Yesterday, President Trump and Chinese Vice Premier Liu He signed a “phase one” U.S.-China trade deal. A “phase two” deal may be coming, although the timing is unclear, and many people (including us) are skeptical that it will happen any time soon. There are some technical and complicated parts of the phase one deal, and it will take some time to digest it all and come up with an overall evaluation. But it’s worth exploring some specific aspects right away. One of the most talked about parts of the phase one deal is the commitments by China to purchase large amounts of U.S. products, including agricultural products. Article 6.2, paragraph 1 of the deal has broad details of these purchases:

During the two-year period from January 1, 2020 through December 31, 2021, China shall ensure that purchases and imports into China from the United States of the manufactured goods, agricultural goods, energy products, and services identified in Annex 6.1 exceed the corresponding 2017 baseline amount by no less than $200 billion.

Given that U.S. exports to China in 2017 were about $180 billion, an additional $200 billion over two years would be a massive increase. The deal further divides up these purchases into manufactured goods, agricultural goods, energy, and services, with specified amounts for each. It then provides sub-categories, but it does not publicly break down the purchase amounts by sub-category (apparently it does so in a confidential version of the text).

This is not a typical trade deal. A normal trade deal would focus on liberalizing trade in both directions (although modern trade deals have gone beyond that and do a lot of regulating). By contrast, this trade deal is an extreme version of managed trade, with China agreeing to buy designated amounts of U.S. products (supposedly “based on market conditions”).

Beyond the problematic policy goals, it remains to be seen what all of this means in practice. Here are a few questions that arise: How exactly will China quickly ramp up its purchases? What is the role of the government in this shopping spree? What domestic process will the Chinese government use to induce companies to make these purchases? Are there accounting tricks they can rely on (e.g. reclassifying current Hong Kong imports as Chinese imports)? Will these companies shift current purchases of these products away from other countries’ producers and over to U.S. producers (and will those other countries be annoyed)? Can U.S. producers scale up production to meet these targets?

A wide range of products have been mentioned in this context, and how this plays out might vary by product. To help assess this, we thought it might be useful to focus on one product in particular. We are going to use beef as an example (a former Trump administration trade official was recently reported as having confirmed that “there would be purchases of poultry and beef – estimated at US$1.5 billion apiece – in the phase one deal, with American farmers gaining re-entry to the market after years of being left out in the cold due to China’s ban on certain hormones and additives used in US farming.”)

So how might U.S. beef exports to China fare as part of China’s promised purchases? Two years ago, we wrote about the possibility of increased U.S. beef exports to China. The removal of Chinese restrictions on U.S. beef — which had been put in place by many countries in 2003 after a BSE scare — was a key component of the 100-Day Action Plan reached between the Trump administration and Chinese officials in May 2017. As we explained then, China had become a big consumer of beef, and imports of beef into China were increasing. While many countries saw their beef sales rise, U.S. beef exports to China had been negligible due to the BSE restrictions. Removal of the Chinese restrictions was likely to help.

Unfortunately, the U.S.-China trade war got in the way. As a result of the retaliatory tariffs that China imposed in response to U.S. tariffs, most U.S. beef exports to China faced additional tariffs, beyond the normal Chinese tariffs, of between 10 percent and 35 percent, much higher rates than faced by their competitors in other countries. (Some of those competitors had negotiated free trade agreements with China, giving them an even bigger advantage).

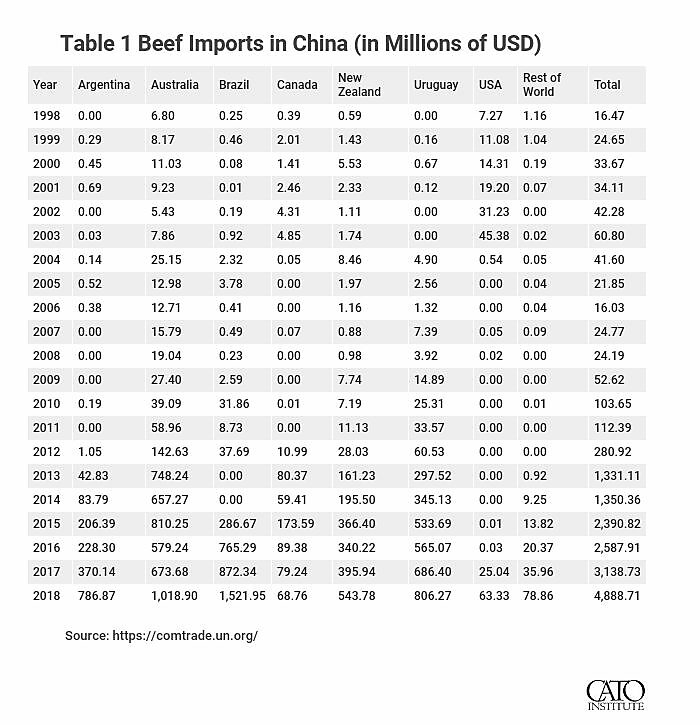

As shown in Table 1, after the 100 Day Action Plan, the United States increased its beef exports to China from a negligible amount to $63 million in 2018. That was a good start. However, that number is only a small fraction of the total growth of imports of beef into China in that period, from $2.6 billion to $4.9 billion. Imports from other major beef-exporting countries, including Argentina, Australia, Brazil, New Zealand, and Uruguay, all witnessed a much larger jump than U.S. beef did.

For a long time, Chinese consumers preferred other meat products over beef, but as China has grown wealthier, their tastes have changed. As the table shows, their interest in beef has increased considerably. This is a development that U.S. producers should be able to take advantage of, but so far have done so only to a limited extent, whereas their rivals are moving much more quickly. Without a doubt, the Chinese retaliatory tariffs have been a significant factor.

Now with the phase one deal in place, it is likely there will be a tariff waiver on the relevant agricultural products, which will give U.S. producers a better chance to compete. In addition, language in the deal on certain regulatory issues may also help boost beef exports to China. For instance, China promised to remove the age limit for U.S. cattle, which had prohibited sales of meat from cattle over 30 months old at the time of slaughter.

However, U.S. beef sales will still face some hurdles: Their competitors have a big head start and have been developing relationships with Chinese customers for years; some competitors have free trade agreements with China and thus their products are subject to special, low tariffs; and China has had restrictions on sales of hormone-treated beef, which is a significant portion of U.S. production. (Under Annex 4 of Chapter 3, it looks like the issue of restrictions on hormone-treated beef will be addressed to some extent, which would be a big deal for U.S. producers.)

Market-sharing managed trade arrangements are a bad way to approach trade agreements, but even putting that aside, there is still the question of whether they work. It will be interesting to see how the U.S. strategy is effective here. Regardless of how it plays out, a better strategy would have been to push for an agreement like the ones Australia and New Zealand have with China, in order to get China to lower its tariffs further, rather than just restoring them to the pre-trade war level.