For updated data for this post based on the 6‑month delayed enforcement of the DACA repeal, please read this post.

On the campaign trail, Donald Trump claimed that he would cancel President Obama’s Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program, which allows young unauthorized immigrants—known as “Dreamers”—to live temporarily without fear of removal and work legally. To many people’s surprise (including mine), President Trump decided in January to maintain the program, issue renewals, and even allow new applicants into the program. But this will likely change soon.

Now several states led by Texas are attempting to force the president’s hand, requesting in a letter that he terminate the program by September 5 or face a lawsuit. Texas already successfully challenged President Obama’s 2014 attempt to expand DACA to a broader range of immigrants who came here as children and to create a new program for undocumented parents of U.S. citizens called DAPA. This makes a lawsuit very likely to succeed. Even if it were possible for the Trump administration to defend DACA legally, it is not clear that Attorney General Jeff Sessions would want to defend a policy that he has called constitutionally “very questionable.” In July, he refused to say he would defend it.

After the election, President Trump promised to “work something out” with the Dreamers, and in July, President Trump said that he alone will decide the future of DACA. But the politics just became much more difficult. Texas has essentially forced him to defend in court something that he had characterized as illegal amnesty on the campaign trail and something his biggest supporters hate. Moreover, Trump’s record with the courts is already making him appear inept, so he would likely not want to take the political hits when he could easily lose the case anyway.

If the president does rescind the DACA memorandum on September 5, the program will likely not disappear overnight. Rather, it will slowly wind down over the next two years.

Will Dreamers become priorities for removal?

DACA has three different aspects—deprioritization for removal, “deferred action,” and employment authorization. First, the DACA memo tells agents to prevent Dreamers who may be eligible for DACA “from being placed into removal proceedings or removed from the United States.” This provision deprioritizes their removal. Under new expansive enforcement priorities laid out in a February 20th memo from then-Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Secretary John Kelly, many DACA recipients would be targets for removal if Kelly’s successor rescinds the DACA memo. That’s because the Kelly memo creates “priorities” so expansive that they include nearly all unauthorized immigrants, while specifically rescinding all “conflicting” memos except for the DACA memo and the memo that expanded DACA and provided for the never-implemented DAPA program.

Like the DACA memo, the DAPA memo instructed Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) “to… prevent the further expenditure of enforcement resources with regard to these individuals” (i.e., undocumented parents of U.S. citizens and DACA children). After initially leaving it in place, Secretary Kelly rescinded the DAPA memo on June 15. Since then, DAPA-eligible immigrants have been eligible for removal, though it appears that ICE was already ignoring those provisions of the DAPA memo. If the DACA memo were rescinded without further DHS guidance, the same thing would happen to the Dreamers that it protects.

Texas and the other states threatening a lawsuit claim that their “request does not require the Secretary to alter the immigration enforcement priorities contained in his separate February 20, 2017 memorandum.” Nor does it “require the federal government to remove any alien.” But their letter simultaneously calls for the full rescission of the DACA memo, which would effectively alter the enforcement priorities in the February 20th memo and, absent any additional guidance, require the federal government to target Dreamers for removal.

Will Dreamers immediately lose deferred action?

The second aspect of DACA is “deferred action.” Deferred action provides protection against arrest by formalizing the decision not to remove them. If an ICE agent encounters a DACA recipient and enters their name into the agency’s database, they will find their status listed as “lawfully present.” DACA applicants submit a form I‑821D application to U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services with a $495 application fee, which covers the cost of a biometric background check. As of March 2017, 886,814 young immigrants had received an approved I‑797 Notice of Action form under DACA. Each I‑797 form is valid “unless terminated” for two years.

Figure 1: DACA Form I‑797 Notice of Action

Source: Imgur

If DHS cancels the DACA memo, it’s unclear whether the underlying deferred action grants would disappear. The threat letter from the states only requests that “the Executive Branch will not renew or issue any new DACA or Expanded DACA permits in the future.” The form itself states that it will “remain in effect for 2 years” unless “terminated.” Does this require an individualized termination for some violation of the program’s rules or would the termination of the program under which the form was issued suffice?

When Secretary Kelly rescinded the DAPA and Expanded DACA memo, he specifically stated that the memo would not “alter the remaining periods of deferred action under the Expanded DACA policy granted between the issuance of the November 20, 2014 Memorandum and the February 16, 2015 preliminary injunction order in the Texas litigation.” This refers to the 3‑year renewals issued to original DACA recipients who, both before the November 20th DAPA/Expanded DACA memo and after the injunction, received only 2‑year renewals. It is possible that the administration could duplicate this language in the DACA repeal itself.

Another option would be for the administration to leave it unclear, and if it does so, I suspect that individual ICE agents will end up making the determinations. According to the Feb. 20th Kelly memo, “the individual, case-by-case decisions of immigration officers” will have the final say over whether to make arrests.

Will Dreamers immediately lose employment authorization?

The final aspect of DACA is employment authorization. Every DACA recipient receives a 2‑year (or 3‑year, if they renewed in the period mentioned above) employment authorization document (EAD). DACA applicants must separately submit a Form I‑765 to receive an EAD. You can see an approved DACA EAD in Figure 2. The card contains a two-year validity period.

Figure 2: DACA-based Employment Authorization Document (EAD)

Source: WangLawOffice

Because employment authorization is dependent on a grant of deferred action, canceling part 2 of DACA would legally end part 3 as well. However, the memo that rescinded the DAPA/Expanded DACA memo also clarified that it does not “affect the validity of [3‑year] Employment Authorization Documents” granted before the injunction in the Texas case. Again, it’s possible that the administration will repeat this clarification in the DACA rescission. In any case, the EADs contain no indication that they were issued under DACA, and employers must accept any facially valid, non-expired ID when screening applicants for employment authorization. I have previously written about the Obama administration’s efforts to cancel certain DACA EADs and how difficult it was in my pre-inauguration post explaining how DACA could end. Given that this circumstance seems quite unlikely, I will not repeat myself here.

How DACA will end

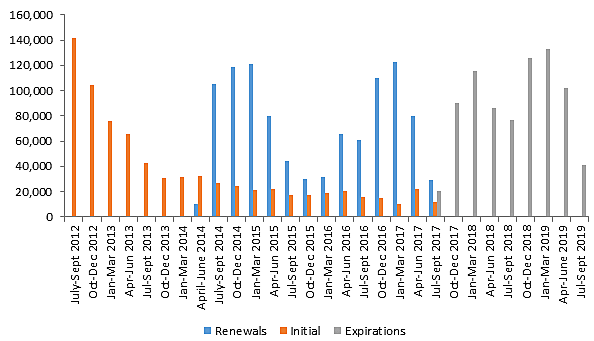

We know roughly how DACA will wind down because we know about when DHS approved the DACA applications. DHS publishes quarterly approval figures, and we know that it issued 108,000 3‑year renewals from November 20, 2014 to February 16, 2015. Figure 3 shows the approval schedule for DACA as well as the expected expiration schedule if DHS cancels the program on September 5, 2017, as requested in the states’ letter. As it shows, the DACA grants would expire over a two-year period ending in September 2019.

Figure 3: DACA Approvals—Initial and Renewals—and Projected Expirations

Source: USCIS Data Set: Form I‑821D Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals. April 2017 to September 2017 figures are not published yet and are projections based on the number of two-year renewals in those months in 2015.

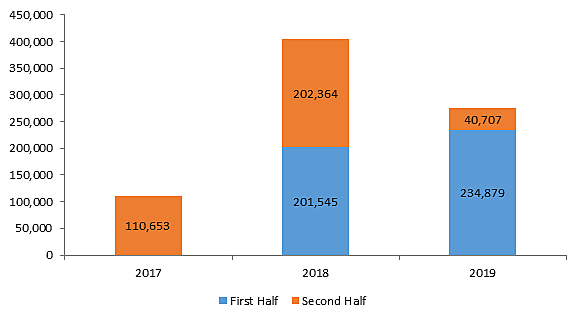

Unfortunately, the September 5 deadline will occur just before the expiration of the 108,000 three-year permits. Had President Obama issued only two-year renewals, these individuals would have already renewed their status a year ago, receiving an additional year of protection. Figure 4 provides the expirations by year. More than 60 percent of DACA recipients will still have protection and lawful employment through June 2018. More than a third will still be participating in DACA through January 2019—well over a year after the rescission of the DACA memo.

Figure 4: Projected DACA Expirations by Year

Source: Author’s calculation based on USCIS DACA Approval Figures.

The most likely scenario for DACA’s demise is that it will slowly wind down. President Trump has shown no willingness to move more aggressively against DACA recipients than is necessary, although certain ICE agents seem zealous about targeting them. If the president does determine that DACA should end, or the states receive an injunction against the program, Congress will need to act quickly as the permits expire. I suggest that they look seriously at the Recognizing America’s Children (RAC) Act, which would provide legal status and a pathway to citizenship for these immigrants brought to the U.S. as children.