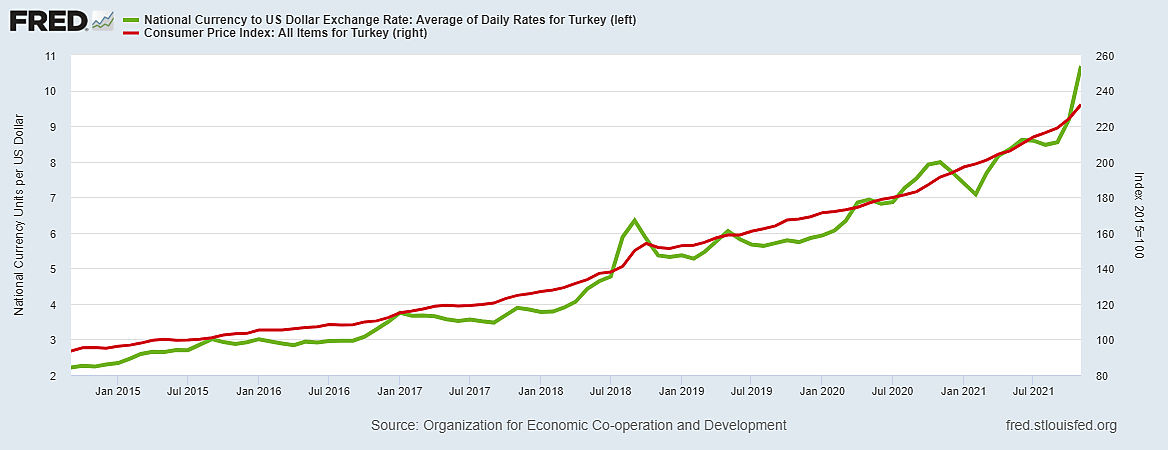

Turkey is at least trying to stabilize exchange rate expectations, though it is not clear if they have a sustainable strategy to do that.

When people at home and abroad lose confidence in a country’s currency, the time-tested ways to stop the inflationary rush to get rid of the shrinking currency are to firmly link the unit of account (Turkish lira) to a more credible currency such as the euro or dollar – preferably through full convertibility (a currency board).

In 1993, the Istanbul Chamber of Commerce invited me to spend a week consulting with Turkish businessmen there and government officials in Ankara on economic policy issues, including the benefits of lower tax rates (which were adopted much later, though in 2020 the top individual rate was raised from 35% to 40%).

What I advised about inflation is briefly summarized in the following section from my presentation in the Spring/Summer 2003 Cato Journal. That paper was, in part, a critique of IMF “advice” (conditions attached to loans) which frequently included currency devaluation and new or higher taxes.

In the current situation, however the recent flight from the Turkish lira appears to have been self-inflicted rather than a result of any strings attached to the $6.4 billion IMF loan on August 24.

Excerpt from “Crisis and Recoveries: Multinational Failures and National Successes” (2003):

In February 2001, U.S. Treasury Secretary Paul O’Neill said, “We fully support the government of Turkey’s actions today to float the Turkish lira.” He predicted this would strengthen “growth and disinflation in Turkey.” Did the Treasury secretary’s advisers imagine the Turkish lira was fixed as it sank from 200,000 to 1.6 million per dollar under various IMF programs since late 1997? Did they suppose Turkey or the IMF thought the lira might suddenly float upward in 2001, and thus contribute to disinflation?

In reality, the Turks have long been star pupils of IMF exchange rate management. If inflation is 40 percent, they devalue by about 50 percent to make sure their exports remain “competitive.” When inflation then rises to 60 percent, they devalue by 70 percent, and so on. Interest rates have to stay above the inflation rate or this game of chasing your tail could slip into hyperinflation. High nominal interest rates ensure that debt service swallows most of the budget, producing a huge nominal deficit that has to be financed. Inflation pushes everyone into high tax brackets, so what is left of the economy moves underground. The deficit cannot be financed by selling bonds because perpetual devaluation comes in endless waves. The central bank ends up printing money to pay the inflated interest on government bonds, which feeds another round of inflation, another devaluation to stay competitive, more inflation, and so on.