My op-ed today at The Federalist discusses exciting developments in Canada and Britain regarding personal savings. Both nations have implemented universal savings vehicles of the type I proposed with Ernest Christian back in 2002. The vehicles have been a roaring success in Canada and Britain, and both countries have recently expanded them.

In Canada, the government’s new budget increased the annual contribution limit on Tax-Free Savings Accounts (TFSAs) from $5,500 to $10,000. In Britain, the annual contribution limit on Individual Savings Accounts (ISAs) was recently increased to 15,240 pounds (about $23,000). TFSAs and ISAs are impressive reforms—they are pro-growth, pro-family, and pro-freedom.

America should create a version of these accounts, which Christian and I dubbed Universal Savings Accounts (USAs). As with Roth IRAs, individuals would contribute to USAs with after-tax income, and then earnings and withdrawals would be tax-free. With USAs, withdrawals could be made at any time for any reason.

USAs, TFSAs, and ISAs adopt the principle that saving for all reasons is important, not just reasons chosen by the government. When people can use such accounts for all types of saving and for any length of time, it increases simplicity, flexibility, and liquidity.

In the United States, the government chooses which savings to favor, with the result that we have a mess of separate accounts with different rules for retirement, health care, and education. Everyone agrees that Americans don’t save enough, and one reason is the complexity of savings accounts. The creation of large accounts for all types of saving would simplify personal financial planning and encourage more saving.

There are differences between the Canadian and British accounts. While the annual contribution limit is lower for TFSAs than ISAs, unused contribution amounts can be carried forward under the TFSA, but not the ISA. Also, the TFSA is simpler because it is a single type of account. By contrast, the Brits created unneeded complexity by having separate “cash” and “stocks and shares” versions of ISAs.

Dividends, interest, and capital gains earned within TFSAs and ISAs are completely tax-free. Some U.K. news articles say that higher-earners may face a 10 percent dividend tax on shares held within ISAs. That is not correct, as Richard Teather confirmed to me. The U.K. has a complicated system for non-ISA dividends, which involves the use of a 10 percent dividend credit. That seems to have confused some reporters about dividends within ISAs.

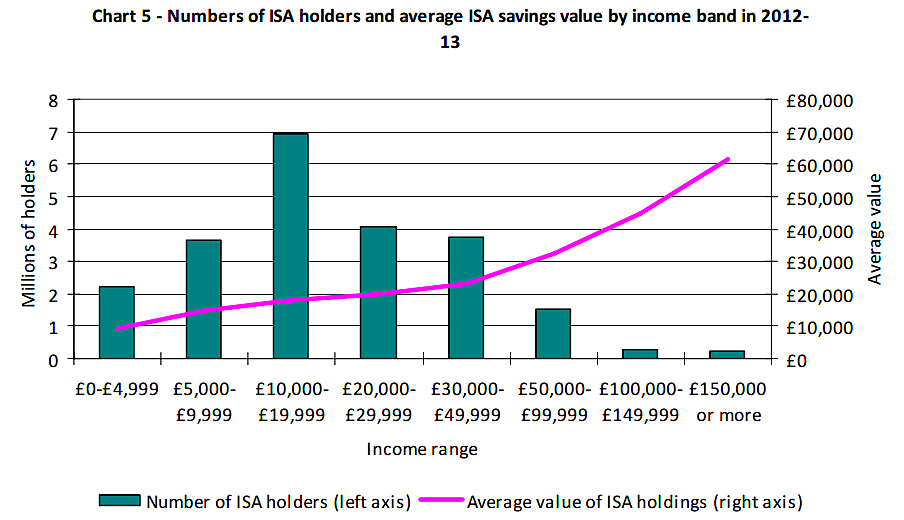

If legislation to enact USAs moves ahead in America, we might expect complaints that such accounts would only benefit high earners. Such complaints would be both short-sighted and incorrect. In this new report, HM Revenue and Customs data show that ISAs have broad-based appeal in Britain. The columns in the chart below show that 13 million of the 23 million ISA account holders earn less that 20,000 pounds (about $30,000) a year. That high level of use by moderate-income individuals is great news.

The red line shows that the average value of accounts rises with income. That is not surprising given that people with higher incomes do more saving, which, by the way, is good for the overall economy. But note that the relative level of holdings is higher for people nearer the bottom. For example, earners in the 10,000–19,999 income range hold about 18,000 pounds of assets in their ISAs, so the average holding is about as high as annual income. But for higher earners, average account holdings are only a fraction of annual income.

In sum, policymakers in the United States have put too much emphasis on giving certain groups narrow tax breaks. USAs would be a better policy approach because they would help all Americans help themselves through their own thrift.

For more on universal savings accounts, see my op-ed with Amity Shlaes.