Well before Barack Obama was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, Americans were speculating on whether his ascendancy to the highest office in the land would help to improve the United States’ tarnished reputation in the world.

The early indications were encouraging, but largely anecdotal. The Pew Research Center provided data from surveys taken in May and June, and found a mixed picture: attitudes toward the United States were most improved in Western Europe, East Asia, and Africa (Nigeria and Kenya), but barely changed in the several predominantly Muslim countries polled, including U.S. allies Turkey and Pakistan.

The more relevant question is whether we should care. International relations is not a popularity contest. In the classical formulation, nation-states pursue policies that they believe will advance their interests. Sometimes these policies backfire. Sometimes they fail. But, all other factors being equal, we should assume that policies are directed from within, and not much influenced by without.

A recent study published by the American Political Science Association makes a reasonably convincing case that Americans should care about U.S. “standing” not purely for the sake of feeling good about ourselves, but also because improved standing is likely to contribute to more effective foreign policy. “Diminished standing may make it harder for the United States to get things done in world politics,” the report explains. In this context, the report continues, we should “think of standing … as the foreign-policy equivalent of ‘political capital.’ ” If we have a stored reserve of such capital, we can deploy this to mobilize international support. At a minimum, this will convince other countries to go along with us; in ideal cases, we might obtain their active support.

The report was commissioned by the outgoing APSA president, Peter J. Katzenstein of Cornell University, and the task force was chaired by Jeffrey Legro of the University of Virginia, and included a number of eminent scholars. [The full report is available here, a shorter public version was made available here, and Katzenstein and Legro summarized the findings in a recent article at Foreign Policy.com.]

For the sake of argument, I will concede that America’s reputation is a factor in the extent to which other countries support or oppose our policies, and therefore that it is worthwhile to attempt to bolster our reputation. But the report inadvertently shows that, in practice, even concerted effort by policymakers and opinion leaders to improve U.S. standing is likely to fail, largely because of deep contradictions between what others expect of Uncle Sam, and what Americans expect from our government and from others.

Generally speaking, non-Americans like the United States playing the role of world policeman — provided we do the job well. If the U.S. military deters aggression against small or weak countries, those countries won’t have to devote resources to defending themselves. Oppressed people often welcome U.S. pressure on the autocratic regimes that are oppressing them; some disenfranchised people welcome U.S. government efforts to give them some say in how they are governed, and by whom.

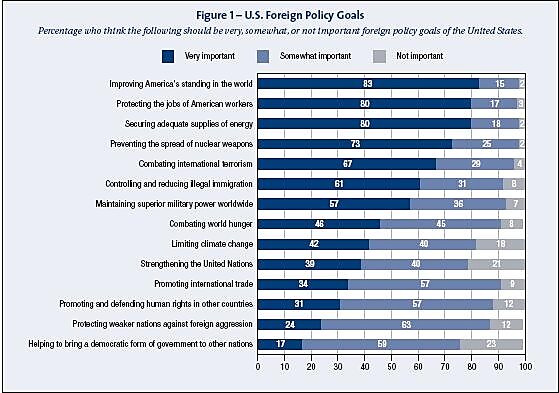

If the opinions of non-Americans were decisive in the formulation of U.S. policies, then we might be able to do all of these things. But they are not. In a list of 14 foreign policy goals polled by the Chicago Council on Global Affairs, Americans rank “Promoting and defending human rights in other countries” and “Protecting weaker nations against foreign aggression” 12th and 13th, respectively. As far as democracy promotion goes, that falls dead last on the list; a mere 17 percent of respondents thought this a “very important” goal for the U.S. government.

Despite public skepticism toward these goals here in the United States, non-Americans can be forgiven for believing that the U.S. government exists to do such things for them. After all, the notion that the United States should be the primary provider of global public goods has guided U.S. foreign policy for decades, and almost always in the face of strong opposition to such philanthropic impulses.

As I explain at length in my book The Power Problem, the disconnect between what the public wants, and what the policymakers give them, is deliberate and by design. Most of the people in Washington dismiss public attitudes as misinformed at best and isolationist at worst. But while I agree that we should not conduct our foreign policy on the basis of polls and focus groups, in the grand scheme, the hand-waving and misdirection that our leaders have employed since the end of the Cold War to conceal and distort the true costs of our current grand strategy is, well, unseemly.

Michael Lind has a better word for it: “Nothing could be more repugnant to America’s traditions as a democratic republic,” he writes in The American Way of Strategy, “than a grand strategy that can be sustained only if the very existence of the strategy is kept secret from the American people by their elected and appointed leaders” (my emphasis).

I wholeheartedly agree. In a country that presumes some measure of popular consent, the current pattern is repugnant.

So what does this mean for improving American standing? If the rest of the world wants the United States to be the world’s cop, social worker, and election monitor, but Americans expect our government of limited, enumerated powers to do these things only when U.S. national interests are at stake (and they rarely are), is this the counsel of despair?

Not necessarily. There is another way in which the United States could improve its international standing without having to go out of its way to convince others of our good intentions, and without systematically concealing from the American people the true object of our foreign policies.

As formulated by the APSA task force, “standing” consists of two elements, “credibility” — “the U.S. government’s ability to do what it says it is going to do” — and “esteem” — which “referes to America’s stature, or what America is perceived to ‘stand for.’ ” The right-leaning members of the academy, including George Washington University professor Henry Nau and Stanford’s Stephen Krasner, who submitted a spirited dissent from the report, question the importance of esteem. Tod Lindberg echoed these sentiments in comments at the National Press Club several weeks ago, at the time of the report’s public release.

I think it goes too far to say that esteem is essentially irrelevant, but I agree that credibility is the more important of the two. As such, it is crucial to fashion policies that are consistent with the wishes of the American people, and that can be sustained in the face of difficult circumstances and potentially high costs.

This means we need a new grand strategy. We could drop the revolutionary impulse behind our foreign policies, declaring ourselves content with the international status quo, and therefore not an imminent threat to any other country or people that respects our rights and liberties. We could likewise disavow any attempt to overthrow the established social order in foreign lands, and reaffirm our respect for sovereignty under international law. Finally, and most importantly, we could reestablish our international reputation by keeping our promises, and that would begin by not making promises that we can’t — and have no intention to — keep.

I will have more to say about that last point at a discussion next month hosted by the Institute on Global Conflict and Cooperation at the University of California’s Washington Center. To learn more, visit their website.

(C/P from the Partnership for Secure America’s Across the Aisle)