From this report, it is clear that China’s financial system has adopted innovations at a much faster pace than the Western world. And if there is a defining characteristic of the Chinese system, it is its very erratic and repressive regulatory framework, which made me once call China a “spontaneous Frankenstein banking system”:

Financial regulation in China is quite a mess. China seems to be the world testing ground for some of the most ridiculous banking rules. With all their related unexpected consequences.

In an earlier post, I also highlighted that

China is an interesting case. Underneath its very tight government-controlled financial repression hide numerous financial experiments aimed at bypassing those very controls. The Chinese shadow banking system is now a well-known financial Frankenstein, with multiple asset management companies, wealth management products and other off-balance sheet entities providing around half the country’s credit volume. The more the government tries to regulate the system, the more financial innovation finds new workarounds and become increasingly more opaque.

We already knew that the Chinese financial system was completely distorted from years of regulatory repression and crony capitalism, as a whole new report on finance in China by The Economist demonstrates (see the editorial here, and the report starting here). Echoing my worries, The Economist calls for China to “free up” its “financial jungle.” Citi’s and The Economist’s reports now allow us to quantify the effects of those distortions. Indeed, China leads the world in fintech and digital disruption in general; it has some of the largest fintech firms and, as Citi said, it is now “past the tipping point.”

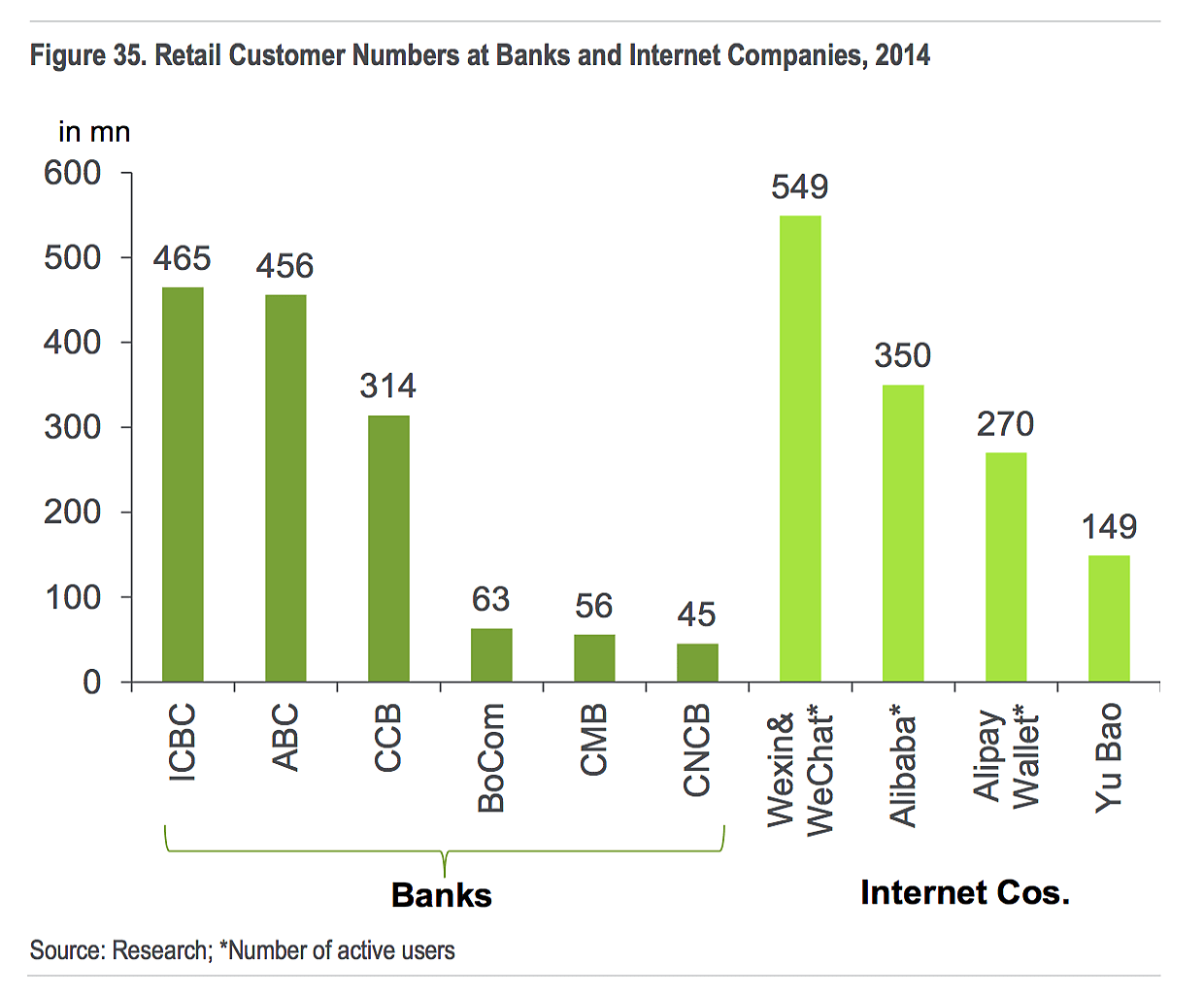

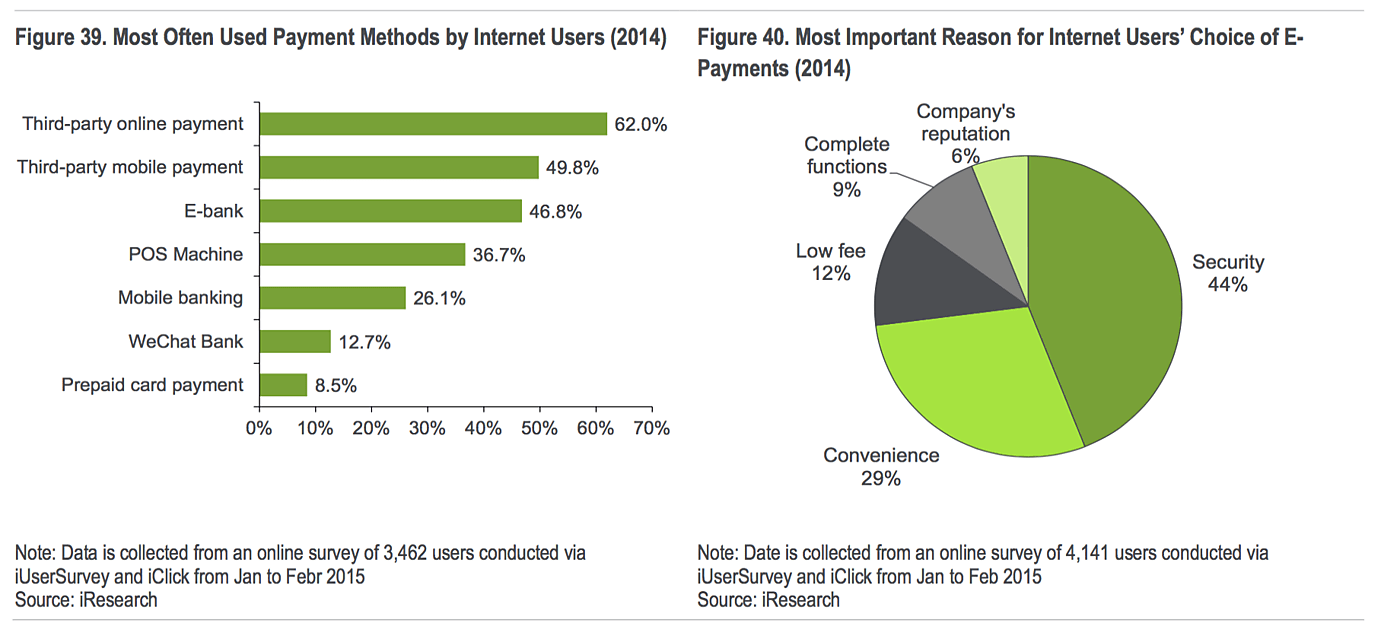

While its very large e‑commerce has been a strong driver of the rise of alternative payment providers in the country, Citi points at a number of other factors that have facilitated the rise of those third-party payment companies, among which an under-developed banking system viewed by the public as quite unreliable (unsurprising given how tightly controlled banking is in China, which has stifled customer-oriented innovation), and “relaxed regulation.” Citi points out that Chinese regulators have now proposed new tightened rules for the payment sector, so brace yourself for further innovations in this space. For now, Alipay handles more than three times the volume of transaction that Paypal does, and payment firms have more retail customers than banks have and are now expanding into offline payments.

China also has the largest P2P lending market in the world, four times bigger than that of the US. Citi analysts forecast that P2P loans are going to represent a sizeable 9% of total retail lending in China by 2018.

The driver of this growth is, typically, mostly regulatory constraints on traditional banking that triggered regulatory arbitrage:

P2P lending platforms target segments that are unserved or under-served by existing banking system such as consumer credit and small and micro business lending. Traditional banks are not particularly good at serving this customer segments due to tougher Know Your Client/Anti-Money Laundering (KYC/AML) requirements as well as tightened lending standard post global financial crisis.

And one would add that capital requirements on certain category of customers (such as SMEs) play a large role here too, as I keep pointing out on this blog (see at the end of this post). The same reasons are behind the development of such lending platforms in Europe and the US. And indeed, as Citi writes:

According to China MSME Finance Report 2014 by Mintai Institute of Finance and Banking, almost 80% of SMEs were not served by the banks. The explosive growth in the P2P lending has met the needs of SMEs which cannot get formal financing.

And:

Chinese banks are under tight regulations such as reserve requirement, loan-to-deposit ratios (LDR), KYC, AML, and so on. There was however little regulations for the P2P lending sector. There is also no capital requirement.

Furthermore, Chinese monetary repression is also a driver, as P2P lending allows savers to earn higher returns. Here again, Chinese regulators are looking at ways to scrutinize and more tightly control the sector.

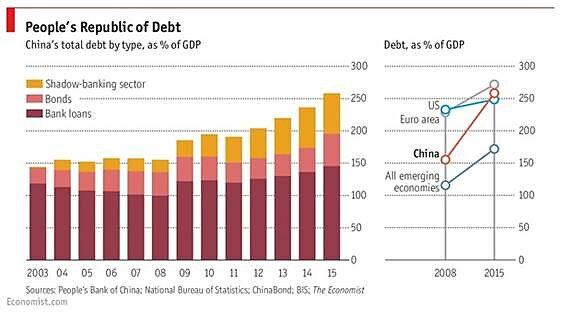

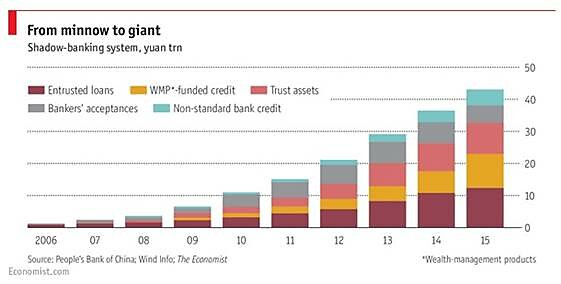

What are the effects of all this? As The Economist points out, China’s shadow banking sector is the largest and possibly the fastest growing in the world:

There is a fundamental difference between the Chinese banking system and the Western one however. Chinese banks, despite being extremely large, have historically had no ability to grow outside of the Communist party’s grip and no ability to adapt to consumer demand as a result. Citi points out that there were only 8.1 bank branches per 100,000 adults in China, vs. around 30 in the Eurozone and the US. With little banking presence, fintech firms have found it easy to rapidly grow.

Yet, developed economies do have a lesson to learn from the Chinese experience. The more regulatory constraints are put in place on banks, the more innovative ways around them will spontaneously emerge and the more complex and opaque (“Frankenstein-like”) the financial system will become. And sadly, it looks like Europe and the US have decided to follow China’s footsteps.

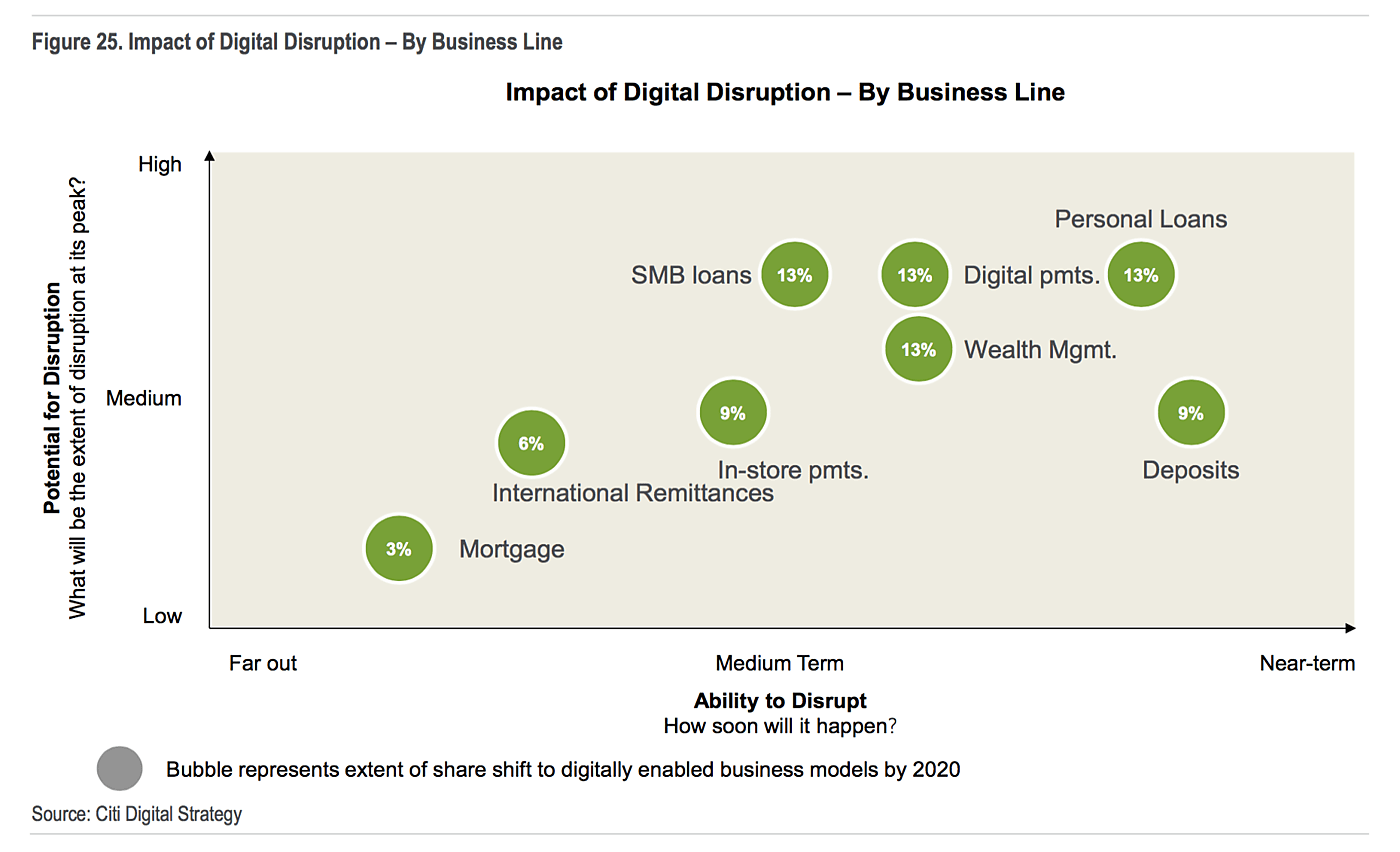

PS: The following chart is revealing. Most of the financial products that are at most risk of disruption (SME and personal loans, deposits…) are also those that are the most affected by regulatory requirements and low interest rates.

PPS: A very good introduction to the Chinese financial mess is Walter’s and Howie’s Red Capitalism. However the book was “only” updated in 2012, and plenty has happened since then, in particular in the fintech portion of China’s shadow banking sector.

[This article originally appeared on Spontaneous Finance]

Disclaimer

This post was originally published at Alt‑M.org. The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Cato Institute. Any views or opinions are not intended to malign, defame, or insult any group, club, organization, company, or individual.

All content provided on this blog is for informational purposes only. The Cato Institute makes no representations as to the accuracy or completeness of any information on this site or found by following any link on this site. Cato Institute, as a publisher of this article, shall not be liable for any misrepresentations, errors or omissions in this content nor for the unavailability of this information. By reading this article and/or using the content, you agree that Cato Institute shall not be liable for any losses, injuries, or damages from the display or use of this content.