Launching the Center for Educational Freedom’s new book School Choice Myths: Setting the Record Straight on Education Freedom has taken up a lot of my time over the last couple of weeks, so I haven’t been able to post a summary of our data on the health of private schooling under COVID-19. But it’s not too late to pull it together, even as the state of K‑12 schooling continues to evolve.

Closures

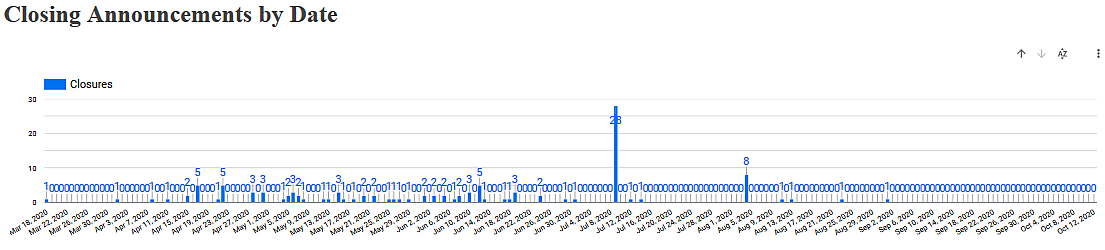

The good news is we have not seen the kill-off of private schools that many—myself included—feared at the outset of lockdowns. Our permanent closure tracker has not recorded a COVID-connected closing since September 1 and the total stands at 116 schools, reduced to 111 when school consolidations are considered. That is a tiny fraction of the nation’s approximately 32,500 private schools containing at least one grade K‑12.

Of course, it is entirely possible that some permanent closures have not come to our attention. Many private schools are very small—almost a third have fewer than 50 students—and some schools may have ceased operations without any public announcement.

In early September we conducted a survey of 400 private schools randomly selected from the federal Private School Universe database and found 6 that had closed since the data was collected in the 2017–18 school year. 4 appear to have closed in 2020, but only 1 with an explicit connection to COVID, 1 before COVID, and 2 announced during the lockdown period but with unknown COVID connections. That suggests that less than 1 percent of private schools have closed due to COVID, consistent with our tracker numbers.

Enrollment

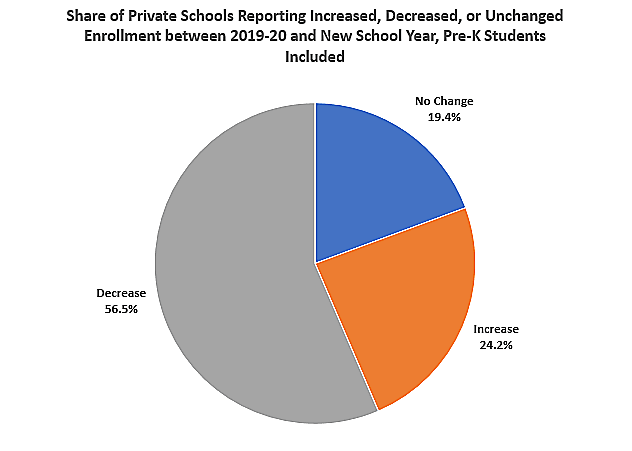

We have also seen private schools lose students, as anticipated. It is difficult for many people to pay tuition when they can access “free” public schools, for which, of course, they have had to pay taxes. It is even harder when families have suffered income reductions and the service was forced online and, hence, was of probably somewhat compromised quality.

According to our survey, about 57 percent of private schools saw enrollment reductions between the previous school year and early- to mid-September of this year, with 24 percent seeing an increase and 19 percent no change. On average, responding schools lost 14 students, or about a 6 percent enrollment reduction. Those numbers include pre‑K students, which many schools with kindergarten and above often have. Set aside pre‑K enrollment and roughly 47 percent of private schools saw declining enrollment, 33 percent increasing, and 21 percent no change. On average schools lost about 6 students.

The 6 percent loss when including pre‑K students would translate into a loss nationally of about 343,000 students from the most recent federal tally of total private school enrollment, which was from 2017.

This trimming of students—many of whom are likely homeschooling, at least temporarily—has not, apparently, been catastrophic for most schools, and numbers have likely been in flux as public school policies have evolved. But many private schools have thin margins and might not be able to sustain many more losses. As WORLD Radio noted in a story about Christian schools under COVID, which have seen similar enrollment trends to what we found for all privates, “Losing 7 percent of the student body may not sound like a lot, but for Christian schools that operate on tight margins those losses add up.”

Conclusion

Private schools are not folding at the rate we feared, but they are hurting, even as they have responded more quickly to families than have public schools. To retain these diverse institutions—and much more importantly, the ability to choose—money needs to follow children, whether it is via any federal relief that might come down the pike, or state education funding. We need to stop funding institutions and start funding children.