rising burden of taxes and spending.

Below is one of his charts, which shows the growth of economic freedom over time. For obvious reasons, he doesn’t include the periods surrounding World War I and World War II, but those gaps don’t make much of a difference. You can clearly see that nonfiscal economic freedom has improved significantly over the past 150-plus years. Most of the improvement took place in two stages, before 1910 and after 1980.

It’s worth noting that things got much worse during the 1930s, so it appears the developed world suffered from the same bad policies that Hoover and FDR were imposing in the United States.

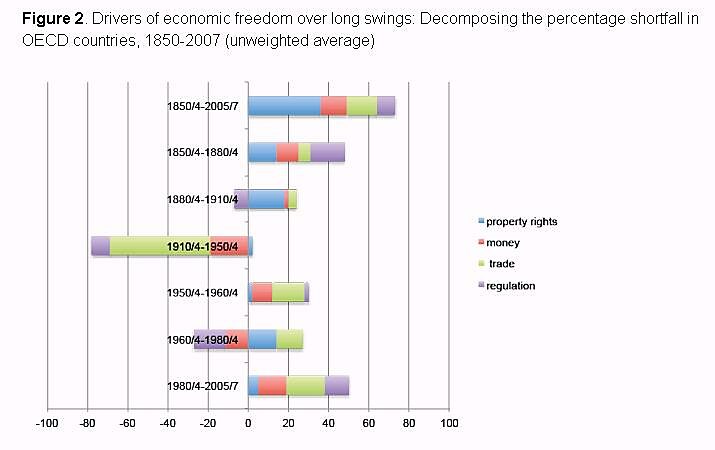

Below is another chart, which highlights various periods and shows which policies were moving in the right direction or wrong direction. As you can see, the West enjoyed the biggest improvements between 1850 and 1880, and after 1980 (let’s give thanks to Reagan and Thatcher).

There also were modest improvements in 1880–1910 and 1950–1960. But there was a big drop in freedom between the World War I and World War II, and you can see policy stagnation in the 1960s and 1970s.

By the way, I wonder what we would see if we had data from 2007–2014. Based on the statist policies of Bush and Obama, as well as bad policy in other major nations such as France and Japan, it’s quite likely that the line would be heading in the wrong direction. But I’m digressing. Let’s get back to the main topic.

The moral of the story is that we’ve been lucky. Bad fiscal policy has been offset by better policy in other areas. We’re suffering from bigger government, but at least we’ve moved in the direction of free markets. That said, we may now be in an era when bad fiscal policy augments bad policy in other areas.

For further information, this video explains the components of economic success: