It occurs to me that recent discussions of the Fed’s new average inflation targeting plan gloss over a subtle distinction between two different kinds of Average Inflation Targeting (AIT). Hence this post explaining the difference, and why I think it matters.

The difference between the two sorts of AIT that I have in mind is subtle, so pay close attention! It hinges not on any different central bank objectives or reaction function parameters or that sort of thing, but on two different reasons why a central bank might find that it has veered from its inflation target in the first place. A central bank may fail to hit its target because the authorities fail to correctly anticipate upcoming changes in various price level determinants. Call such misses “unexpected target deviations.” Or it may fail because, although its forecasts are correct, circumstances prevent it from adjusting its stance as needed, given its forecast, to keep the price level on target. Call these “expected target deviations.” The “zero lower bound” (ZLB) problem is the most conspicuous example of a circumstance that could lead to expected target deviations. Allowing that unconventional policies are either impractical or inadequate, a central bank stuck at the ZLB may know perfectly well that it’s about to undershoot its inflation target, without being able to avoid doing so.

It turns out that the implications of AIT, understood as a means for eventually making up for previous, unwanted price level movements, and consequent changes in the ex-post rate of inflation, differ dramatically depending on which sort of target deviations it’s trying to make up for. It turns out that, while AIT has considerable advantages when the deviations it makes up for are unexpected, it’s likely to prove far less advantageous, and perhaps even to prove detrimental, as a means for catching up after expected deviations like those that can occur when the ZLB is binding. Unless AIT is going to prove harmful in practice, these alternative possibilities had better be better understood.

To explain them, I’m going to make some simplifying assumptions. First, I’ll assume that a central bank sets an inflation rate target of zero. That is, it wants to keep the price level perfectly stable in the long run. This makes it easy for me to draw some figures. Rather than expect me to deal with sloping lines, you are free to imagine any alternative inflation rate target you may prefer by tilting your computers accordingly.

Second, I’m only going to consider cases in which the central bank occasionally undershoots its inflation target—that is, ones in which the price level drops below its target level. In the first case, this happens because of unanticipated, permanent drops in the velocity of money (or, if you prefer, unanticipated jumps in the public’s preferred ratio of money balances to income): the ZLB is never binding. In the second, it happens because of temporary, negative shocks to the the equilibrium or “natural” real rate of interest which, given the prevailing expected inflation rate, place the target-consistent central bank policy rate temporarily below the ZLB. In that case, I will assume that “unconventional” policies are ineffective at generating inflation. Finally, and again for simplicity’s sake, I’m going to assume that, under a strategy of strict (that is, forward-looking) inflation targeting, in which the central bank does not attempt to make up for past target misses, both cases would lead to identical cyclical price level and output movements.

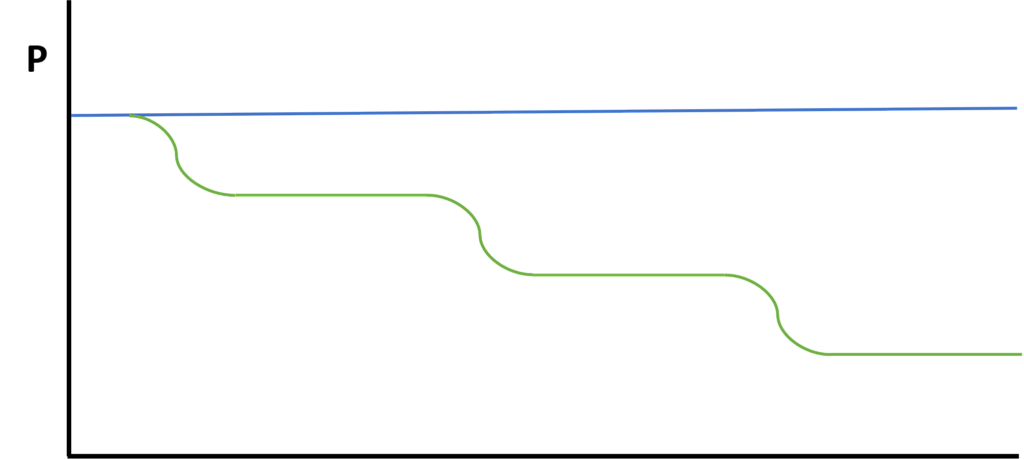

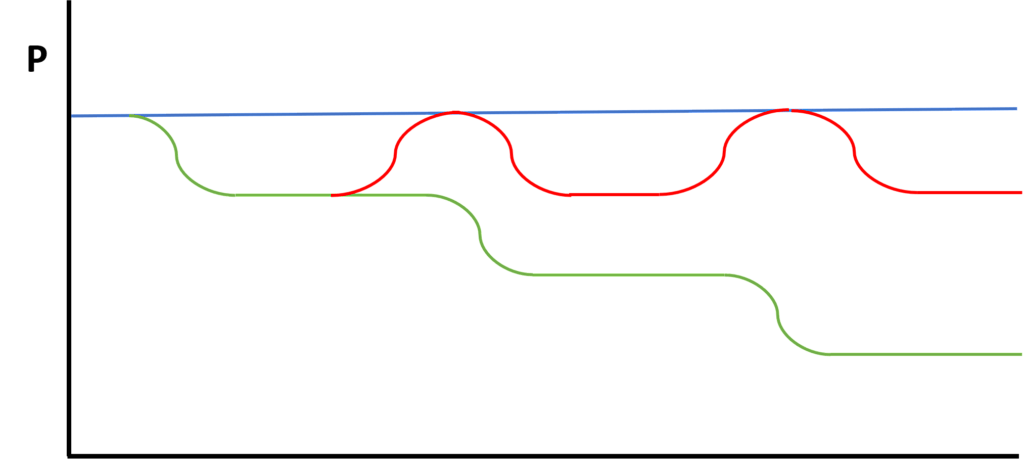

Because the central bank’s stance is occasionally too tight, but never too loose, in both instances, the price level and output movements will be of the sort implied by Milton Friedman’s famous “plucking” model. Here is the price level path, assuming strict inflation targeting, where the blue line is the target, and the green line is the actual price level.

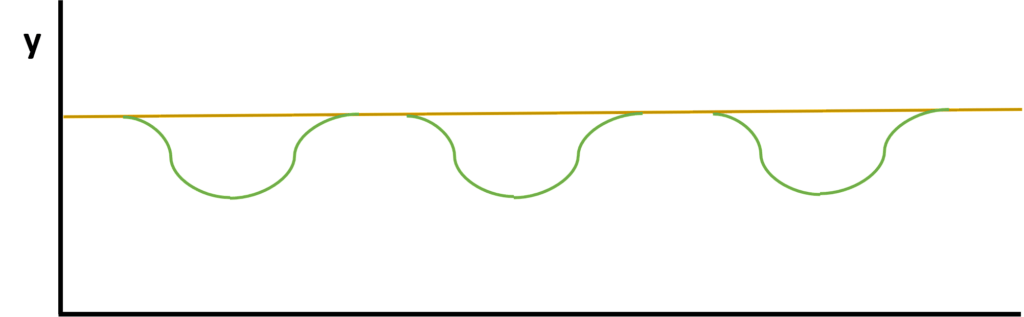

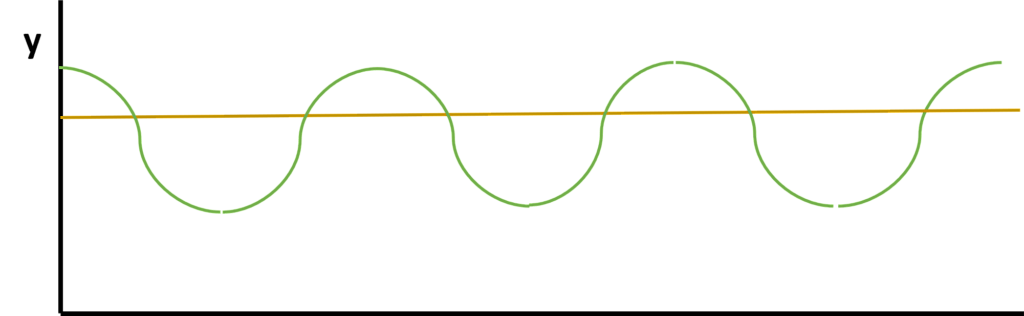

And here is the implied path of real output:

Viewed as an alternative to strict IT, AIT can have several aims. Most obviously, it serves to keep the long-run inflation rate on target. It can also contribute to a more rapid recovery from recessions or depressions. Finally, if it raises the expected inflation rate (as it will when, under strict IT, undershooting is more common than overshooting), it will reduce the odds that the ZLB becomes binding. But whether it achieves either of the last two aims, and which one it achieves, will depends on which of our two causes is behind the failure of strict IT.

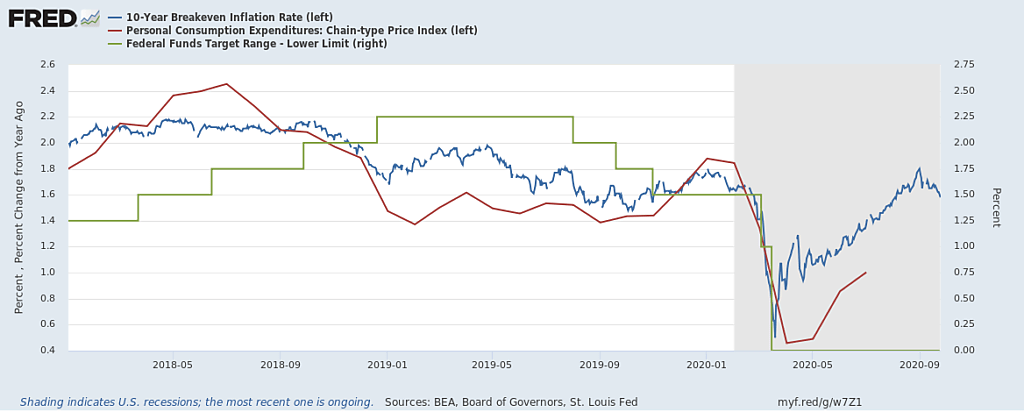

That either cause can be important is easy enough to grasp just by considering the experience of the last few years, as summarized in the following FRED chart:

The chart shows the actual PCE inflation rate (in red), the 10-year breakeven CPI inflation rate—a measure of expected inflation (in blue), and, with its markers on the right scale, the lower limit of the fed funds rate target (in green).

Several things should be evident from the chart. First, for most of the time during which the Fed was reviewing its policies, and most of the period during which it was undershooting its 2 percent inflation target, the zero lower bound was not binding. A binding ZLB only became relevant with the outbreak of the COVID-19 crisis this March. Second, although it was briefly above target in mid-2018, realized PCE inflation was otherwise persistently below target. Yet expected inflation was generally on target until the start of 2019, after which it fell below target, but less so than realized inflation. These facts suggest that until March 2020 inflation undershooting was at least partly a result of Fed miscalculations. Only since then can a binding ZLB be said to have become a definite cause, if not the chief or sole cause, of below-target inflation.

It’s far from clear which sort of inflation undershooting the Fed had in mind in deciding to switch from IT to AIT. What’s certain is that both the way in which AIT is implemented and the consequences of resorting to it are bound to differ depending on whether or not a binding ZLB is to blame for below-target inflation.

Why is that? Because, when undershooting is the result of Fed error, the Fed can begin making up for it as soon as it likes, by setting a policy rate consistent with some above-target level of expected inflation. In contrast, if inflation falls below target owing to a binding ZLB, the Fed cannot begin to make up for it until the ZLB ceases to bind. Put another way, in the first “mistake” case, the Fed can move to a more inflationary stance while the downturn is in progress, and the quicker the better. In contrast, in the “ZLB” case, it cannot do so until the recovery is well underway. The obvious implication is that, while the sort of AIT that serves to make up for Fed errors of judgement may be a more aggressively countercyclical policy than IT, the sort that serves to make up for time spent at the ZLB is likely to be procyclical.

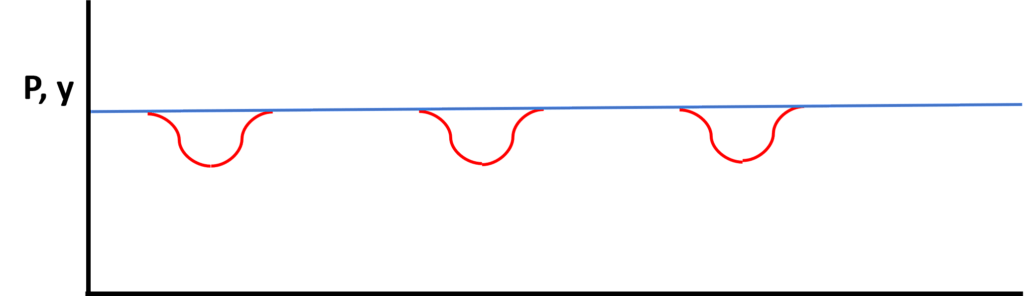

Turning back to our schematics, in the “unexpected deviation” case, the switch from IT and AIT, if done properly, reduces the amplitude of the “plucking” of both the inflation rate and output: a temporary quickening of inflation serves to hasten the return of both the price level and real output to their pre-shock levels. (To save effort, I’ll just assume that the movements in P and y are similar enough to be represented by one picture. ) AIT doesn’t just keep inflation on its long-run target of zero: it can also make contractions less severe and shorter.

Now let’s consider what the price level looks like when undershooting results from a binding ZLB. Recall that the main difference from the previous case is that the make-up inflation cannot begin until the economy has already begun to lift-off from the ZLB, that is, until recovery is underway.

Obviously, AIT still serves to keep the inflation rate on target. To that extent, and assuming that undershooting is more likely than overshooting, it also helps to reduce the probability of a binding ZLB.

So far, so good. But the picture starts to look less rosy once we consider the effect of all this on output. Because inflation overshooting—which in our simple set up is equivalent to NGDP overshooting—now happens during the recovery stage of the cycle, it can no longer be counted on to merely hasten a return to normal output. Instead, as Scott Sumner has recognized, it can mean stimulating an economy that no longer needs it. To the extent that it does (which will depend on how far above target the Fed is willing to go or, what amounts to the same thing, how quickly it seeks to make up for its past undershooting), AIT may have the serious, unintended consequence of turning our “plucking” economy into a boom-bust economy, meaning one with cycles of greater amplitude. Like Icarus, the Fed may find that, to avoid flying too low, it instead ends up flying too high, with the same ultimate result.

Nor is this danger one to be set aside lightly: most U.S. downturns since the mid-1980s have followed fast on the heels of years of above-average nominal income growth.

Because bigger booms tend to mean more serious busts, we reach the paradoxical conclusion that AIT (considered, as always, as an alternative to IT) is least likely to prove helpful in avoiding the ZLB when it is treated as a means for catching up to a central banks’ long-run inflation target following a binding ZLB episode! More generally, while AIT may be a desirable alternative to IT when inflation misses are the unexpected result of central bank misjudgements, it is unlikely to be so when the misses are due to a binding zero lower bound.

Although Fed officials may have been thinking of making up for mistake-based undershooting while they were considering a switch to AIT, there’s no doubt that the AIT they are now contemplating—and the only kind they can hope to practice at present—is AIT of the potentially harmful, countercyclical sort. In his recent remarks at the Official Forum on Monetary and Financial Institutions, Chicago Fed President Charles Evans clearly had this version of AIT in mind in saying that “if you simply start the [average inflation] clock at the beginning of this year…it’s probably going to take you until 2026 or 2028…in order to average 2 percent.”

That any such delayed catching-up to its missed inflation target might find the Fed contributing to the severity of the business cycle is, I suspect, something that Fed officials themselves recognize. But if so, their awareness of the problem is a problem in itself, for it may cause them to hesitate to follow-through on their commitment to AIT. Suspecting as much, the public will correspondingly discount the Fed’s promise to keep the long-run rate of inflation on target despite an occasionally binding ZLB. The Fed’s announced switch from IT to AIT will then prove less capable, if not completely incapable, of reducing the likelihood of its running up against the ZLB again in the future. The problem here is opposite from that emphasized by some other commentators, to wit: that, should inflation ever exceed its target, the Fed may well hesitate to make up for it if doing so means condoning less-than-full employment.

Let me note, in closing, that in assessing AIT under various circumstances, I’ve not referred to supply shocks. For reasons I gave in in a previous post, their presence further weakens the case for AIT, while strengthening that for either strict IT or NGDPLT.