My previous attempts at asking a Trump trade adviser directly about trade policy failed. I’m now going to try another approach: Interpreting something surprising two other Trump advisers said.

Here’s what Wilbur Ross and Peter Navarro wrote recently:

The saddest fact here is that Hillary Clinton doesn’t know the difference between a good trade deal and a bad one. Exhibit A is the Central American Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA-DR).

In her economic speech in Detroit, Clinton bragged that she voted against the one multilateral trade deal that came before the Senate while she was there. That was indeed CAFTA-DR, a multilateral deal involving the U.S. along with Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, and the Dominican Republic.

Here’s what Clinton did not confess to: She was wrong to oppose CAFTA-DR. In 2014, we had a favorable trade in goods balance with the CAFTA-DR countries of $2.7 billion. By 2015, that jumped to $5 billion. This pattern continued in the first half of 2016 with a surplus of $2.4 billion.

Did you catch that? Trump’s trade advisers are praising a U.S. trade agreement. That doesn’t sound very Trump-like, as Trump has been saying NAFTA is a “disaster” and has been calling the Trans Pacific Partnership (TPP) the “rape” of our country.

So why do they like the CAFTA-DR? Because in 2014 (9 years after the deal went into effect), there was a U.S. surplus in trade in goods with the various members of CAFTA-DR. That by itself tells them it was a good deal.

They follow this up with their typical criticism of NAFTA and the US-Korea FTA, complaining that these agreements led to a trade deficit:

Now what about the very poorly negotiated trade deals Hillary Clinton did support? Take NAFTA, which she lobbied for and her husband, former President Bill Clinton, signed in 1993. At the time, our trade in goods with Mexico was roughly in balance, with a small surplus of $1.7 billion. Today, we run a trade deficit in goods of roughly $60 billion — an astonishing leap.

…

NAFTA is hardly a bad trade deal outlier in the Clinton oeuvre. As Secretary of State, Hillary Clinton helped draft the South Korea Bilateral Agreement, describing it as “cutting edge.” She was right. It cut 75,000 American jobs, according to the EPI, rather than the 70,000 gain promised by the White House. Meanwhile, our trade deficit with South Korea has doubled.

So the argument seems to be this: There are good trade agreements that lead to trade surpluses and bad trade agreements that lead to trade deficits. A good negotiator can get you an agreement with a surplus; with bad negotiators, you will end up with a deficit.

In reality, this is complete nonsense. These agreements were all negotiated by basically the same people (the U.S. Trade Representative’s Office), and they all say basically the same thing: They all lower tariffs; they all open services and procurement markets to some degree; they all protect intellectual property; and they all have rules on investor protection. There wasn’t some tricky maneuver the U.S. trade negotiators carried out it in the CAFTA-DR context to get a trade surplus, but forgot to use in the other trade agreements.

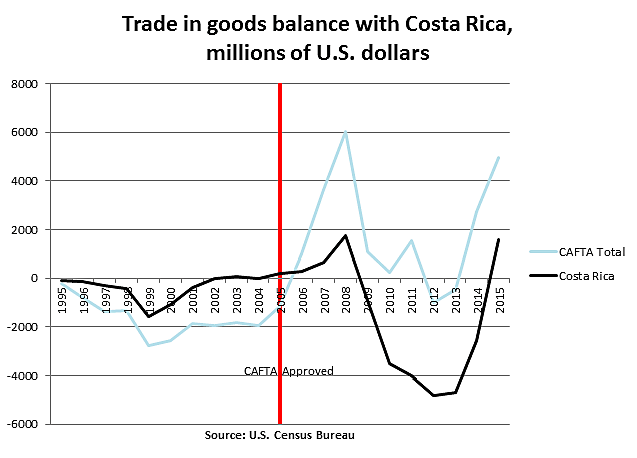

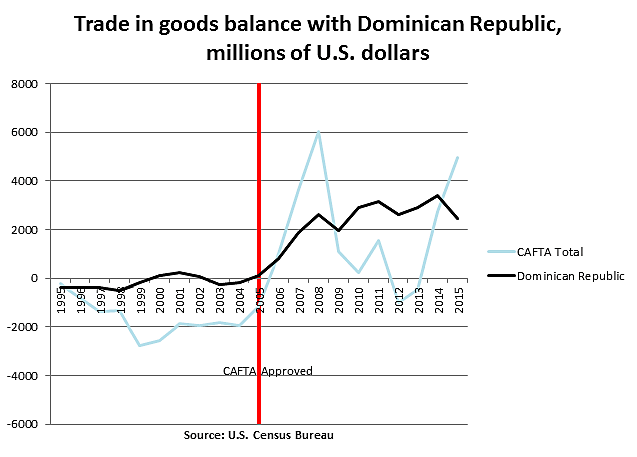

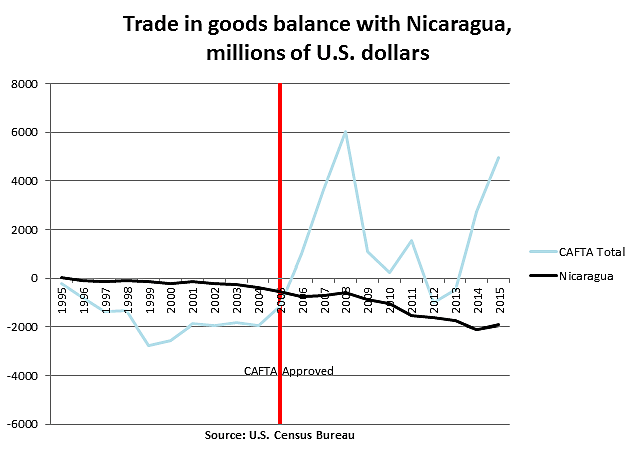

So why the variation in trade flows between agreements? Well, it’s complicated. These trade numbers actually fluctuate quite a bit from year to year. See below for tables showing the U.S. trade balance over the years with several CAFTA-DR countries:

There are a lot of reasons for these fluctuations. Among other things, there are overall trends in the global economy and in specific national economies; and there are the decisions of private actors operating in the marketplace (it is these actors who are the ones actually doing the trading), which affect particular sectors over time. Thus, citing a trade surplus with CAFTA-DR countries — especially when it focuses on only the brief period 2014–2016 — as a reason for the success of the agreement vastly oversimplifies the impact of trade agreements on trade flows. Again, it is not the skill of the CAFTA-DR negotiators vs. the incompetence of the NAFTA or US-Korea FTA negotiators that led to the different results here. As noted, it was basically the same people on each. This is not like baseball. Trade negotiators do not have an off year and negotiate a bad trade agreement one year, but then come back a couple years later and have a career year by negotiating a good trade agreement.

But Trump’s advisers don’t realize that, probably because they don’t really know much about the substantive details of trade agreement. They are simply looking at U.S. trade deficits or surpluses that arise after the fact, which generally matter very little (as my colleague Dan Ikenson has explained), and certainly don’t matter much at all in the context of trade between the U.S. and individual countries.