The Democrats have moved their huge tax-and-spend reconciliation bill through the House, and it now heads to the Senate. The bill includes large tax increases on businesses, investment, and high-earning individuals.

The bill also includes $80 billion of increased funding for the Internal Revenue Service (IRS). The IRS workforce would double, with the focus on expanded tax enforcement. The aim is to raise revenues by reducing the tax gap, which is the amount of taxes legally owed but not paid. I argue here and here that more aggressive IRS enforcement would impose substantial costs on Americans in terms of paperwork, lawyer fees, and civil liberties.

Democrats argue that more IRS enforcement is needed to combat rampant tax cheating. But international studies show that the United States has a fairly low tax gap and small shadow economy compared to other countries. In the studies below, the shadow economy generally refers to otherwise legal activities that are outside the government’s tax and regulatory grasp. The tax gap is the amount of revenue that would be raised if the shadow economy were taxed.

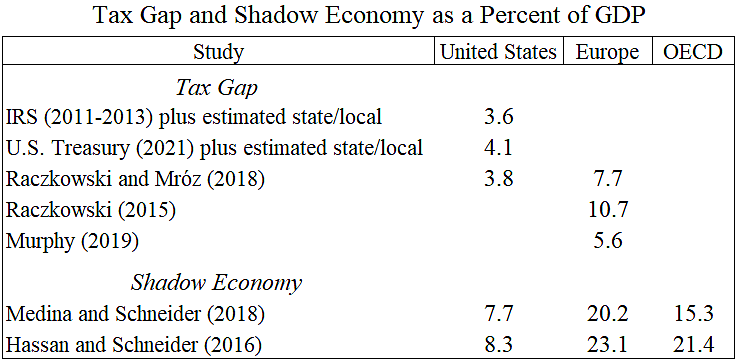

The table shows estimates of tax gaps and shadow economies as a percent of gross domestic product (GDP) for the United States and the averages for countries in the European Union (EU) and Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). The estimates show that the U.S. tax gap and shadow economy are generally smaller than the country averages.

The last detailed IRS estimate put the net federal tax gap at 2.3 percent of GDP for 2011–2013. The Biden Treasury estimated that the 2019 net federal tax gap was 2.6 percent of GDP. To get the total U.S. tax gap shown in the table, I added estimated state-local tax gaps based on the ratio of total state-local to federal tax revenues (0.56 to 1).

In a 2018 study, Konrad Raczkowski and Bogdan Mroz estimated tax gaps for 35 countries including 28 EU countries and the United States. They put the U.S. gap at 3.8 percent and the EU gap at 7.7 percent.

In a 2015 study, Raczkowski estimated that the tax gap for 28 EU countries was 10.7 percent.

In a 2019 study, Richard Murphy estimated that the tax gap for 28 EU countries was 5.6 percent. Murphy says that his estimate is likely understated.

The EU tax gap may be higher than the U.S. tax gap partly because the overall EU tax burden is higher. We can adjust the EU tax gap estimates downward using the ratio of U.S. taxes-to-GDP to EU taxes-to-GDP of 0.64. The adjusted EU tax gap estimates are 4.9 percent for Raczkowski-Mroz, 6.8 percent for Raczkowski, and 3.6 percent for Murphy. These figures are still similar or higher than the U.S. tax gap.

In a 2018 study, Leandro Medina and Friedrich Schneider estimated the size of shadow economies for 158 countries. The U.S. shadow economy is the second smallest of all countries. Over the 2010 to 2015 period, the U.S. shadow economy at 7.7 percent of GDP is only a fraction the size of Europe’s at 20.2 percent and the OECD’s at 15.3 percent.

In a 2016 study, Mai Hassan and Friedrich Schneider estimated shadow economies for 157 countries. For 2013, the United States at 8.3 percent is much smaller than Europe at 23.1 percent and the OECD at 21.4 percent.

Tax gap studies find that higher tax burdens induce more tax cheating. Hassan and Schneider note: “It is widely accepted in the literature that the most important cause leading to the proliferation of the shadow economy is the tax burden. The higher the overall tax burden, the stronger are the incentives to operate informally in order to avoid paying the taxes.” Thus, Democratic plans to increase tax burdens would likely expand the U.S. shadow economy and related tax gap.

Also, some studies, such as this one, point out that tax gap estimates overstate revenue that would be gained from greater enforcement if they do not include behavioral responses. If the IRS were to squeeze more money out of small businesses, for example, some businesses would reduce hiring and investment or even close their doors. Those responses would reduce revenues raised. Tax cheating is unethical, but higher taxes would damage the private economy whether they stem from law changes or IRS crackdowns.

A final note is that all the estimates cited here should be considered rough. Tax gap estimates are “shades of gray,” as discussed in an excellent new paper by Daniel Hemel, Janet Holtzblatt, and Steve Rosenthal. The authors describe reasons why the actual federal tax gap may be either higher or lower than estimates by the IRS and the U.S. Treasury.

In sum, the U.S. tax gap and shadow economy appear to be relatively small. In my view, reducing the tax gap by giving the IRS more enforcement power is not worth the likely damage to the economy and our civil liberties.

However, policymakers should pursue reforms to reduce the tax gap. They should provide funding and oversight for the IRS to improve its computer systems, employee training, and help services to reduce errors. They should repeal complex and fraud‐ridden provisions such as the low-income housing tax credit. They should repeal provisions that impose excessive administrative costs such as the earned income tax credit. And finally, policymakers should not add special‐interest breaks to the tax code, as the Democrats are proposing in their reconciliation legislation.