The Fed’s persistent failure to reach its 2 percent inflation target ever since that target was first made explicit in 2012 has elicited a great deal of commentary in the last couple months, from economists, journalists, and some Fed officials themselves. And well it ought to, for whatever one may think of the Fed’s choice of target, the fact that the Fed has been persistently falling short of it suggests that something is awry, if not with U.S. monetary policy, then perhaps with the U.S. economy more generally.

Although plenty of explanations have been offered for the inflation shortfall, none of them is even close to being satisfactory. Bias or “noise” in the inflation numbers? Bias would explain things if the Fed were targeting some supposedly “ideal” measure of inflation. But it isn’t: it’s targeting the rate of change of the Personal Consumption Expenditure (PCE) index, and so long as that measure of inflation falls below the Fed’s target, the Fed isn’t “really” hitting its self-assigned target, even if the “real” inflation rate is higher than the PCE index suggests. As for noise, it should make the Fed just as likely to overshoot as to undershoot its target. Unemployment still isn’t quite low enough? Despite what some foolish Phillips-curve reasoning suggests, putting more people to work doesn’t make things more expensive. The public’s long-run inflation expectations are down? No doubt. But surely that’s a result, rather than a cause, of the persistently low values of actual (or measured) inflation?

Aggregate Demand is Part of the Story (But Only Part)

Of existing explanations, the least question-begging emphasize the fact that total spending, or its statistical counterparts such as nominal GDP, just hasn’t been growing rapidly enough to achieve the Fed’s inflation target. As Mickey Levy puts it in a paper he gave at last week’s SOMC meeting,

Obviously, if nominal GDP had accelerated in response to the Fed’s aggressive easing as planned, both wages and inflation would have risen faster, and inflationary expectations would be higher.

Scott Sumner has made essentially the same point: “The only way to have low inflation despite low RGDP growth,” he observes,

is if the Fed has such a tight monetary policy that NGDP growth remains slow. And that’s exactly what they’ve done since 2009. If you produce 4% NGDP growth year after year after year [when the norm has been substantially higher] then why be surprised that inflation remains low?

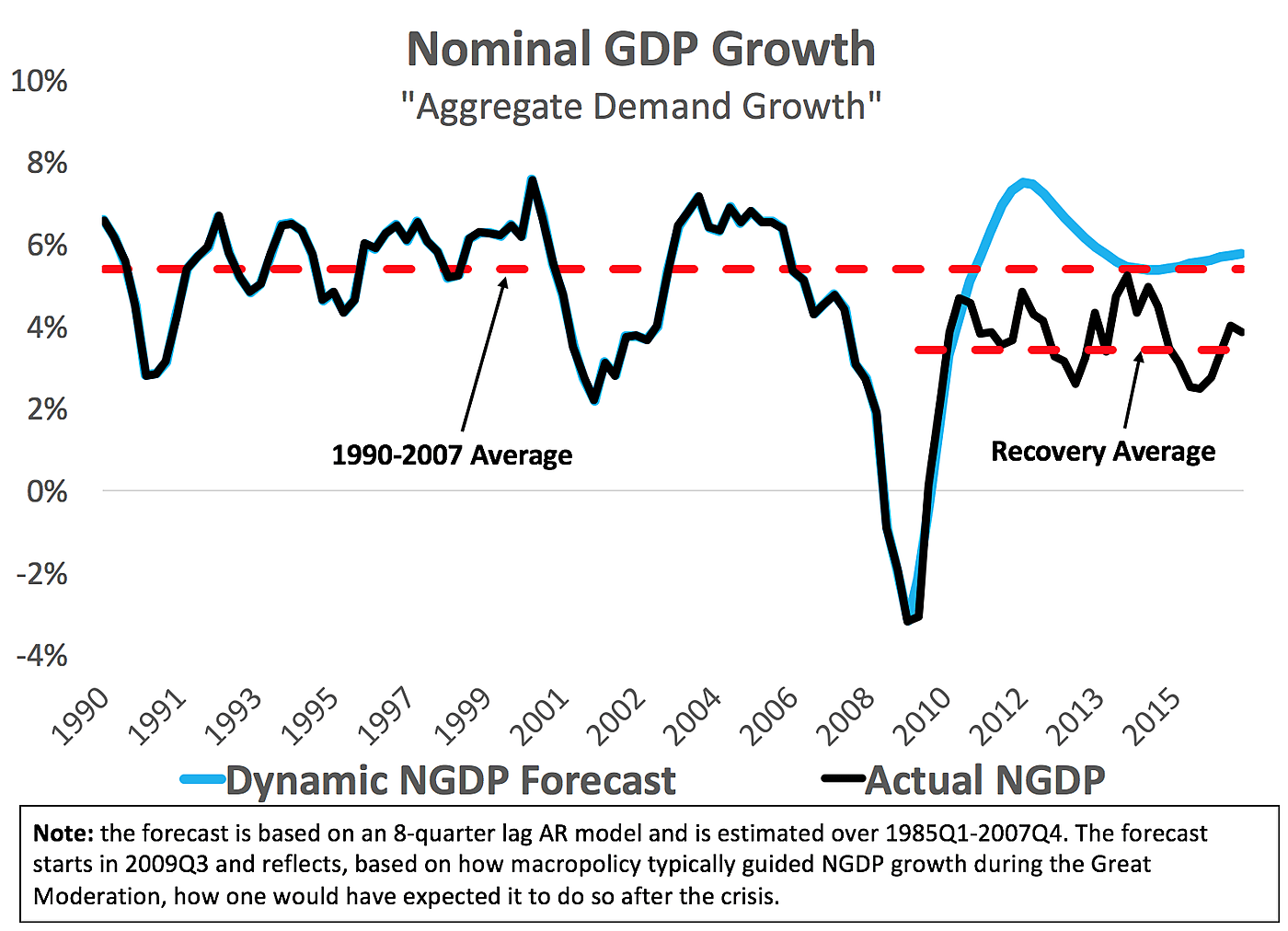

In fact, as David Beckworth pointed out recently, using the chart reproduced below, since the third quarter of 2009 NGDP has grown at an average rate of just 3.4 percent, compared to 5.4 percent between 1990 and 2007 and 5.7 percent for the full “Great Moderation” period of 1985–2007:

According to Beckworth the decline reflects “a monetary regime change” consisting in part of the Fed’s having failed to allow spending to “bounce back at a higher growth rate during the recovery” as it had done in past recessions.

But while explanations that attribute the Fed’s failure to reach its inflation target to slow NGDP growth have the distinct virtue of taking the equation of exchange (MV = Py) seriously (which is more than can be said for some of the others), they still beg the question: why hasn’t the Fed achieved higher NGDP growth?

To observe that it hasn’t done so because it hasn’t been directly targeting NGDP won’t do. After all, a 2 percent inflation target implicitly calls for whatever NGDP growth rate it takes to achieve 2 percent inflation. Arguments to the effect that the Fed has failed to achieve 2 percent inflation because it has failed to achieve 5 percent NGDP growth (or some such number) instead of 3.4 percent growth do no more than state the original question in slightly modified form.

The Regime Change that Matters

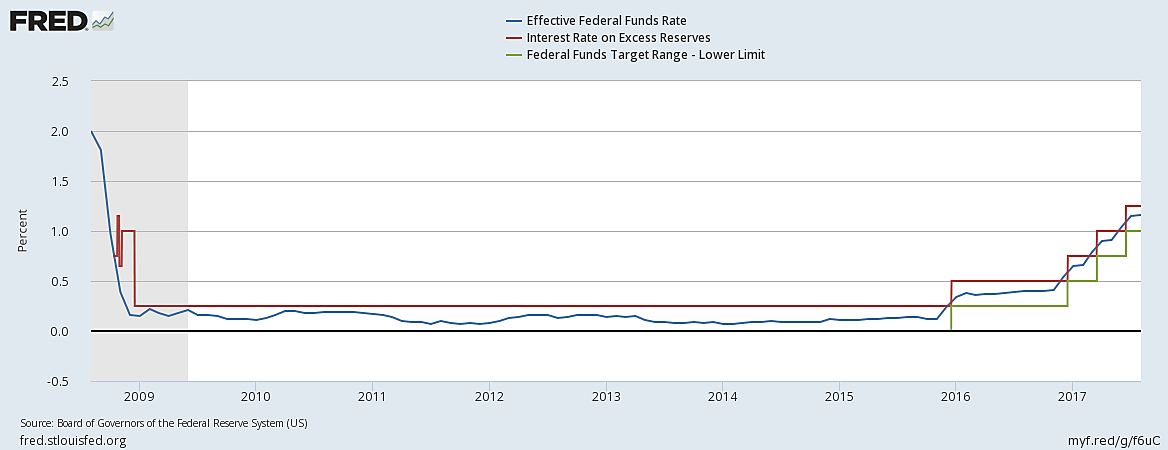

In fingering “regime change” Beckworth gets closer to the truth. Only the regime change that really matters isn’t the shift away from level to rate targeting that he emphasizes. It’s the switch, in October 2008, from the Fed’s conventional monetary control arrangements, with a market-based fed funds target achieved with the help of open-market operations, to its current IOER-based (leaky) “floor system” — in which the fed funds rate is moved up or down by raising the rate of interest the Fed pays on banks’ excess reserves, either alone or together with the rate it offers in its overnight reverse repurchase (ON-RRP) agreements.

What does the Fed’s switch to a floor system have to do with the low inflation and NGDP numbers we’ve been seeing ever since? Bear with me, and I’ll explain.

To do so I must first explain in a bit more detail how a floor system works. In so doing, I’m going to abstract from the role of ON-RRPs, for those aren’t actually part of an orthodox floor system, in which the IOER rate alone serves as the central bank’s policy rate. In the U.S., the situation is complicated by the fact that various GSEs keep balances at the Fed, but aren’t eligible for interest on those balances. Consequently banks and those GSEs can mutually profit by having the GSEs lend their excess Fed balances to the banks for a rate somewhere between the IOER rate and zero. To partially address this “leak” in what would otherwise have been a solid IOER-based federal funds rate floor, the Fed offered the GSEs and some other non-bank financial institutions the opportunity undertake reverse repos with it, thereby establishing a solid ON-RRP subfloor below the leaky IOER-rate floor. This arrangement serves to limit the extent to which the effective fed funds can fall below the IOER, although it still allows it to vary between that rate and the ON-RRP rate, as can be seen in the chart below. Those two rate therefore serve as upper and lower “bounds” of the Federal Reserve’s post-2008 fed funds rate target “range.”

A Floor System Calls for Substantial Excess Reserves

Abstracting, then, from the “leakiness” of the Fed’s IOER-rate floor, and the presence of an ON-RRP rate sub-floor, the basic idea of a floor system is that the interest rate on excess reserves displaces the fed funds rate as the key monetary policy rate. That’s because, in an ideal (leak-free) floor system, banks would neither lend nor borrow federal funds, whether from other banks or from non-bank financial institutions. Instead, they find it more profitable to hold excess reserves. A necessary and sufficient condition for this is that the IOER rate be sufficiently high relative to equivalent private-market rates of interest. In that case, banks will find it more attractive to hold excess reserves than to lend in private overnight markets, including the fed funds market. So long as they accumulate sufficient excess reserves, they can also protect themselves against any need to borrow funds overnight to meet either their net settlement needs or their legal reserve requirements. Of course the banks will find it especially easy to accumulate excess reserves if the Federal Reserves creates large quantities of fresh reserves, as the Fed did through its various rounds of quantitative easing. Still in the long run what matters most for the existence of a floor system is, not that any particular nominal quantity of reserves should be available, but that banks should have a robust demand for excess reserves, as they will only so long as such reserves yield a sufficiently attractive return.

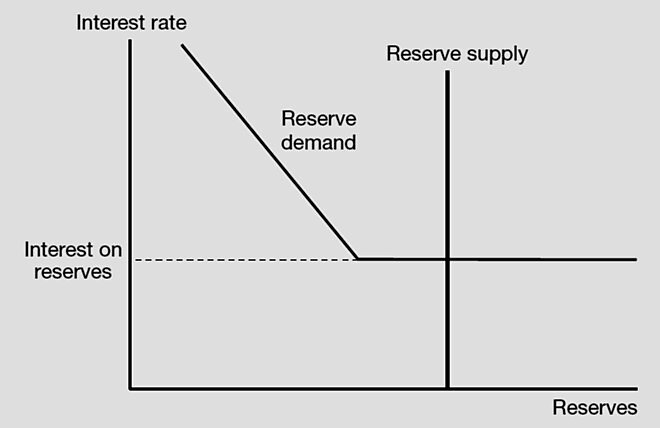

In an orthodox floor system, such as is established when these conditions hold, the market for bank reserves functions as in the diagram below, taken from Marvin Goodfriend’s locus classicus on the subject:

As the diagram shows, so long as banks hold sufficient excess reserves, monetary policy becomes a matter of making desired changes to the IOER rate alone. Through arbitrage those changes will influence other interest rates. Changes in the actual stock of bank reserves, on the other hand, are neither necessary nor sufficient to influence the general state of interest rates. Instead, banks holdings of excess reserves increase and decline in lock-step with shifts in the supply of total reserves, leaving not only interest rates but lending, spending, and the inflation rate largely unchanged.

Whence the Deflationary Bias?

You’re still wondering what all this has to do with the Fed’s persistent undershooting of inflation. Trust me, I’m getting there!

It might appear that the switch from a conventional to a floor system should make no difference in the Fed’s ability to pursue whatever policy it wishes. After all, all that has changed is the mechanism by which the Fed pursues its policy targets, rather than its ability to set and pursue those targets. Whereas before, to loosen (or tighten) policy, the Fed may have had to increase (or reduce) the available supply of bank reserves, now it only has to lower (or increase) the IOER rate. So, why shouldn’t it be able to lower that rate enough to get inflation to 2 percent, or whatever other figure it prefers?

The answer is that, while in principle it could achieve a higher rate of inflation by lowering its IOER rate sufficiently (or, in the actual case, by lowering both its IOER and ON-RRP rates sufficiently), it cannot generally achieve any inflation rate that it wants while also maintaining a floor system. On the contrary: as I’ll explain in a moment, although the masterminds behind the Fed’s turn to a floor system don’t seem to have realized it, maintaining such a system necessarily introduces a deflationary bias in monetary policy.

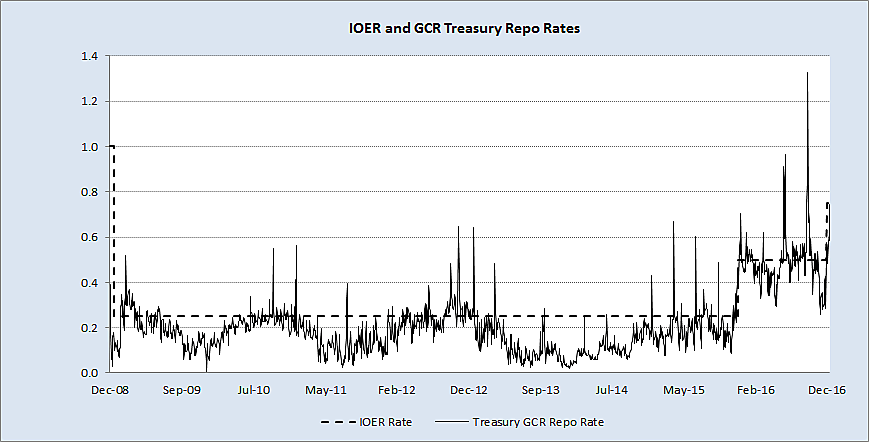

To see why, recall that, to maintain a floor system, the IOER rate has to be high relative to corresponding market rates. Otherwise banks won’t be inclined to accumulate and sit on substantial excess reserves. Instead, they’ll increase their lending in wholesale and other markets that offer them better risk-adjusted returns. To serve as a floor (and forgetting about GSE-based leaks), the IOER rate must be an above-market rate.

That the Fed’s IOER rate has in fact been kept above corresponding market rates is easily shown by comparing it to its closest private-market counterparts. Of those the closest is probably the Depository Trust & Clearing Corporation’s GCF (General Collateral Finance) U.S. Treasury and Agency-Based MBS Repo rate index. The next figure shows how the IOER rate has generally been kept above, and often well above, that comparable market rate:

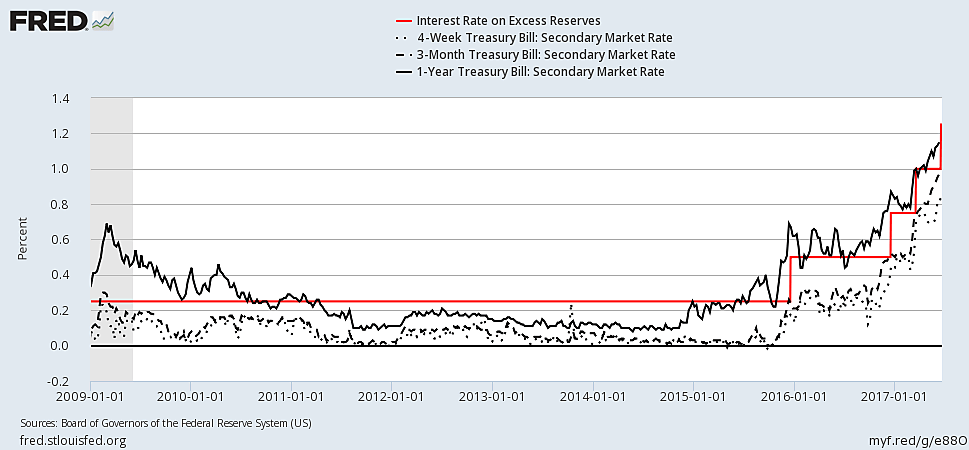

A comparison of the IOER rate and yields on various shorter-term Treasury securities tells a similar story:

As can be seen, whenever market rates have tended to increase, the Fed has made a point of having its IOER rate keep up with those changes. It has done so, moreover, despite the fact that it has persistently fallen short of its inflation target. Clearly the rate adjustments cannot be justified by appeal to the Fed’s desire to stick to that target. They can, on the other hand, be accounted for as inevitable consequences of the Fed’s determination to keep its shiny new (albeit leaky) floor system going.

A Wicksellian Perspective

I’m still not quite done, for I’ve yet to explain in the clearest way possible why a floor system introduces a low inflation bias in monetary policy. Doing that requires that I appeal to Knut Wicksell’s understanding of how an economy’s rate of inflation depends on the relation between its central bank’s chosen policy rate and the economy’s corresponding “natural” rate of interest. According to Wicksell, a policy rate set below its “natural” level will tend to promote inflation, while one set above its natural level will tend to promote deflation.

One can quibble with the details of Wicksell’s argument, as I myself have done by noting that a nation’s inflation rate depends, not just on its central bank’s monetary policy stance, but on the state of economic productivity, among other things. (For this reason I think it better to speak of an above-natural policy rate inevitably leading, not necessarily to deflation or disinflation, but to an excessively low rate of NGDP growth.) The point remains that a central bank that tends to set its policy rate too high will also tend to generate less inflation than it wants.

To see that this is exactly what will happen if a central bank insists on preserving a floor system, imagine that we are back in the pre-2008 monetary control regime, with no IOER and a market-determined fed funds rate. Assume as well that the rate is both on target and at it’s “natural” level — that is, the Fed’s target is consistent with a modest (if not zero) rate of inflation.

Now suppose the Fed decides to switch to a floor system. To do that, it first has to set an IOER rate at least as high as the established fed funds rate, and therefore either at or above the natural funds rate, so as to encourage banks to accumulate excess reserves, in anticipation of boosting the supply of reserves. These steps are needed to get the fed funds market onto the flat portion of the reserve demand schedule shown in Goodfriend’s diagram above. Thenceforth, to stay in the new regime, as natural rates increase the Fed must increase the IOER as well. While a below-natural IOER rate will undermine the floor system by causing banks to shed their excess reserves, an above-natural IOER rate won’t. A permanent floor system is, for this reason, a recipe for monetary over-tightening.

Obviously, if the Fed decides to introduce a floor system at a time when policy is already tight, so that the going fed funds rate is already an above-natural rate, the switch will tend to result in additional over-tightening, since it must involve introducing an IOER rate that’s at least as high as the already excessively high established fed funds rate. Something like this appears, in retrospect, to be what happened in October 2008.

A Missing Piece

My explanation for the Fed’s persistent tendency to undershoot its inflation target is still not quite complete. For it rests on the underlying premise that the Fed is determined, by hook or by crook, to maintain a floor system of monetary control. What proof have I of that?

It is a good question. My answer is, first of all, that the proof lies at least partly in the pudding. For, as I’ve stated, were it not for its determination to keep a floor system in place, it would be difficult to explain the Fed’s insistence upon raising its policy rate despite falling short of its inflation target. Further evidence consists of the Fed’s present normalization plan, which calls for eventual increases in the federal funds rate by close to 175 basis points. So far as Fed officials have indicated, that increase is to be achieved entirely by means of equivalent increases in the IOER rate. In short, if the Fed has any intention of ever returning to its pre-IOER operating system, or to a true “corridor” system in which the IOER rate serves not as an upper but as a lower bound for the fed funds rate, it has given no indication of it. On the contrary: having spoken to several Fed insiders on the matter, I’m assured that the Fed has every intention of sticking to the present system.

Why it should wish to do so is a different matter. I’m pretty sure that part of the reason is that Fed authorities are themselves unaware of the over-tightening bias present in a floor system. They applaud, on the other hand, the fact that a floor system allows them to separately manage interest rates on the one hand and the state of bank liquidity on the other. In recent Congressional testimony,I likened the Fed’s gain in flexibility in a floor system — its being able to set its policy rate however it likes, while altering the supply of bank reserves however it likes — to the gain an automobile owner might secure, in being able to turn the wheel as much as she likes, while also stepping on the gas peddle however much she likes, by shifting from Drive to Neutral. The problem, of course, is that, while the driver seems to have more options, the car no longer gets her where she wants to go.

The Solution

What do you suppose it is? The Fed has to abandon its misguided floor system, the sooner the better, by moving to reduce its IOER rate, instead of increasing it — as it has been planning to do. As the rate falls from above market to below market, the money multiplier will revive; and that revival will, believe you me, prove more than adequate to boost spending enough to get the PCE inflation rate to 2 percent — and beyond. To keep it from getting too high, the Fed will have to plan on more aggressive balance sheet reductions or resort to its Term Deposit Facility or both. All this is difficult, but not impossible. The Fed can certainly do it if it tries. What it can’t do is stick to the present floor system and reliably hit its inflation target.