As I noted on Wednesday, the Senate is now considering “The United States Innovation and Competition Act of 2021” (formerly known as the “Endless Frontier Act”), which is primarily* intended to boost federal funding for research and development in the United States by tens of billions of dollars. If you were to listen to the bill’s advocates, you’d think that the United States was suffering from a dramatic decline in R&D spending over the last several decades, and that other countries — particularly China — had raced ahead. New data from the U.S. and National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics (NCSES) and the OECD, however, paint a different picture.

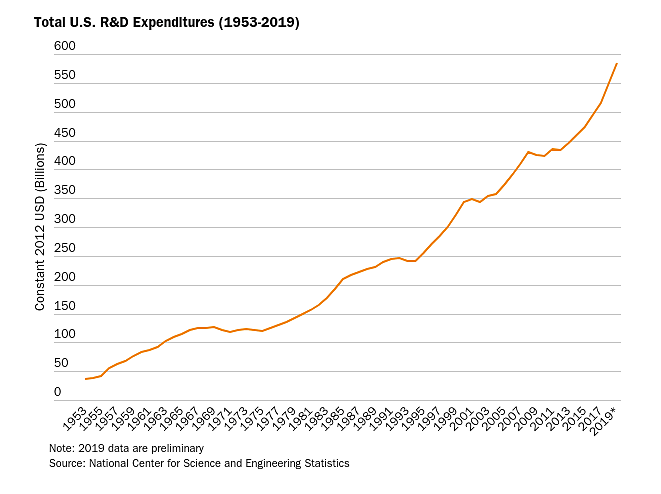

First, the NCSES’ latest report on R&D expenditures shows that total U.S. spending reached an all-time high in 2019, both in total, inflation-adjusted dollars ($584.4 billion) and as a share of GDP (3.06%):

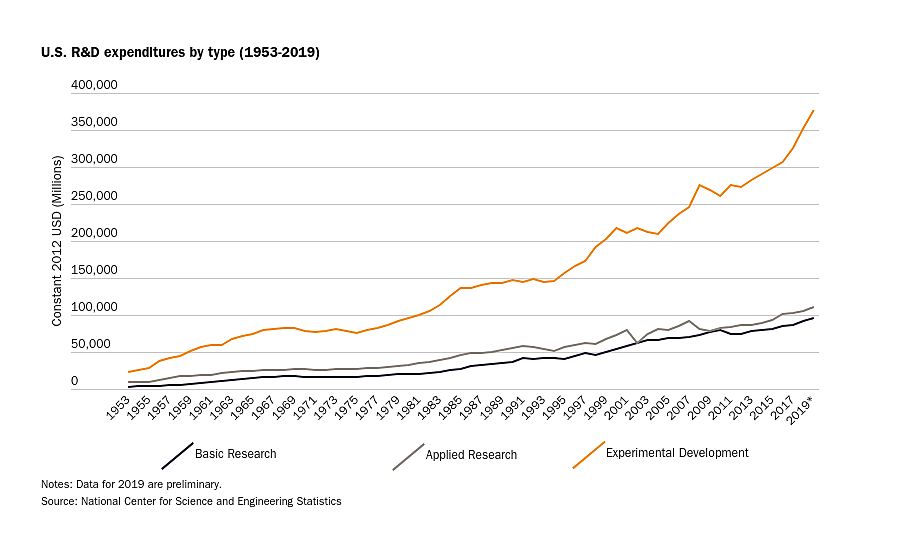

That same dataset shows that all forms of R&D — basic, applied, and experimental development — also hit all-time highs in 2019:

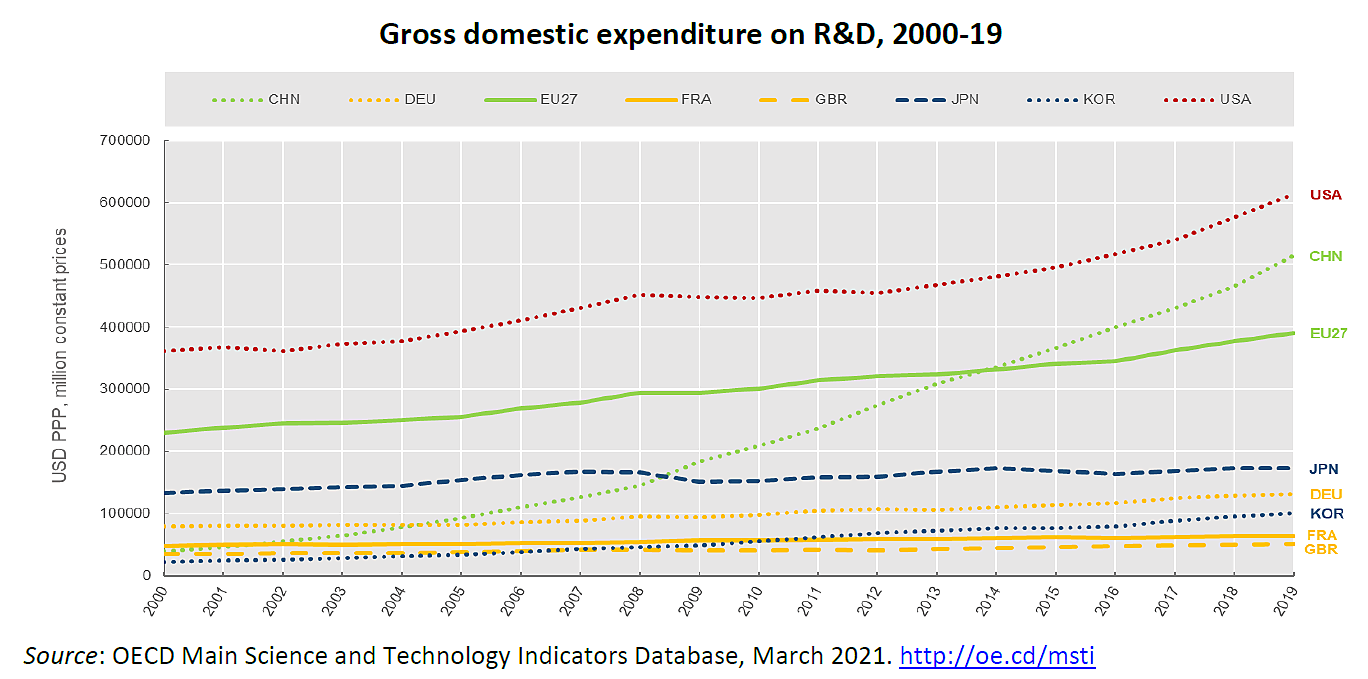

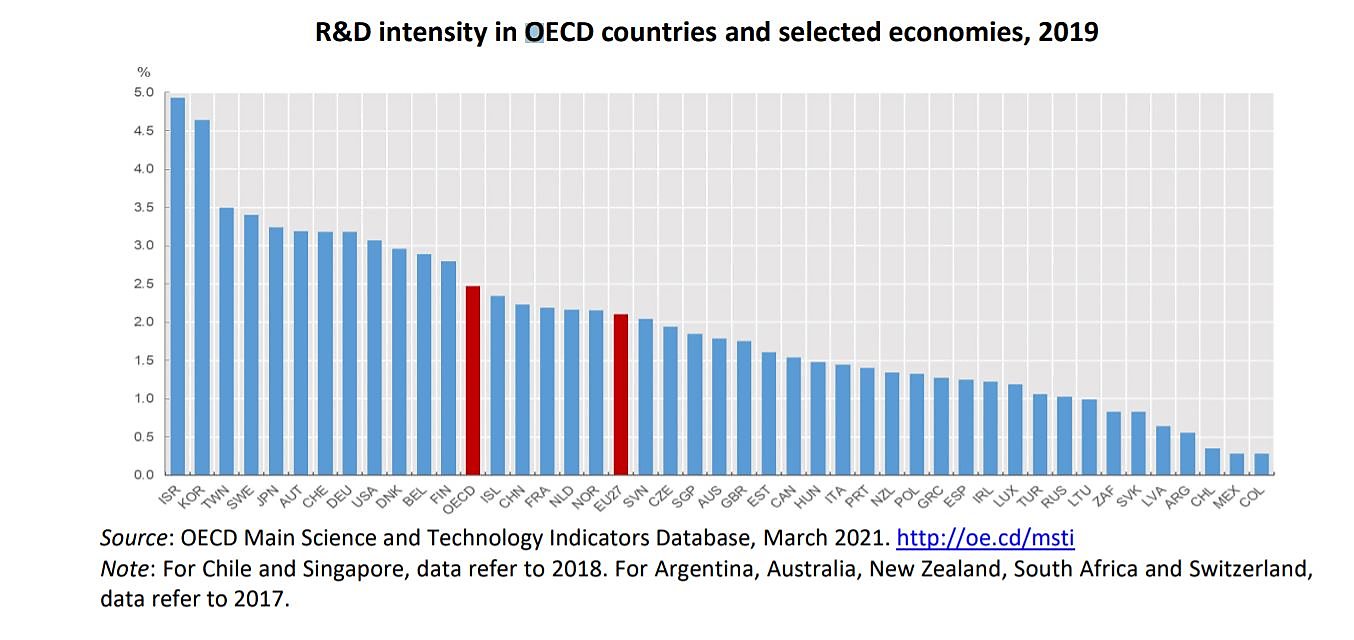

The OECD, meanwhile, shows that the United States still leads the world in gross R&D expenditures and is among the top 10 in R&D intensity (GDP share), still well above China in both categories:

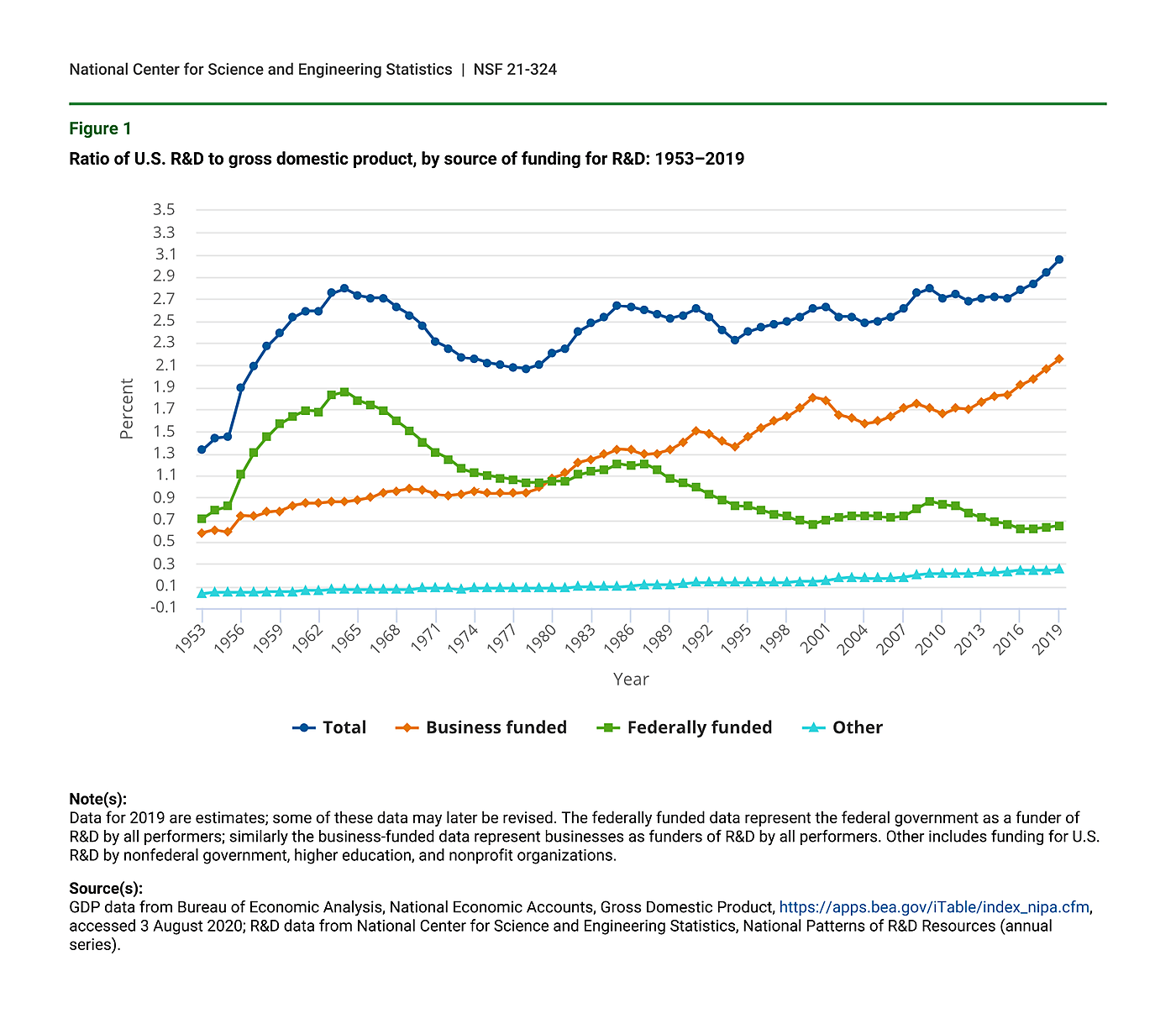

Of course, total dollar amounts alone can’t tell us everything we need to know about a nation’s innovative capacity. However, the data above should at least warrant skepticism about the need for tens of billions of taxpayer dollars in new federal R&D spending and likewise demand hard proof from advocates that government funds will actually boost American innovation. On the latter score, for example, we know that massive semiconductor subsidies in China (the legislation’s clear target) haven’t produced a cutting-edge, world-beating industry, and that — as Cato adjunct Terence Kealey and others have written — government R&D spending risks crowding out private spending (and thus not boosting national R&D expenditures overall). The first chart above, showing private and federal R&D spending moving in opposite directions, provides some support for the crowd-out thesis. As I’ve discussed here, moreover, various data and anecdotal evidence indicate that private R&D expenditures in key U.S. manufacturing industries — such as semiconductors, electric vehicles (and batteries, in particular), and pharmaceuticals — are solid, if not world-class.

And then, of course, there is the much-deserved concern that any textbook case for government R&D spending will be eviscerated by the political process necessary to implement it — a concern that’s already proven justified for this particular bill.

Put it all together, and the supposedly urgent need for the USICA melts away. Fortunately, the bill still has a ways to go before it becomes law.

*There’s also a ton of pork and other stuff in there, but more on that later.