I still have a 1979 bookmark that says, “INFLATION IS A PAIN IN THE GAS.”

Funny but wrong. U.S. gasoline prices follow gyrations in world oil markets, which depend on global (not domestic) supply and demand.

What actually happened in 1978–80, an important German study from Bruegel reminds us, was the Iranian revolution and the Iran-Iraq War: “The 1978 Iranian revolution decreased global supply by 4 percent and led to a price increase of 57 percent. The 1980 Iran-Iraq war decreased global supply by 4 percent and led to a price increase of 45 percent.”

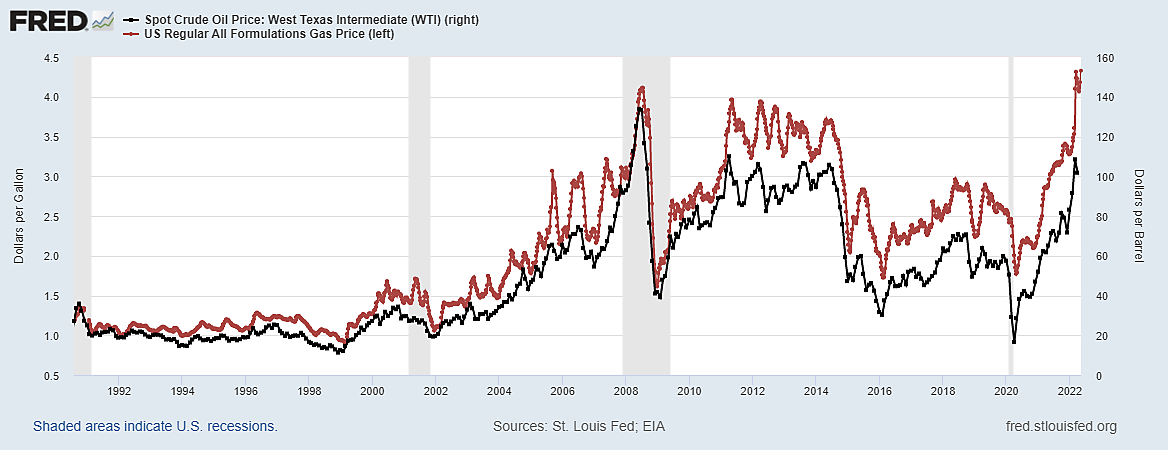

What happened to world oil markets in 2020 was a global pandemic, with falling oil and gas prices followed by a sizable loss of oil and gas production capacity in the U.S. and elsewhere. What happened in 2021 was mostly the phasing-out of governmental lockdown schemes which allowed production, commerce, and transportation to bounce back faster than oil and gas production could. China, however, has lately reverted to primitive lockdown schemes, which might lower world demand for oil and everything else by shrinking the Chinese economy.

What happened to crude oil and gasoline prices in 2022 was the Russian invasion of Ukraine, though partisans falsely deny the link between war and oil markets and instead blame President Biden for U.S. gasoline prices – which, as in 1979, are considered synonymous with “inflation.”

Recently, the oil futures market has been rattled by proposed EU sanctions intended to shrink the world supply of Russian oil.

The U.S. retail price of gasoline reached a record high of $4.37 a gallon yesterday, while global news pushed the price of WTI crude oil future down by 6.1%. The next day, “Crude oil futures were sharply lower in mid-morning Asian trade May 10, extending steep overnight declines,” due to “hurdles to an European Union-ban on Russian oil and the ongoing spread of COVID-19 in China.” The Financial Times noted, “Brussels has shelved its plans to ban the EU shipping industry from carrying Russian crude as it struggles to push through its latest sanctions package because of anxiety among some member states about the economic impact of the measures.”

The Bruegel study notes, “Such a measure would not prevent Russia from exporting altogether – it would find alternative buyers, such as China, India or others, as it already does – but an embargo would certainly increase the discount on Russian oil… If, on net, Russian exports decreased, the world price would go up, unless the drop in Russian exports was offset by the decisions of other producers, from Saudi Arabia to Iran to Venezuela, to increase production.”

Regardless of the net effect of a hypothetical EU ban on Russian oil, the fact that it suddenly appeared far less likely to happen was followed by lower world oil prices and higher prices for U.S. bonds and stocks. If the world (and U.S.) price of crude oil remains lower for a while, then U.S. gasoline prices will also turn down later.