This week in New York, President Obama is hosting a summit on refugees with other governments with the goal of doubling refugee resettlement internationally. The summit will come a week after the president announced that the United States will plan to accept 110,000 refugees in fiscal year (FY) 2017, which begins in October. While this is 25,000 more than this year’s target, it is still much less than the share of the international displaced population that the country has historically taken.

If the next administration follows through on the president’s plans, 2017 would see the largest number of refugees accepted since 1994, when the U.S. refugee program welcomed nearly 112,000 refugees. Yet, due to the scale of the current refugee crisis, the number represents a much smaller portion of persons displaced from their homes by violence and persecution around the world than in 1994.

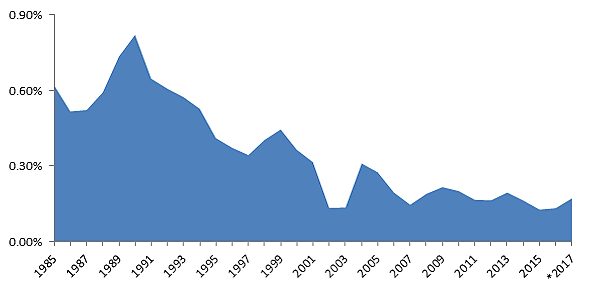

As Figure 1 shows, the U.S. program took almost a half a percent of the displaced population, as estimated by the United Nations, in 1994. Next year, it will take just 0.17 percent. The average since the Refugee Act was passed in 1980 has been 0.48 percent. There was a huge drop-off after 9/11, as the Bush administration attempted to update its vetting procedures, and although the rate rebounded slightly, it continued its downward descent.

Figure 1: Percentage of the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees Population of Concern Admitted Under the U.S. Refugee Program (FY 1985–2017)

Sources: United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, U.S. Department of State. *The 2017 figure uses the 2016 UN estimate and assumes that the U.S. will reach its 2017 goal.

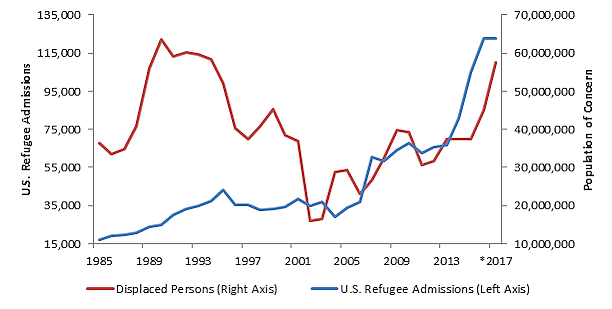

But as the Obama and Bush administrations slowly ramped up the refugee program after 2001, the increases could not keep up with the number of newly displaced persons. Today, the number of displaced persons has reached its highest absolute level since World War II. As Figure 2 shows, the U.S. refugee program has almost returned to its early 1990s peak in absolute terms, but all of the increases in the program since 2001 have been matched by even greater increases in the number of displaced persons.

Figure 2: Admissions Under the U.S. Refugee Program and U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees Population of Concern (FY 1985–2017)

Sources: See Figure 1 (Figure was updated due to incorrect labelling)

The increase in the refugee target for 2017 is still an improvement, but if it is to be anything other than a completely arbitrary figure, it should be based primarily on the international need for resettlement. The Refugee Act of 1980 states that the purpose of the program is to implement “the historic policy of the United States to respond to the urgent needs of persons subject persecution.” In other words, it should be a calculation based first on the needs for resettlement.

If the U.S. program accepted the same rate as it has historically since the Refugee Act was passed in 1980, it would set a target of 300,000 refugees for 2017. If it accepted the average rate from 1990 to 2016, the target would be 200,000. This is the amount that Refugee Council USA—the advocacy coalition for the nonprofits that resettle all refugees to the United States—has urged the United States to accept.

The decline in the acceptance rate for the U.S. refugee program also highlights the inflexibility of a refugee target controlled entirely by the U.S. government. White House spokesman Josh Earnest said that the president would have set a higher target, but because accepting refugees is “not cheap,” and congressional appropriators were not on board with the plan, they could not.

As I’ve argued before, the United States could accept more refugees using private money and private sponsors without needing Congress’s sign-off. The United States used to have a private refugee program in the 1980s, and for decades before the Refugee Act of 1980, the United States resettled tens of thousands of refugees with private money.

Canada currently has a private sponsorship program that is carrying the disproportionate weight of its large refugee resettlement program, with better results than the government-funded program. Other countries are following Canada’s example, it’s time the United States do so as well

There should be no limits on American charity. If American citizens want to invite people fleeing violence and persecution abroad to come into their homes, the government should not stand in their way. In the face of this historic crisis, the United States should allow Americans to lead a historic response that is consistent with our past.