The New York Times Magazine recently released its “1619 Project,” an initiative marking the 400th anniversary of the first African slaves arriving in North America. The project is ambitious, aiming to “reframe the country’s history, understanding 1619 as our true founding.” A collection of pundits have framed this project as an attempt to “delegitimize” the United States. Such commentary provides an opportunity to consider the state of American race relations and the role of slavery in American history.

Whether or not the foundation of the United States was legitimate is an interesting political, moral, and historical question. You can spend a career considering questions about when political violence is justified, what fair representation in a democracy looks like, how to measure and secure the consent of the governed, and what political system best secures natural rights. But these aren’t the kinds of questions many 1619 Project critics have in mind when they accuse it of “delegimitizing” the United States. They’re concerned that highlighting America’s brutal history of slavery and its role in forming the United States undermines the American project; an experiment in self-government.

The relationship between black people and the white institutions that oppressed them is one of the most consequential features of American history. The most prominent of America’s contradictions is that its Founding documents were written by white men who owned black human beings as farm equipment, yet they expressed a commitment to liberty.

Thomas Jefferson, the man who believed that it was “self-evident” that all men are created equal owned slaves. James Madison, the “Father of the Constitution” and author of many of The Federalist Papers, also owned slaves and was skeptical of free African Americans being a part of the American polity. After leaving the White House Madison served as the president of the American Colonization Society, which urged freed black people to move to Africa.

During the Revolutionary War, the British frigate HMS Savage sailed up the Potomac River, its troops burning houses in Maryland in view of Mt. Vernon, George Washington’s Virginia estate. The Royal Governor of Virginia John Murray had earlier issued a proclamation, offering freedom to slaves who fought for Britain. A wartime necessity rather an endorsement of full-throated emancipation to be sure, but it’s nonetheless telling that seventeen of Washington’s slaves fled Mt. Vernon and boarded HMS Savage. To a Virginia slave, housing in a British warship was preferable to the slave quarters belonging to the man who would become the first president of the United States.

Bewilderment at slave owners proclaiming a devotion to liberty is hardly reserved to 21st century. In a 1775 essay on the American colonies the English writer Samuel Johnson asked not unreasonably, “how is it that we hear the loudest yelps for liberty among the drivers of negroes?” The Founding Father John Adams never owned slaves and opposed slavery, though favored gradual erosion of the institution rather than outright and immediate abolition. His wife Abigail understood the contradiction of the American Founding:

I have sometimes been ready to think that the passion for Liberty cannot be Equally Strong in the Breasts of those who have been accustomed to deprive their fellow Creatures of theirs. Of this I am certain that it is not founded upon that generous and Christian principal of doing to others as we would that others should do unto us.…

That the Founding generation included moral hypocrites is hardly surprising. Every collection of human beings has included flawed people. Anyone scouring history books in search of moral perfection will be left disappointed.

It’s not clear that the moral hypocrisy of some of America’s founders delegitimizes the United States per se. At worst such hypocrisy makes the founding of the United States far from perfect. Even those who think that it’s a stretch to say that the United States was founded “on” racism can hardly deny that it was founded with racist institutions explicitly protected. The evils of slavery don’t in and of themselves negate the colonists’ complaints about a lack of representation in Parliament or the fact that British officials had subjected colonists to needless, intrusive searches and other abuses against their civil rights. But they shouldn’t be overlooked.

What is clear is that the United States has yet to fully come to terms with its history of racial violence and oppression. In large part this is because we’re accustomed to measuring our race relations progress through the lenses of military, political, and legislative victories.

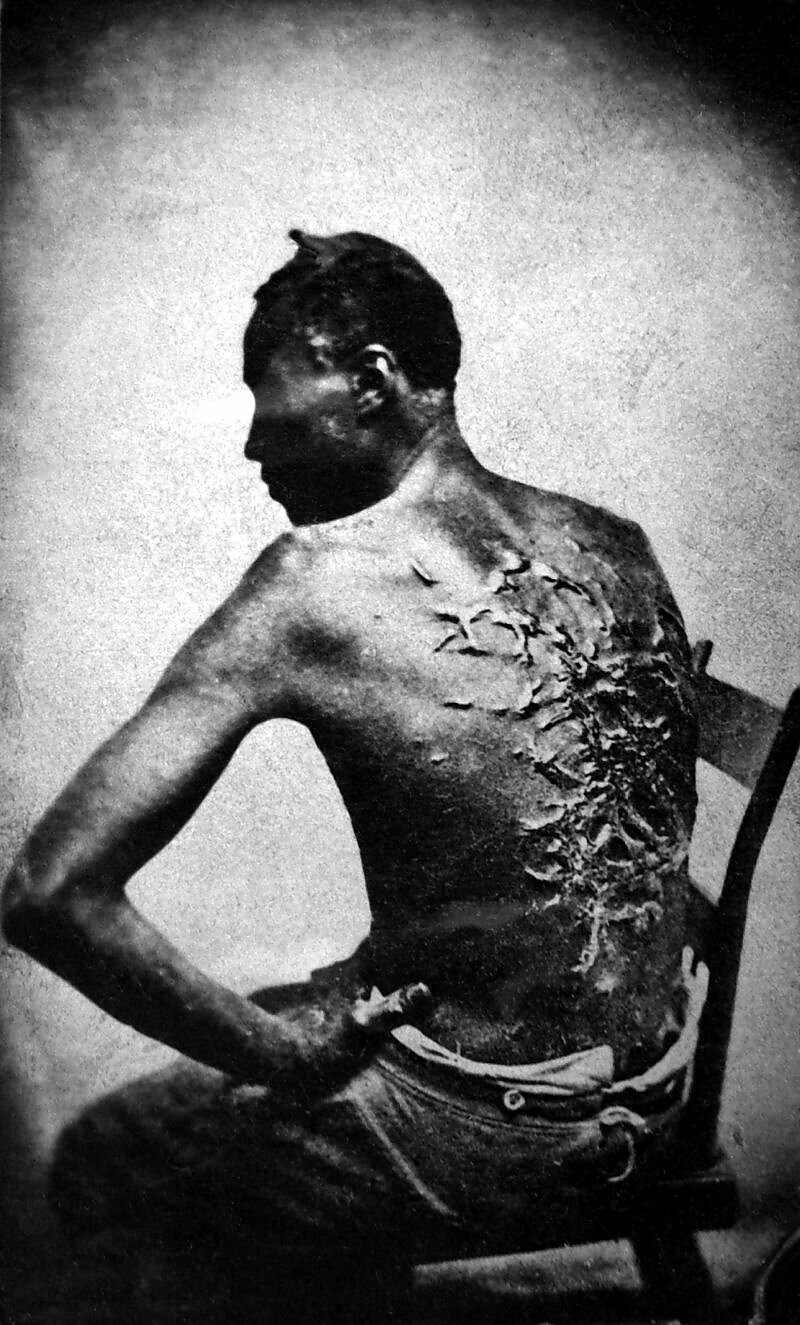

Hundreds of thousands of Americans died in the wake of an illegitimate attempt at secession predicated on the preservation of slavery. The Civil War amendments to the Constitution certainly improved the document, but they hardly erased a culture of violence and racism that made them a necessity.

The North won the Civil War, the South won Reconstruction. The explicit exemption of blacks from civil rights and political participation in the South as well as the emergence of a racist domestic terrorist organization are all evidence that wars and Constitutional amendments hardly erase cultures that took centuries to develop. A century after Robert E. Lee surrendered to General Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Court House, racists were murdering civil rights activists in the Jim Crow South. Thousands of black people had been lynched during those hundred years. Others were subjected to medical experiments. Segregation, bans on interracial marriage, and many other indignities were imposed by white-majority legislatures.

We can and should applaud the progress that the U.S. has made since its founding while accepting that there is much work to be done. Such work requires an honest look at history that treats the Founding Fathers and America’s founding documents as men and historical writings, not prophets and religious texts.

Although decades have passed since the civil rights movement American institutions continue to reflect America’s racist history. Law enforcement and criminal justice are perhaps the most prominent and obvious examples, but we shouldn’t ignore the impact racism has had on housing policy, education, and economic regulations. This history of course doesn’t imply that everyone who works in law enforcement, housing, and education or advocates for minimum wage increases is a racist, but it should be considered when discussing the ongoing impact of race relations on American society.

We should also consider modern moral hypocrisies and racial language. Today, many people who claim to support “liberty” protest the removal of statues of Confederate generals who fought to preserve slavery. More than 150 years after the end of the Civil War, a city worker in New Orleans wore body armor and a face covering while removing a statue of Confederate leader Jefferson Davis.

Rep. Mark Meadows (R‑NC), a member of the “Freedom Caucus,” won re-election despite saying that President Obama should be sent “back home to Kenya or wherever” (he has since disowned the comments). The whole Obama presidency is full of examples of thinly veiled racial language being used against the president and his family. Rep. Steve King (R‑IA) has used racist language and adorned his desk with a Confederate flag, which he displayed without any hint of irony alongside the American flag.

If initiatives like The 1619 Project can help Americans better understand their history and institutions then they should be applauded. I’ve yet to read the 1619 essay collection in full, and I’m sure that I’ll have some disagreements with some of its contributors. The essay on the link between slavery and the “brutality of American capitalism” looks ripe for educated criticism.

It’s important for an honest look at American institutions and history because the United States — unlike France and Greece — was founded on a set of principles. French and Greek identities have endured despite Greece and France being governed by a wide range of political regimes (republics, parliaments, monarchies, occupations, etc.). Yet there’s a sense in which American identity is tied to the political commitment outlined in the Declaration: a government tasked to securing rights endowed to all people.

I am bound to that commitment. I took an oath to the Constitution when I became an American citizen ten years ago. I did so gladly, knowing that the document and the men who ratified it were imperfect. But such imperfections didn’t dent my budding patriotism. Anyone with a family and friends knows that you can love something that isn’t perfect. My relationship with my country is like my relationship with anyone: it improves with increased honesty, reflection, and candor.