Over the past month, U.S. forces have struck possible terrorist targets in the vast unpoliced region of western Pakistan known as the Federally Administered Tribal Areas, or FATA. Many of the attacks have been conducted with missiles fired from unmanned planes, and at least one with Special Forces ground troops. These strikes followed a string of operations the Pakistani military launched in August under increased U.S. pressure – attacks in FATA’s Bajaur Agency killed almost 70 militants, wounded 60 others, and displaced 200,000 refugees.

While its true that unilateral missile strikes and commando raids can successfully extinguish high-value targets, the collateral damage unleashed by such attacks may only be adding more fuel to violent religious extremism in this nuclear-armed Muslim-majority country.

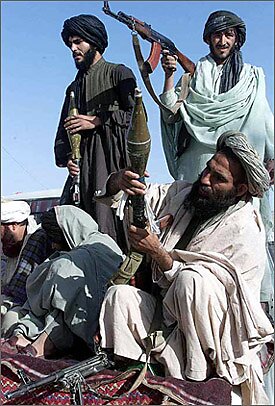

FATA has long remained a mystery to the outside world. The region’s deep ravines and isolated valleys – much of which can support only foot traffic or pack animals – is inhabited by fiercely independent Pashtun tribes who adhere to the pre-Islamic tribal code of Pashtunwali. Social values include hospitality (melmastiya), loyalty (wafa), and honor (nang). But one other closely held tribal precept is badal, the Pashto word for taking revenge.

During a visit last month to the frontier region, I spoke with local tribesmen from the South Waziristan Agency. They noted that the collateral damage unleashed by U.S. and Pakistani missile strikes has ripple effects throughout tribal society, provoking a backlash that has inflamed local tribes and triggered collective armed action throughout the region.

U.S. policymakers point to the successful killing of top Al Qaeda militants, such as Abu Laith al-Libi last January and chemical weapons expert Abu Khabab al-Masri in July, as effectively vindicating the military approach. But the fallout from U.S. missile strikes proves strategically problematic for three reasons.

First, missile strikes undermine the authority of sitting Pakistani leaders and further strain already shaky U.S.-Pakistan relations. The August 19th resignation of Pervez Musharraf shows how Washington’s embrace can prove a political liability for “war on terror” allies. It’s also one reason why Pakistan’s new president, Asif Ali Zardari, is reviled by many Pakistanis—among other things—for his pro-American stance, while opposition leader Nawaz Sharif, has seen his popularity soar.

Second, military strikes encourage insurgents to lash out against the government of Pakistan, further eroding U.S. standing in the region. Militants routinely attack law enforcement officials, military outposts and political leaders. Suicide bombers were virtually unheard-of in Pakistan before 9/11, but now strike with increasing frequency and in large urban centers, such as Peshawar, Karachi and Islamabad. I spoke with over a dozen Pakistani government officials in Karachi, Lahore and Islamabad, and it is clear they take the insurgent threat seriously. And despite Washington’s repeated accusations of Islamabad’s duplicity in aiding terrorists, the Pakistani army has lost over a thousand soldiers in direct confrontation with insurgents. Further inflaming internal tensions, the South Waziri tribesmen I spoke to perceive that Pakistani action in the tribal areas are being conducted at the behest of Washington. Any plan to contain the spreading insurgency must originate with the civilian leadership in Islamabad.

The final, and most important, reason to be circumspect about escalating military force in the tribal areas is that it will almost certainly fail. The clans of Pashtun tribes straddling the Afghan-Pakistan border have endured thousands of years of foreign invasion. Time and again, Persian, Greek, Turk, Mughal, British and Soviet invaders have learned these peoples to be virtually unconquerable.

It’s clear that the insurgency cannot be eliminated militarily. But Islamabad’s recent course of cutting peace deals with militants has proved equally ineffective. The deals reduced the Pakistani army’s presence in some of the tribal areas, but such moves merely allowed radicals to make further territorial gains.

A better strategy would be to employ low-level “clear and hold” operations, in which small numbers of U.S. Special Forces and Pakistan’s Special Services Group (SSG) perform limited ground and air operations in and around FATA. Although such a limited presence is less than ideal for a region as expansive FATA, an area equivalent in size to Vermont, a heavier combat presence risks provoking a more hostile response. A limited presence with highly trained forces would be better positioned to root out militant safe havens and deny insurgents a base from which to attack U.S.-led NATO operations in neighboring Afghanistan.

Predator-drone attacks and major military campaigns ignore the history, character and ethos of the tribal regions. The struggle for Pakistan’s border is best waged through as light a military footprint as possible. Blunt force is an antidote that will prove worse than the disease.