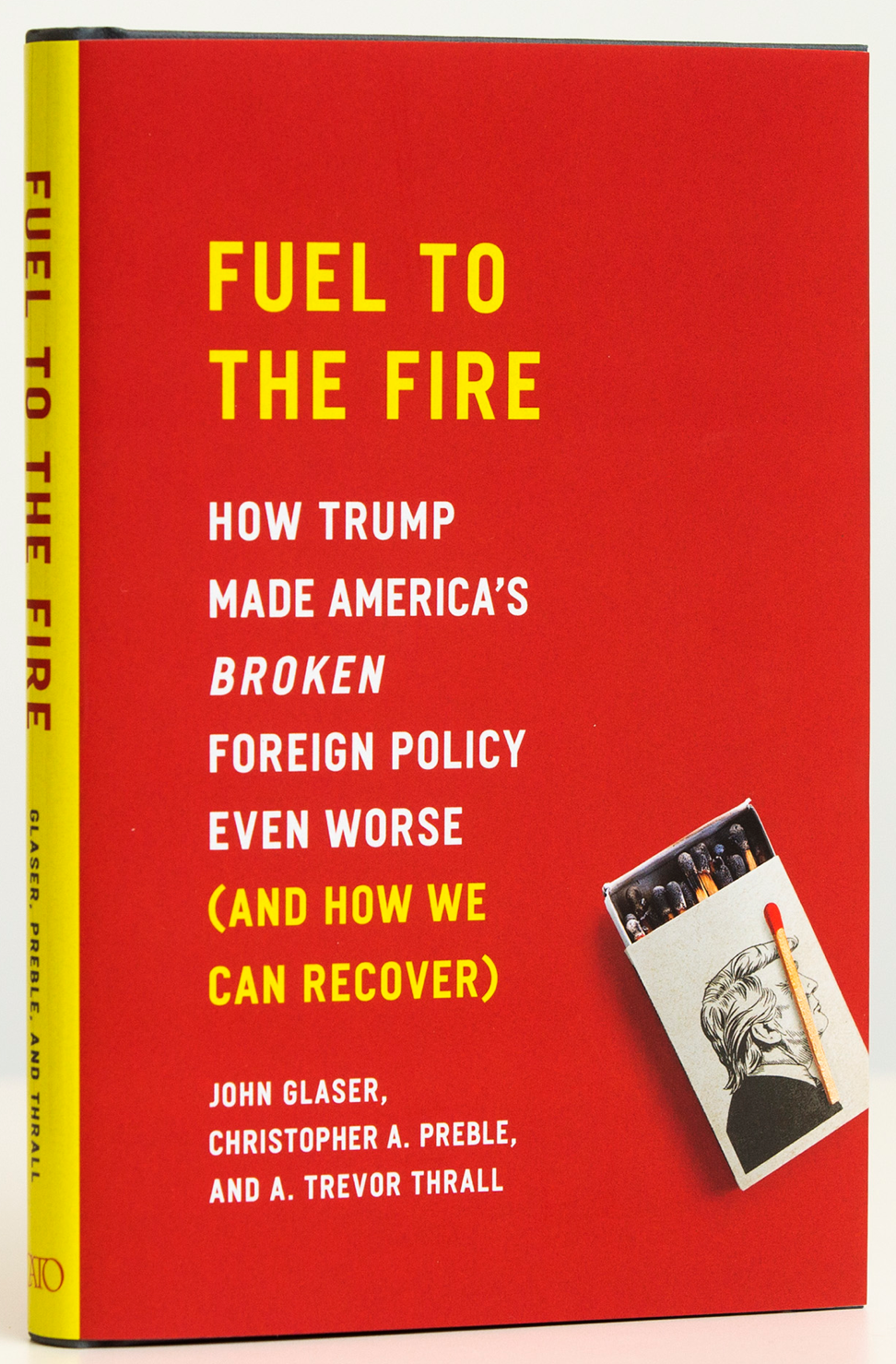

In our book, Fuel to the Fire, John Glaser, A. Trevor Thrall, and I lament how "the fear of a rising China" was fast becoming "the most popular candidate for a new guiding principle in U.S. foreign policy." Indeed, in an era of hyper partisanship, it is notable how the idea of a new Cold War draws so many advocates on both the left and right.

There are some notable exceptions, to be sure. In July, a distinguished group of China scholars and U.S. foreign policy experts penned an open letter explaining "China is not an enemy." And, earlier this week, the just-launched Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft released its very first policy brief. Written by the esteemed American diplomat Chas W. Freeman, Jr., it warns that the United States is making a mistake by embarking on "a new era of 'great power competition'" and advises instead that Washington and Beijing cooperate to tackle "planetwide problems."

In this same vein, among skeptics of the fearmongering surrounding China, Fareed Zakaria's essay in Foreign Affairs is likely to receive considerable attention. In it, Zakaria assails many of the leading arguments for why Americans (and the rest of the world) should be panicked by China's growing wealth and power.

Importantly, Zakaria echoes Patrick Porter's observations in a Cato paper (and forthcoming book) concerning the so-called liberal international order and China's supposedly unique threat to that order. Both writers are anxious to correct the myths and misconceptions surrounding international relations before China's emergence. "It is...worth remembering," Zakaria writes, "that the liberal international order was never as liberal, as international, or as orderly as it is now nostalgically described."

"A more realistic image," he goes on:

is that of a nascent liberal international order, marred from the start by exceptions, discord, and fragility. The United States, for its part, often operated outside the rules of this order, making frequent military interventions with or without UN approval; in the years between 1947 and 1989, when the United States was supposedly building up the liberal international order, it attempted regime change around the world 72 times. It reserved the same right in the economic realm, engaging in protectionism even as it railed against more modest measures adopted by other countries.

Nevertheless, on the whole, there is relative peace and stability in the world, and trade -- despite recent "backsliding on some measures of globalization" -- is still more free than it was a generation ago. In that context, Zakaria writes, "China hardly qualifies as a mortal danger to this imperfect order." It "has acted in ways that are interventionist, mercantilist, and unilateral—but often far less so than other great powers."

In sum, "The nature of the challenge from China is different from and far more complex than what the new alarmism portrays. On the single most important foreign policy issue of the next several decades, the United States is setting itself up for an expensive failure."

He's right. A course correction is needed. This essay could help. You can find it here.