America has a rich history of immigration—a longstanding tradition most Americans embrace. Earlier this year Gallup found that 77% of Americans say immigration is a “good thing” for the country. This belief crosses partisan lines: majorities of both Republicans (62%) and Democrats (89%) agree. However, despite overwhelming favorability toward immigration, only about a third of Americans want to increase it above current levels. Furthermore, when surveys offer respondents an opportunity to express if they think immigration has both benefits and costs to society, nearly half of Americans take it. A Washington Post/Schar School poll found that while 48% of Americans think that immigration has been “mainly good,” another 40% think it’s been both “equally good and bad” (and 11% said “mostly bad”). This shows that few Americans are outright anti-immigration. Rather, many have mixed emotions about the benefits and costs they associate with it.

Those skeptical of more immigration often raise concerns about jobs and wages, crime, and welfare when explaining their opposition. In response, immigration advocates argue that immigrants do not significantly reduce jobs or wages, increase crime, or disproportionately use welfare.

But can we always trust what people just explicitly tell us concerns them? Social psychology research indicates that we as human beings may often have trouble articulating why we think what we do—especially on emotionally charged topics. We often think up rationalizations for deeply felt gut instincts in real time. But sometimes those rationalizations don’t line up with what’s really motivating us. It’s not that people are being dishonest, but that often these motivations operate at a more subconscious level. When someone asks us to explain our beliefs, we may reach for explanations that ostensibly make sense to us in the moment, but may not be a clear reflection of what drives us.

In his book Whiteshift, political scientist Eric Kaufmann argues that ethnocultural concerns may be at the root of immigration restrictionism. If immigration concerns are more about culture and assimilation, then immigration advocates may find they are talking past people when they cite statistics about economic impact, jobs, crime, and welfare. It may also imply that emphasizing differences between Americans rather than what all Americans have in common, may not be particularly productive either.

Social science experiments can serve as a tool to better understand what’s truly motivating people. For this reason, we set out to conduct a series of experiments to investigate what improves public attitudes toward immigration. Today, we’ll report preliminary results from one new experiment, based on Kaufmann’s research.

We recruited 499 respondents on Amazon mTurk between December 11–27 and randomly assigned them to read one of three different newspaper clips. Afterwards, all respondents answered survey questions. Participants were told the researchers were investigating news recall and that they would be asked what they remembered about the article as well as a few other questions about their opinions. One treatment emphasized immigration and difference, the second one instead emphasized immigration and cultural assimilation, and the third (control) group was about…gardening!

We selected real news articles from the Washington Post and New York Times, shortened them, and then combined them with Kaufmann’s original treatments (that he fielded in the context of Brexit). (Full treatment text can be found in the Appendix below.)

Treatment 1: Difference Prime The first treatment group read a news clip adapted from a Washington Post article about new census data showing that by 2042 the United States will be a majority-minority country. It explains how this transformation began four decades ago with immigration and identifies several states that are already majority-minority. It concludes by telling readers that studies show that difference and diversity makes America more innovative and globally competitive, that diversity benefits everyone and is our nation’s strength.

Treatment 2: Assimilation Prime The second treatment group read a news article adapted from a New York Times’ Upshot article and Kaufmann’s original treatment. It tells respondents that as immigration has risen and fallen over time it hasn’t meaningfully changed American culture. It emphasizes how immigrants in the past and in the present have adopted American names, customs, and culture, and their children and grandchildren have political opinions like everyone else. Then it cites a new study of census forms (adapted from the Upshot) that shows over 2.5 million people who previously identified as Hispanic later came to identify as white. Similar to the first treatment, it concludes by telling readers that studies show immigration makes American business more innovative and globally competitive and benefits everyone.

Control Group: The control group read a third treatment: a gardening article from the New York Times. It offered helpful tips about how to maintain outdoor plants during the winter months.

After reading one of the three news clips, all three groups then took the same public opinion survey. (Demographics were collected in a short pre-treatment survey.) Our primary interest was the effect of reading the news articles on support for increasing immigration, measured by this question:

In your view, should immigration be increased, decreased, or kept at its present level?

- Increased a lot (5)

- Increased somewhat (4)

- Kept at present level (3)

- Decreased somewhat (2)

- Decreased a lot (1)

Results

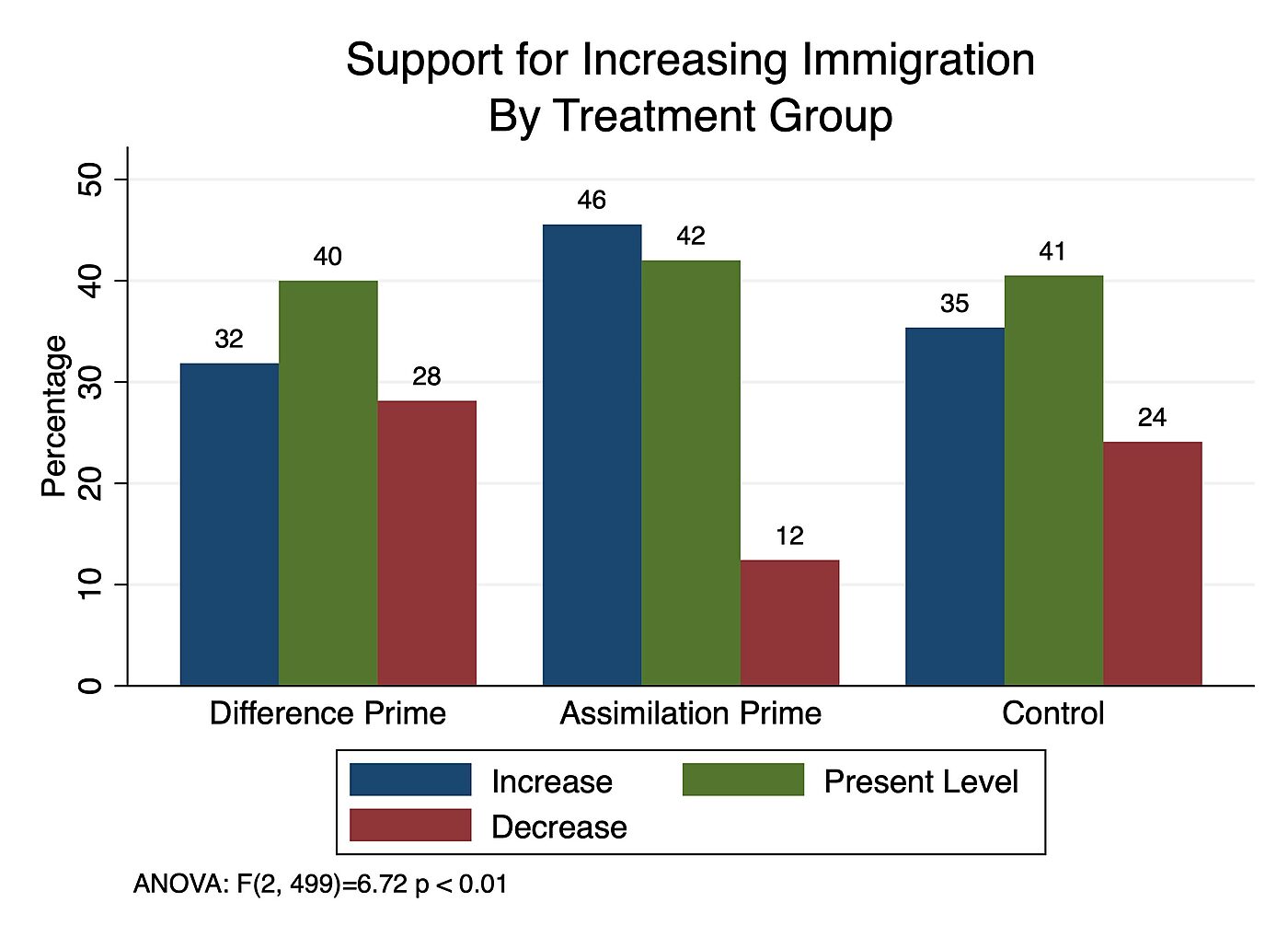

The Assimilation Prime had a strong and significant effect on immigration support. In the Assimilation group, 46% favored increasing immigration, compared to 35% in the control group—a treatment effect of 11 percentage points, statistically significant at the p < .01 level. Opposition to immigration in turn halved from 24% in the control group to 12% in the Assimilation group. If using the 5‑point immigration outcome measure (instead of net support/oppose), the Assimilation article had a treatment effect size of .36 scale points, or a third of a scale point, significant at the p < .001 level. Results from a comparison of means test indicate that higher support for immigration in the Assimilation group was statistically significant (t(362)=2.98, p = .01).

The Difference Prime did not significantly improve (or worsen) attitudes toward immigration. While 35% of respondents in the Control group wanted to increase immigration, so did 32% of respondents in the Difference group. Support for reducing immigration rose by 4 points from 24% in the Control group to 28% in the treatment group. Nevertheless, these differences are not statistically significant. Thus, telling people immigration is causing the country to become majority-minority does not meaningfully change attitudes toward immigration. This suggests that most Americans may not feel particularly threatened by demographic change.

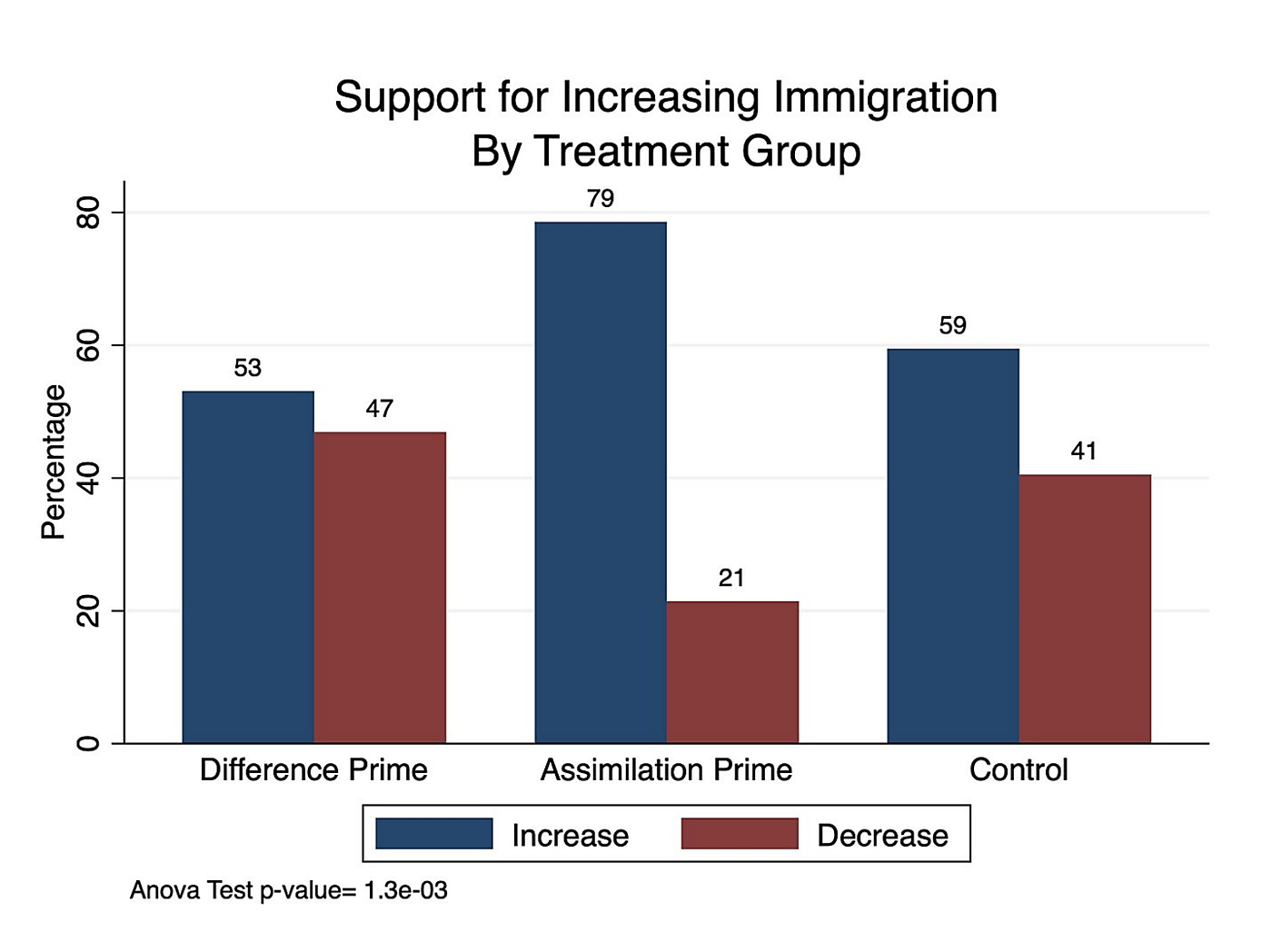

If we remove the respondents who wanted to keep immigration at present levels, the graphical display of effect sizes becomes clearer. Those in the Control group expressed similar views on immigration to those who read the Difference Prime. However, those who read the Assimilation Prime became more supportive and less opposed to immigration.

Impact on Democrats and Republicans

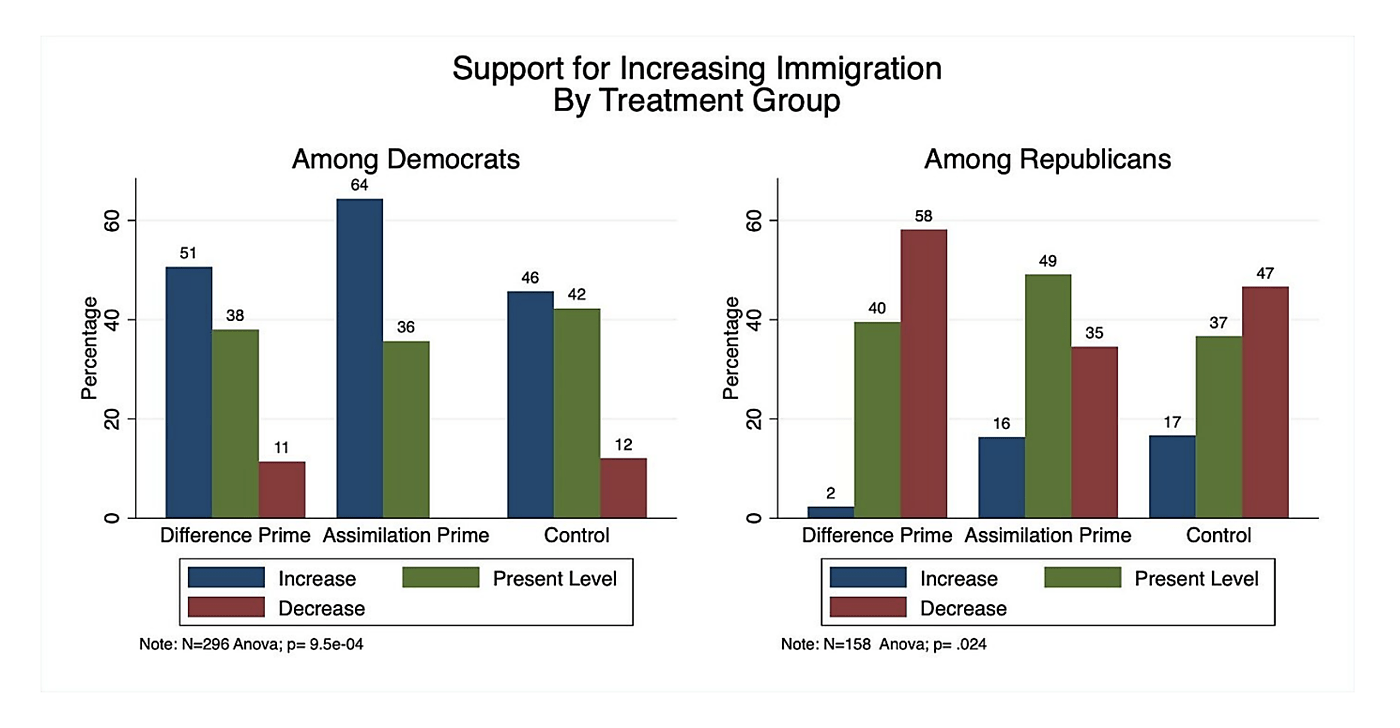

Next, we consider how Democrats (N=296) and Republicans (N=158) reacted to the treatments. The Assimilation Prime appeared to significantly impact Democrats while the Difference Prime appeared to significantly impact Republicans.

Among Democrats who read the Assimilation Prime, support for increasing immigration increased 18 points (from 46% to 64%), and support for decreasing immigration declined by 12 points (12% to 0%). Treatment effects were significant at the p < .001 level. Among Republicans in the Assimilation Prime, support for reducing immigration decreased by 12 points from 47% in the Control group to 35% in the Assimilation group. However, these differences were not statistically significant. It’s plausible that, with a larger sample size, the shift among Republicans would be significant, particularly among more moderate Republicans.

Turning to the Difference Prime, 51% of Democrats supported increasing immigration, compared to 46% in the control group, a 5‑point difference, but was not statistically significant. Republicans who read the Difference Prime appeared to backlash against immigration (significant at the p < .10 level). In the control group 47% of Republicans wanted to decrease immigration compared to 58% in the Difference Prime group—an 11-point effect. Seventeen percent (17%) of Republicans in the Control group favored increasing immigration compared to 2% in the Difference group, indicating a 15-point shift.

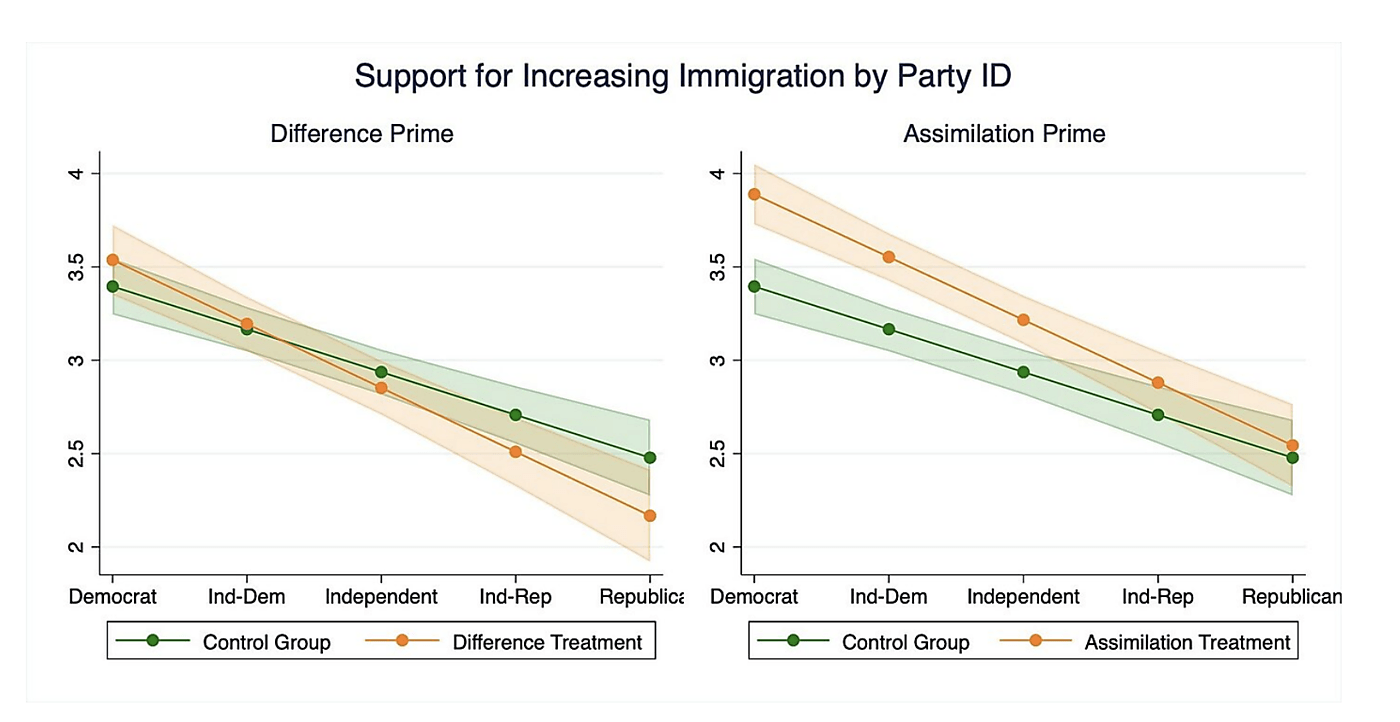

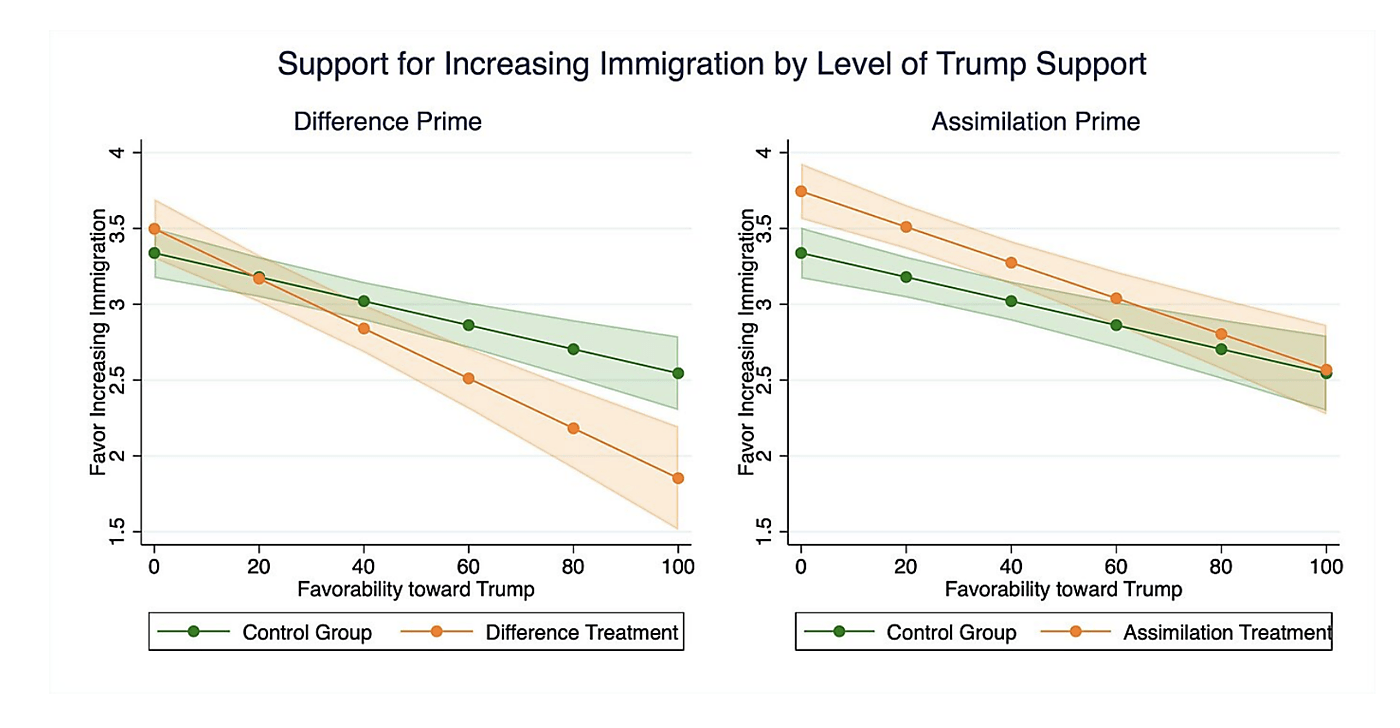

Measuring by Trump Support

These polarized reactions become more pronounced when comparing Trump supporters to opponents. Americans who rated Trump very highly on a scale of 0–100 (0=unfavorable to 100=favorable) and read the Difference Prime newspaper article became significantly more opposed to immigration. In contrast, Trump opponents reading the same article did not meaningfully change their minds on immigration (but may have leaned more in favor). In reverse, Trump opponents who read the Assimilation news article became significantly more likely to favor more immigration. Americans more favorable towards Trump were less persuaded by the Assimilation news clip.

Taking these results together indicate that anti-Trump Democrats become much more supportive of liberalized immigration when exposed to the Assimilation Prime. Moreover, this can be accomplished without eliciting backlash from their own side and may even mollify immigration skeptics on the Republican side.

Implications

These data indicate that convincing people that immigration will not change the American way of life to which they are attached may increase their comfort with increasing immigration. Messaging that focuses on diversity and its benefits may slightly increase support for immigration among Democrats, a group that is largely already in favor of immigration. But it risks eliciting a backlash from Republicans, especially Trump Republicans.

On the other hand, focusing more on the ways in which immigrants assimilate into American society sees a larger increase in support from Democrats without a backlash from Republicans. In fact, assimilation arguments may attenuate the anti-immigration sentiments of many Republicans. It might persuade moderate Republicans too. Altogether, these data show the benefits of emphasizing commonalities to promoting social harmony and increasing support for immigration.

In future experiments we hope to assess the impact of correcting misinformation about immigration’s effects on wages, crime, and welfare use on attitudes towards immigration.

Appendix: Treatment Text

Assimilation Prime:

Immigrants Assimilate into American Culture

Immigration has risen and fallen over time, but like the English language, American culture is not significantly impacted by foreign influence. Historically, a large share of the children of immigrants have adopted American names, customs and culture. Italian, German, Russian and Jewish immigrants largely melted into the white majority. Data show that trend continues today. Surveys show that the children and grandchildren of immigrants have opinions no different than other Americans.

According to the Pew Research Center, more than half of immigrants who marry in the U.S. marry a native-born American. Today, those of mixed race who share common ancestors with white Americans are growing faster than all other minority groups. A new study of census forms finds that 2.5 million people who once identified as Hispanic in 2010 now identify as white in 2020. The data suggests that Hispanics may assimilate as white Americans, like Italians or Irish, who in the past were not universally considered white. These projections suggest that as more immigrants come to identify as whites, whites will remain the majority for the foreseeable future.

Andrew Chorley, a sociologist at Johns Hopkins University explained, “Today’s minorities will be absorbed into the majority and foreign identities will fade, as they have in the past and for public figures with immigrant ancestors like Marco Rubio and Pete Buttigieg.” Ultimately, America shapes its immigrants, immigration doesn’t shape America.

Immigration won’t likely significantly change American culture and studies have shown it makes American business more innovative and globally competitive. Immigration benefits everyone.

Adapted from

Difference Prime:

Census: Minority babies are now majority in United States

For the first time in U.S. history, a majority (50.4%) of the nation’s babies are African American, Hispanic, or Asian American, according to new census figures. The latest estimates are a reflection of an immigration wave that began four decades ago. The transformation of the country’s racial and ethnic makeup has gathered steam as the white population grows collectively older, especially compared with Hispanics.

These data signal the dawn of an era in which whites no longer will be in the majority. The Census has forecast that whites will be outnumbered in the U.S. by 2042, and social scientists consider that current status among infants a harbinger of the change. “This is a watershed moment,” said Andrew Cherlin, a sociologist at Johns Hopkins University. “It shows us how multicultural we’ve become.”

Four states are already majority minority — California, Hawaii, New Mexico and Texas—and white Americans are a minority in 27 out of the 100 largest metropolitan areas. “The population is literally changing before us, with the youngest replacing the oldest,” Cherlin said. “This is the first tipping point. The kids are in the vanguard of the change that’s coming.”

We should embrace our diversity, studies have shown it makes America more innovative and globally competitive. Immigration benefits everyone. Diversity is our strength.

Adapted from

Control:

It’s (Nearly) Winter: Which Plants Can You Bring Inside?

It’s time to decide: Should you bother trying to save the plants you’ve been laboring over all summer or just buy replacements come spring? Rather than carrying annual pots indoors for winter, do this well before the first frost. First, pinch off any flowers or buds. The length of the cutting should average two to three inches.

Certain cuttings root readily in water, but a cell pack filled with potting soil is better. Mist regularly or put a plastic bag over the cell pack to make a mini-greenhouse. Fast-rooting cuttings like coleus and sweet potato vine can be potted up to larger containers.

When frost wilts the leaves and stems, cut the plant back to the ground and dig carefully. Lay in an airy spot out of the sun for a week. Put in a rodent-proof, frost-free space with a temperature of about 40 degrees, dark and not damp. You can treat some plants as houseplants. For others, store dormant plants in their pots. To do this, first cut off any flowers. Keep somewhere dry, dark and with a temperature of about 40 degrees.