“Trump’s tax cuts are rocketing us into the debt ceiling,” wrote Catherine Rampell in The Washington Post on February 1, because “withholding from employee paychecks will drop starting no later than mid-February. Individual income tax revenue will therefore be about $10 billion to $15 billion less per month than the CBO previously estimated.” The suggestion that the debt crisis could be blamed on a mere $10–15 billion cut in monthly withholding got a Twitter shout-out from budget hawk Stan Collender, who must know that errors in monthly budget estimates are commonly larger than that.

This was followed two days later by Heather Long’s extremely misleading Washington Post story, “The U.S. Government Is Set To Borrow Nearly $1 Trillion This Year, an 84 Percent Jump from Last Year.” The article goes on to say, “Treasury mainly attributed the [$436 billion debt] increase to the ‘fiscal outlook.’ The Congressional Budget Office was blunter. In a report this week, the CBO said tax receipts are going to be lower because of the new tax law.” According to that link to another Post story, “CBO said that the tax law is expected to lower tax receipts by $10 billion to $15 billion per month. Even though the tax cut law went into effect January 1, the large drop in tax receipts didn’t kick in yet because companies won’t start using new withholding tables until sometime in February.” Fiscal 2018 began last October, so lower withholding tax can affect no more than 8 of the remaining months. Contrary to the Rampell-Long theory, the CBO’s revenue loss of $80–120 billion can’t explain her alleged $436 billion increase in Treasury borrowing.”

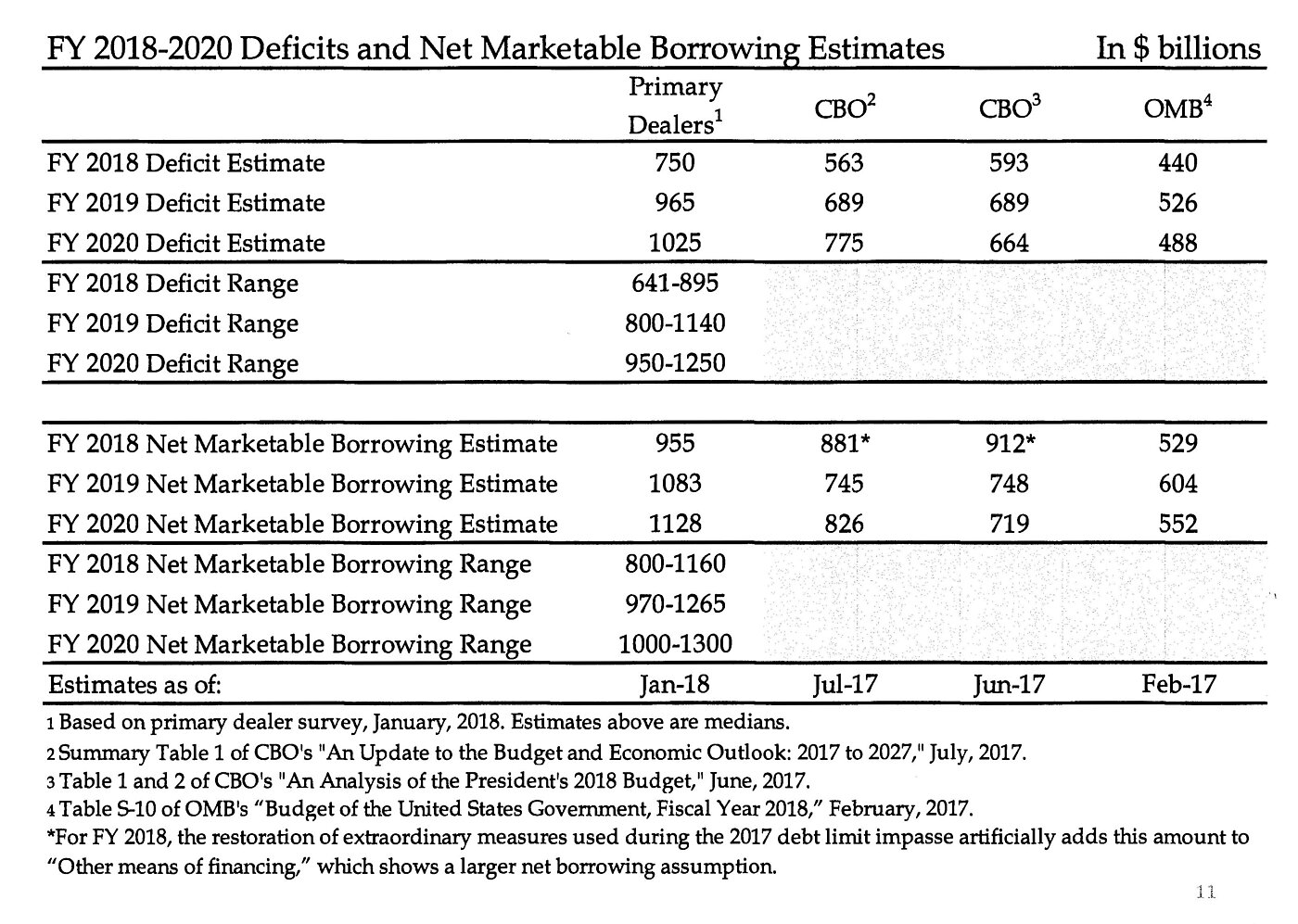

Where did all that added debt come from? What Ms. Long initially called “the exact” figure of $955 billion is later explained as “determined from a survey of bond market participants.” Asking about 23 bond dealers to guess Treasury “net marketable borrowing” is far from an official estimate, and it isn’t a measure of the deficit.

The first Table shows that OMB and CBO estimates show the FY 2018 deficit falling by 11–34% from the $66 billion in FY 2017. The median guesstimate in the last New York Fed’s email Survey of Primary Dealers, by contrast, is a FY2018 deficit of $750 billion. It’s a very small sample of non-expert opinion, and we don’t know the range and variance of forecasts or the Survey’s forecasting record.

Note well, however, that the Washington Post writer’s unexplained $955 billion private estimate of net borrowing is much larger than the 23 Primary Dealers’ wildcard estimate of a $750 billion deficit. Why? The reason is explained in the Table’s Footnote 5: “For FY2018, the restoration of extraordinary measures used during the 2017 debt limit impasse artificially adds to the ‘other means of financing’ which shows a larger net borrowing assumption.” Extraordinary measures include such things such as suspending debt issuance for civil service and USPS retirement benefits and redeeming certain securities instead of issuing new ones.

In case anyone missed the connection Rampell and Long were insinuating–that tax cuts nearly doubled FY2018 borrowing–an Axios summary of Long’s report was headlined: “After Tax Cuts, U.S. Borrowing To Spike 84% This Year to Nearly $1 Trillion.”

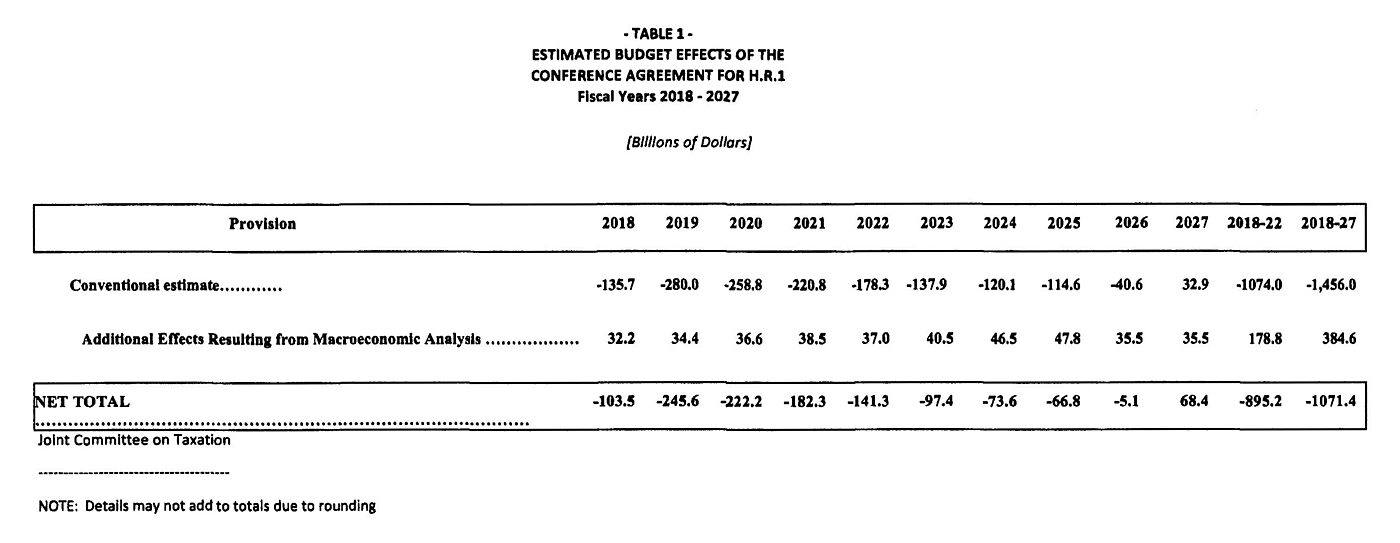

Aside from the mathematical implausibility of blaming an alleged $436 billion increase in borrowing on a JCT-estimated $103.5 billion tax cut (see the second Table), it was inexcusable for the Washington Post to publish the bizarre $955 billion net borrowing estimate without divulging that (1) it was a median estimate from an email survey of 23 bond dealers, and that (2) that dubious unofficial FY2018 estimate was also artificially inflated by “extraordinary measures” taken during debt limit impasse.