Two experiments in a new working paper find some evidence that some drivers using popular ride-hailing platforms discriminate against riders. In some cases African-American riders faced longer wait times or higher probabilities of having a driver cancel on them. To some extent, these findings should temper hopes that these new technologies and platforms would succeed in quickly rooting out these forms of discrimination. It is important to note, however, that this study examined whether there was discrimination within these platforms, it did not compare ride-hailing platforms and traditional taxi companies. These new platforms do offer some advantages over the status quo when it comes to identifying the channels of discrimination through richer data, while the rating system gives riders some recourse to penalize discriminating drivers and an incentive for drivers to maintain a high rating.

In the study the researchers undertook two large-scale experiments to try to determine whether there was a pattern of discrimination for riders using these ride-hailing platforms.

In the Seattle experiment research assistants of different racial backgrounds requested rides along pre-determined, randomized routes. They logged speed of service, directness of the route, and the passenger ratings received. For each of the services analyzed (UberX, Lyft, and the traditional taxi-hailing app Flywheel), African-American riders had longer acceptance times than white riders. In UberX, they also waited about 30 percent longer to be picked up, while there were no significant differences in the other two.

In Boston, research assistants varied the names they used to request rides, with one more “white sounding” and the other a “distinctively black name.” Here wait times and acceptance times did not differed significantly, in one platform the rate of trip cancellations did: in UberX the rate of cancellation for hailers using African American-sounding names was 10.1 percent, compared to 4.9 percent for the white-sounding names, while there were not signs of racial discrimination in Lyft (and women using the African-American names actually had a lower cancellation rate).

Some of this variation in discrimination might be due to differences in the way platforms provide rider information to the drivers. Lyft drivers see the passenger name and photo (if the passenger has chosen to upload one into their profile) before accepting a ride request, in UberX the drivers only get a name after accepting, and in Flywheel there are no passenger photos in traveler profiles at all. The authors suggest that platforms could alter the timing and content of the rider information provided to reduce the possible channels for discrimination.

Again, this study examines whether there are signs of discrimination within these ride-hailing platforms, that is, differences in wait times, routes, and acceptance rates by gender or race. As the authors are careful to point out, they “do not claim that [transportation network companies] are “worse” than the status quo.”

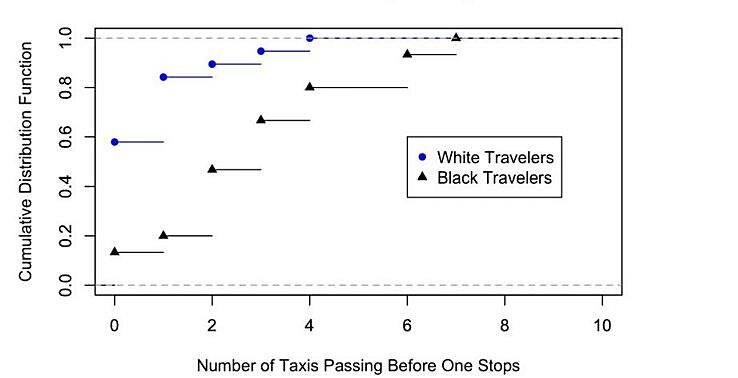

The authors do provide one brief illustration of the discrimination present in traditional taxis, and find that there is also a substantial different in acceptance rates for traditional taxis when research assistants of different racial background tried to hail a cab. The first taxi stopped roughly 60 percent of the time for a white hailer, compared to less than 20 percent of the time for an African-American rider. White riders never had more than four taxis pass before one stopped, while African-Americans saw six or seven taxis pass by in 20 percent of the time. So there is unfortunately a substantial amount of discrimination in the traditional taxi industry, but it is has been opaque and harder to measure or understand. Also, riders who are discriminated against in those instances have fewer options to choose a different platform, give the offending drivers negative feedback, or provide information to the taxi company to make the extent of the discrimination clear.

Number of Traditional Taxis Passing Waiting Travelers, by Race

Source: Ge et al. (2016).

While these ride-hailing platforms may offer many improvements over traditional taxis when it comes to convenience and cost, this new paper shows that some individual drivers discriminate against riders on the basis of their race or gender. It’s not clear how this level of discrimination compares to traditional taxis, and the study shows that there is a significant amount in the old framework as well. These new platforms make it easier for riders and companies to identify which drivers are doing this, and they give riders more recourse to penalize offending drivers and more options to choose from that might be better on these measures.

Armed with this new information and a fuller understanding of how this driver discrimination is taking place, platforms can experiment with changes to the timing and content of the rider information they provide to drivers to try and address these issues. Ride-hailing platforms have not yet solved the difficult problem of discrimination in that sphere, but they might still make significant progress in reducing it, and they can do it without the need for heavy-handed new government intervention.