Recently, Moody’s Investors Service took some wind from Turkey’s sails, when it declined to upgrade Turkey’s credit rating to investment grade. Moody’s cited external imbalances, along with slowing domestic growth, as factors in its decision. This move is in sharp contrast to the one Fitch made earlier this month, when it upgraded Turkey to investment grade. Moody’s decision not to upgrade Turkey, and its justification, left me somewhat underwhelmed – given how well the Turkish economy has done in recent years.

Since the fall of Lehman Brothers, Turkey’s central bank has employed a so-called unorthodox monetary policy mix. For example, a little over a year ago, it began to allow commercial banks to purchase gold from Turkish citizens and allowed banks to count gold to fulfill their reserve requirements. Incidentally, this was a remarkable success – from 2010–2012, the Turkish banking sector’s precious metal account increased by over 7 billion USD.

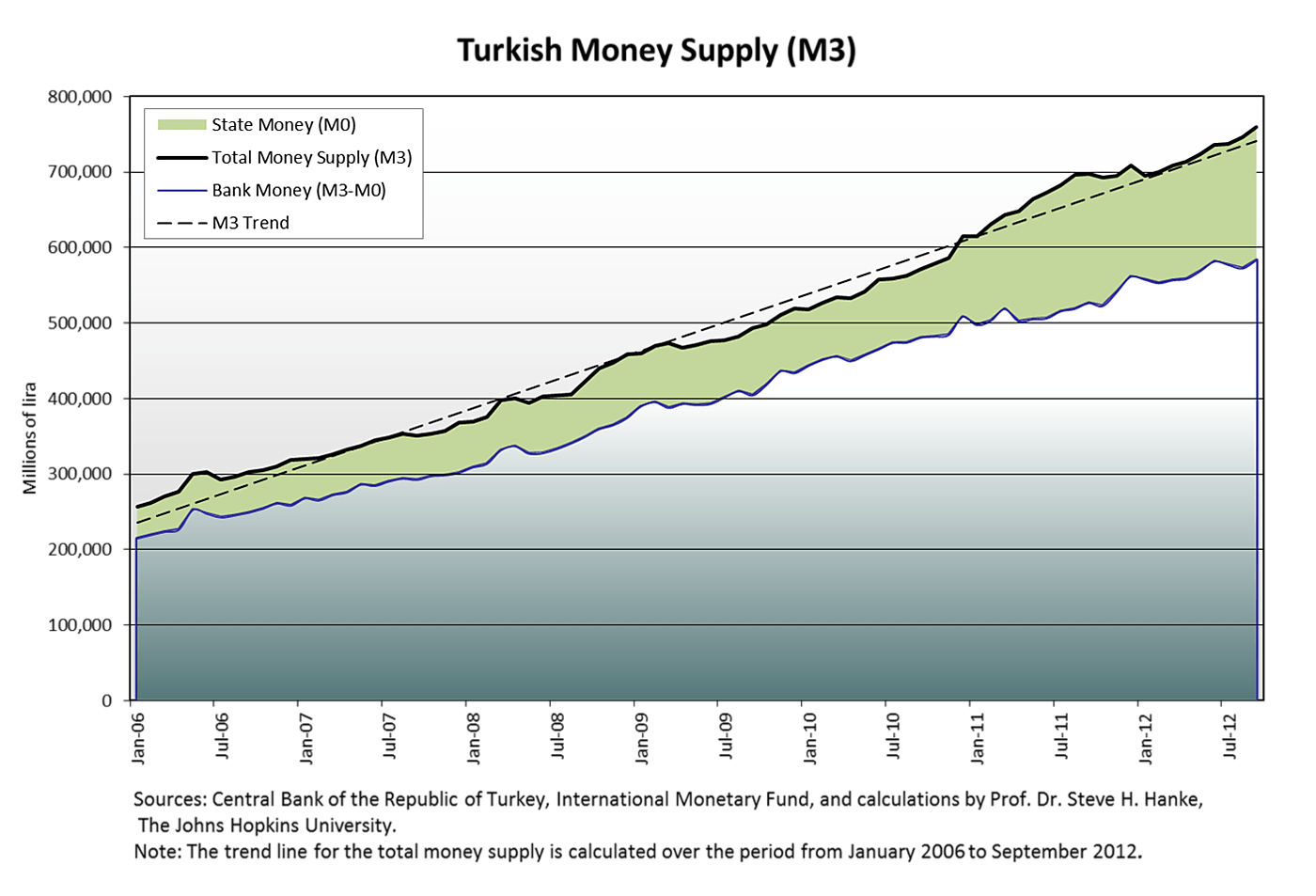

For all the criticism its unconventional monetary policies have garnered, the Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey has, in fact, produced orthodox, golden results. Indeed, as the accompanying chart shows, the central bank has delivered on the only thing that really matters – money.

Turkey’s economic performance has been quite strong (despite some concerns about inflation and its current account deficit) . Turkey’s money supply has been close to the trend level for some time, and it currently stands 2.41% above trend. This positive pattern is similar to that of many Asian countries, who continue to weather the current economic storm better than the West. And, it stands in sharp contrast to the unhealthy economic picture in the United States and Europe – both of which register significant money supply deficiencies.

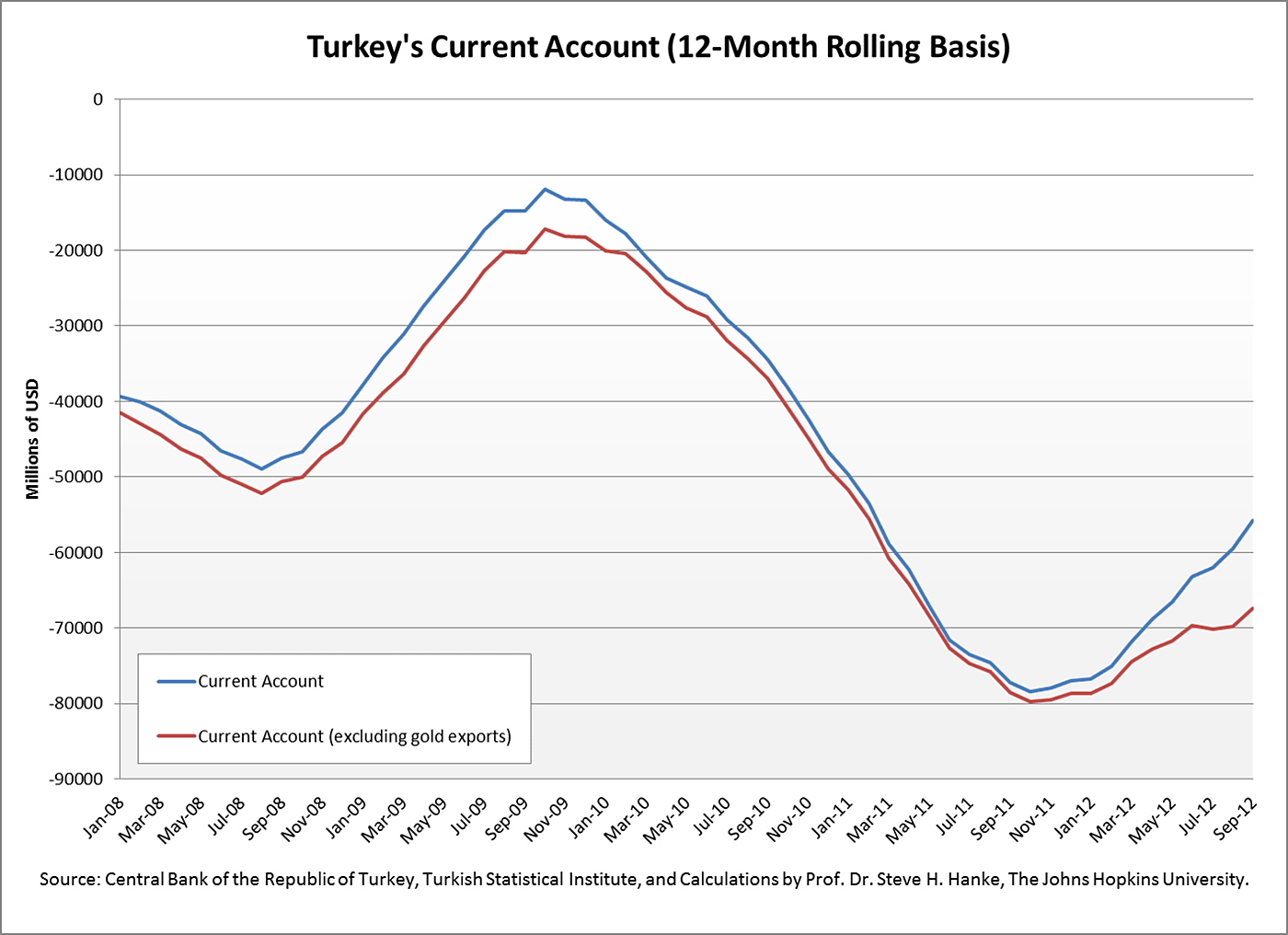

So, why would Moody’s not follow Fitch’s lead and upgrade Turkey to investment grade? To understand this divergence, one should examine Turkey’s recent current account activity. Since late 2011, Turkey’s current account has rebounded somewhat (see the accompanying chart).

But, if gold exports are excluded from the current account (on a 12-month rolling basis), a rather significant 47% of this improvement, from the end of 2011 to September 2012, magically disappears.

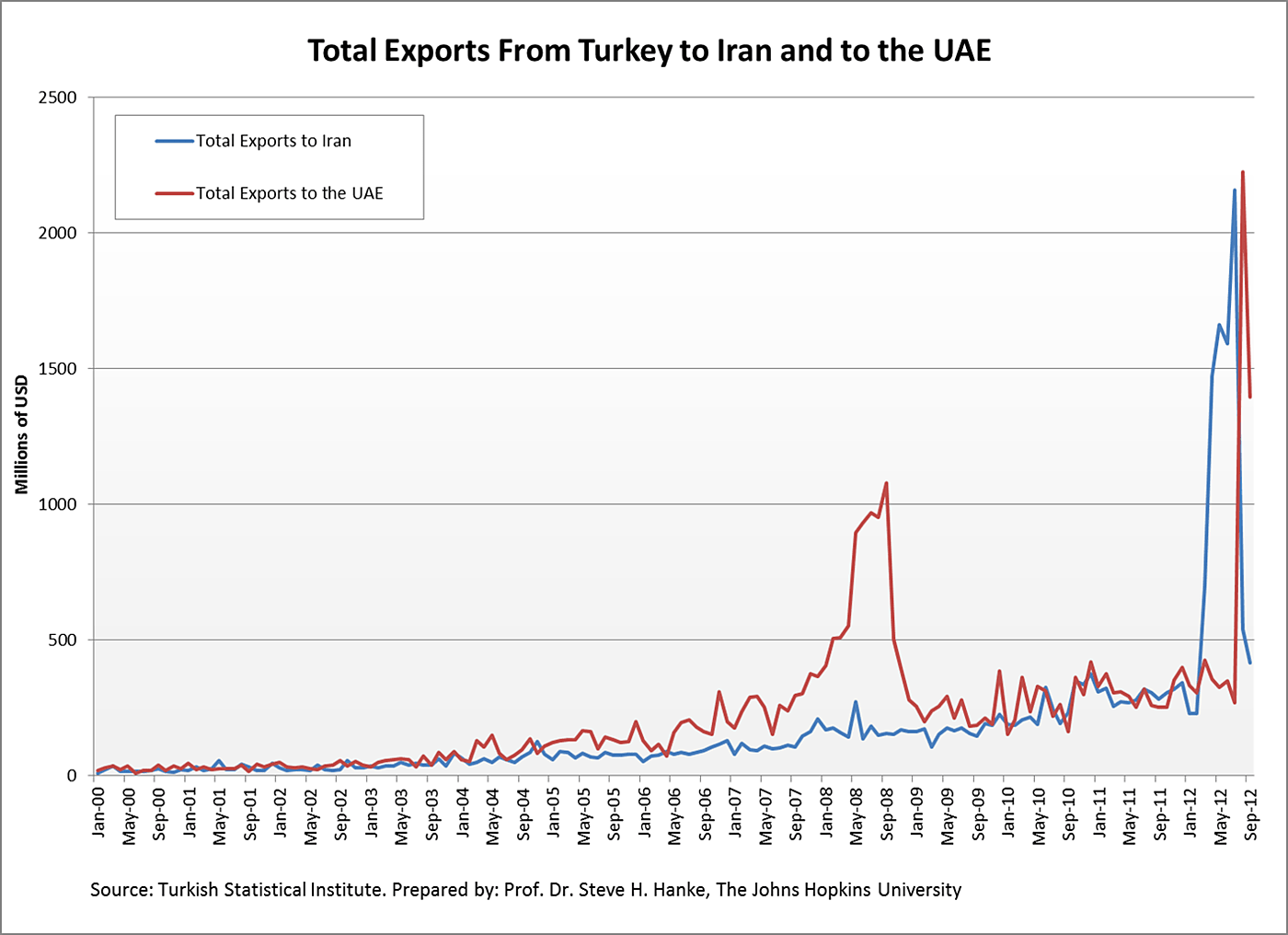

Where is this gold going? Well, a quick look at the accompanying chart shows just how drastically exports to Iran and the UAE have surged this year.

Taken together, the charts indicate that Turkey is exporting gold to Iran, both directly and via the UAE , propping up their current account in the process. This has put Turkey and the UAE in the crosshairs of proponents of anti-Iranian sanctions. Those who beat the sanctions drum are now seeking to impose another round of sanctions, aimed at disrupting programs such as Turkey’s gold-for-natural-gas exchange. This proposal clearly highlights some of the problems associated with sanctions, specifically the unintended costs imposed on the friends of the U.S. and EU in the region. Indeed, Dubai has already taken a hit, with its re-exports falling dramatically as a result of the sanctions.

What is the U.S. to do – go against Turkey, its NATO ally? Believe it or not, some in the Senate are allegedly considering such a wrong-headed move.

If these proposed sanctions are implemented, then Moody’s pessimistic outlook on Turkey may turn out to be not so far from the mark, after all – and Turkey will have no one but its “allies” to blame.