At the end of last week, the Labor Department reported that the share of private-sector workers who belong to labor unions fell to its lowest level in more than a century.

In 2009, the “union density” in the private sector fell to 7.2 percent, the lowest it has been since 1900. The recession caused the number of private-sector union members to fall by 10 percent last year, with the heaviest losses in manufacturing and construction.

Not surprisingly, union membership held steady in the public sector, with the share of government workers belonging to unions actually inching up to 37.4 percent. Unionization is more viable in the public sector because the additional costs imposed by unions can be passed along to captive taxpayers.

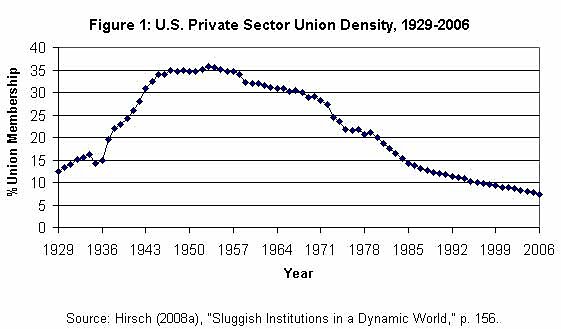

The economics of unionization are much different in the private sector, as I argue in an article in the latest issue of the Cato Journal now available online. In a competitive market, producers cannot pass the costs of unionization on to consumers without the real risk of losing market share to non-unionized rivals. This is a major, self-serving reason why organized labor typically opposes competition-enhancing trade agreements with other countries. (See the chart below from my Cato Journal article.)

The drop in union members was also another piece of bad news for the Democratic Party last week. As labor unions have become relatively more important as a constituency within the Democratic Party, they have become increasingly irrelevant in the private economy. Unions will find it more and more difficult to generate the funds for their political activities if the number of dues-paying members continues to slide.