Here we go again. The 2017 round of the Nation’s Report Card was released today. The results shouldn’t surprise anyone – they are almost entirely flat at the national level. However, that doesn’t stop educators and education reformers from spinning the results to fit whatever agendas they might have. Those who defend previous reforms claim that computer-based testing must be to blame for stagnant performance – and that students today are “relatively poorer” than they were in the past. On the other hand, groups calling for additional reform claim that the NAEP results should startle Americans.

We should all settle down. Here are 3 reasons why:

- Test scores tell us very little about success.

Education scholars such as University of Arkansas’s Jay P. Greene have been talking about the weaknesses of standardized test scores for a long time. Specifically, Greene frequently points out that at least 10 rigorous school choice studies indicate disconnects between effects on test scores and effects on long-term outcomes such as attainment and earnings. In fact, Diane Ravitch recently praised Greene for shining a light on this issue. And it’s not every day that Ravitch and Greene agree on something.

Research reviews indicate that Greene is on to something. For example, a recent review of the academic evidence on the subject finds that “there is a weak relationship between impacts on test scores and later attainment outcomes.”

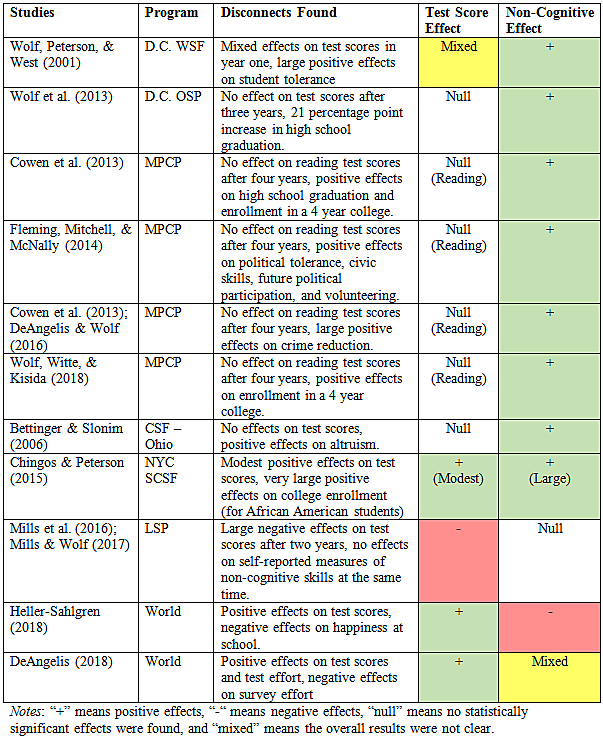

Similarly, I have started to review the causal private school choice literature that indicates divergences between effects on test scores and other long-run outcomes such as student criminality, effort, and happiness. As shown in the table below, I’ve found 11 disconnects in the literature since 2001. For example, the sample of students from the state-mandated evaluation of the Milwaukee voucher program saw no statistically significant improvements in reading test scores after the fourth year. However, those same students were more likely to enroll in a four-year college and less likely to engage in criminal activity later on in life. In other words, putting too much weight on standardized tests – like NAEP – could compromise the character development necessary for real lifelong success.

Studies with Disconnects Between Effects on Test Scores and Long-Run Outcomes

2. Even if test scores were strong measures of long-run success, changes in NAEP score averages alone do not tell us much about changes in nationwide performance.

Let’s assume test scores mattered. Even then, an uptick in NAEP scores wouldn’t necessarily tell us that overall performance improved. People like former U.S. education secretary Arne Duncan claim that the student population “is relatively poorer and considerably more diverse” than in the past. He may have a point. For example, single-parent households have nearly tripled since 1960. However, many scholars also point out that inflation-adjusted per capita income has nearly doubled since the 70’s, while the share of citizens with college degrees surged over the same period.

Since the magnitude – and the direction – of the student population’s relative advantage changes over time, we cannot confidently determine whether NAEP performance has actually gotten better or worse.

3. Even if test scores were strong measures of success, and we could somehow know that changes in NAEP scores reflected changes in nationwide performance, we would have no idea what policies affected those changes.

Now let’s also assume that – somehow – student advantage was held perfectly constant over time. Even then, we would have no idea what specific policies affected the changes in student performance. States that have different education policies have different populations and laws that could also affect their average standardized test scores.

Significant gains were made in Florida, for example. In fact, Florida was ranked the best-performing state for 4th grade math and reading scores after the Urban Institute controlled for several student background characteristics. But why? As a supporter of private school choice, I could spin these results in my favor by pointing to the fact that Florida has over 100,000 students participating in their privately funded private school choice program. But the truth is that the experts currently have no idea if the school choice programs in Florida have anything to do with the gains.

None of us should get this hyped up over standardized test scores. After all, these crude NAEP score averages unfortunately cannot tell us much of anything absent rigorous empirical analysis. Anyone claiming otherwise needs to slow down and reassess the situation.