Do you drive an imported car or one made here by a foreign-owned company? If so, you may be a serious threat to national security – if a long-awaited report from the Trump administration is to be believed.

No, really.

Last week, the Department of Commerce finally released its report on U.S. imports of automobiles and certain automotive parts, as part of the Trump administration’s 2018 investigation pursuant to Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962. While the report was submitted to the president on February 17, 2019, it was not published in the Federal Register, as the law requires, because the statute does not provide a deadline for doing so – one of many glaring loopholes in the law that relieve the Executive Branch of its accountability to Congress and the public for any actions (tariffs, quotas, etc.) taken thereunder. The Biden administration’s move to release the report is welcome, and we hope that they will also release the four remaining reports (uranium ore, titanium sponge, transformers and their components, and vanadium) in the near future.

As we wrote in a paper earlier this year, however, even the release of all remaining reports would be insufficient when it comes to righting Section 232’s wrongs. The autos report’s history, findings, and implications – and a recent court case on Section 232 – make this clear.

The Report’s History

The autos report’s history demonstrates one of the law’s biggest procedural weaknesses: it allows the Executive Branch to keep Section 232 investigation findings secret indefinitely, even after the president has taken action and Congress has demanded they be released. After the report was submitted to President Trump, he agreed with the findings that auto imports threatened U.S. national security in May 2019. However, instead of imposing tariffs (as he did in the case of steel and aluminum), he directed the U.S. Trade Representative to engage in negotiations with the European Union and Japan, but continued to threaten the application of a 25 percent tariff if a satisfactory deal could not be reached. Given the fact that negotiations proceeded with two close allies, it was unclear how imports from them could be considered a national security threat. Without access to the report that spells out the administration’s reasoning, the best we could do was guess.

As we explained in our paper, the Trump administration even openly defied a new law—passed almost six months after the autos report was completed—requiring the Commerce Department to release it:

The publication deadline was attached to a spending bill, so Trump had little choice but to sign the measure into law. However, just before the congressional deadline expired, the Trump administration claimed that the Commerce Department’s report was protected from disclosure while the president pursued open‐ended trade talks….

The administration claimed that as long as those negotiations were ongoing, the report was protected by executive privilege, which empowers the president to withhold information from the other branches of government. In particular, the Office of Legal Counsel argued that the secretary of commerce’s report “is a quintessential privileged presidential communication” that includes advice to the president from his cabinet and is “protected by the deliberative process component of executive privilege, because it reflects a recommendation made in connection with deliberations over the President’s final decision.” Furthermore, the Office of Legal Counsel argued that disclosure “could compromise the United States’ position in ongoing international negotiations” (i.e., those with Japan and the EU).

As we explain in the paper, both OLC claims were questionable (at best). Now that the report has been released, we see that its findings are similarly dubious and thus demonstrate the persistent problems with the application of Section 232 as a tool to address trade concerns.

The Report’s Findings

The autos report fails to provide both a clear national security justification — relying instead on vague language and an overly broad interpretation of the statute — and evidence for its fantastical claims. For example—

Everything’s a national security threat.

Section 232 authorizes the president to take actions, such as imposing tariffs, against imports deemed to be a threat to “national security.” However, the statute lacks an objective definition of “national security,” essentially permitting anything to be considered a threat, and the Commerce Department took full advantage of this ambiguity in the autos report. In particular, the Department found that “the impact of excessive imports on the domestic automobile and automobile parts industry and the serious effects resulting from the consequent displacement of production in the United States is causing a ‘weakening of our internal economy [that] may impair the national security’ as set forth in section 232.” While it is true that the United States faces international competition in the automotive market, there is no reasonable evidence provided as to what “excessive imports” means or how it might amount to a national security threat. Looking at the arguments presented in the report, the veracity of the Trump administration’s claims on the threat of auto imports is in serious doubt. It also serves as a warning for the continued use of Section 232 absent significant reforms to rein in presidential abuse.

A research and development conspiracy?

The report’s main justification for recommending that automotive imports be restrained is that the research and development generated by the American-owned (i.e., not foreign nameplate automakers operating in the United States and employing thousands of Americans in their factories and labs) auto industry is crucial for U.S. national defense and now at “serious risk as imports continue to displace American-owned production.” However, there appears to be no data provided on historical trends in R&D investment in the United States, so as to establish a clear downward trend (whether for “American-owned” firms or more broadly). If the Secretary of Commerce is going to argue that tariffs are needed to stop troubling trends in automotive R&D in the United States, these data should feature prominently in both the report’s narrative text and charts. They (quite tellingly) do not. Instead, the report provides only a snapshot (2017 data) of U.S. and global R&D activity and a red herring claim that “the share of global R&D investments in the automotive sector attributable to the United States has significantly declined and, today, the share of R&D conducted by American- owned companies is a fraction of the share conducted by foreign competitors.” (The latter tells us nothing about U.S. R&D spending, which could be way up in recent years yet smaller as a share of global R&D spending if other automakers have spent even more.)

It is equally difficult to connect the dots on why only “American-owned” facilities and investments in the United States matter for U.S. defensive capabilities. The main argument provided in the report is that:

while the U.S. military presently benefits from R&D investments by both American-owned and foreign-owned companies in the United States, it is important to underscore that, in the time of national emergency, foreign-owned subsidiaries may not be willing or able to continue their R&D collaboration with the U.S. Government. Nor would it be logical to expect foreign R&D enterprises in the United States to share their research and patented technology with American-owned competitors.

Given that these “foreign-owned” facilities are subsidiaries of companies located in strong U.S. ally countries (e.g., Germany, Japan, and South Korea), that they mainly employ American workers, and that the U.S. military could (heaven forbid) compel compliance in times of war or “crisis,” the Commerce Department’s claims are both ridiculous and offensive. Indeed, our most recent national crisis – combatting the COVID-19 pandemic – has featured tremendous collaboration among multinational manufacturers and governments around the world. The type of “crisis” that would thwart such cooperation exists only in the minds of conspiracy theorists, not national security experts.

The real “threat” is foreign competition for certain U.S. automakers and workers.

While the main claim for using Section 232 to restrict imports appears to rest on the threat to U.S. R&D, the real concern seems to be a fear of foreign competition:

imports of automobiles and certain automobile parts are impairing the strength of American-owned firms in the automotive sector – in terms of both production and revenue needed for R&D investments – and improving the conditions for such firms is necessary to enable the development of technologies needed for our national security requirements.

In fact, the report highlights the troubling development of affordable automobiles and automobile parts, which threaten to displace more costly U.S. production:

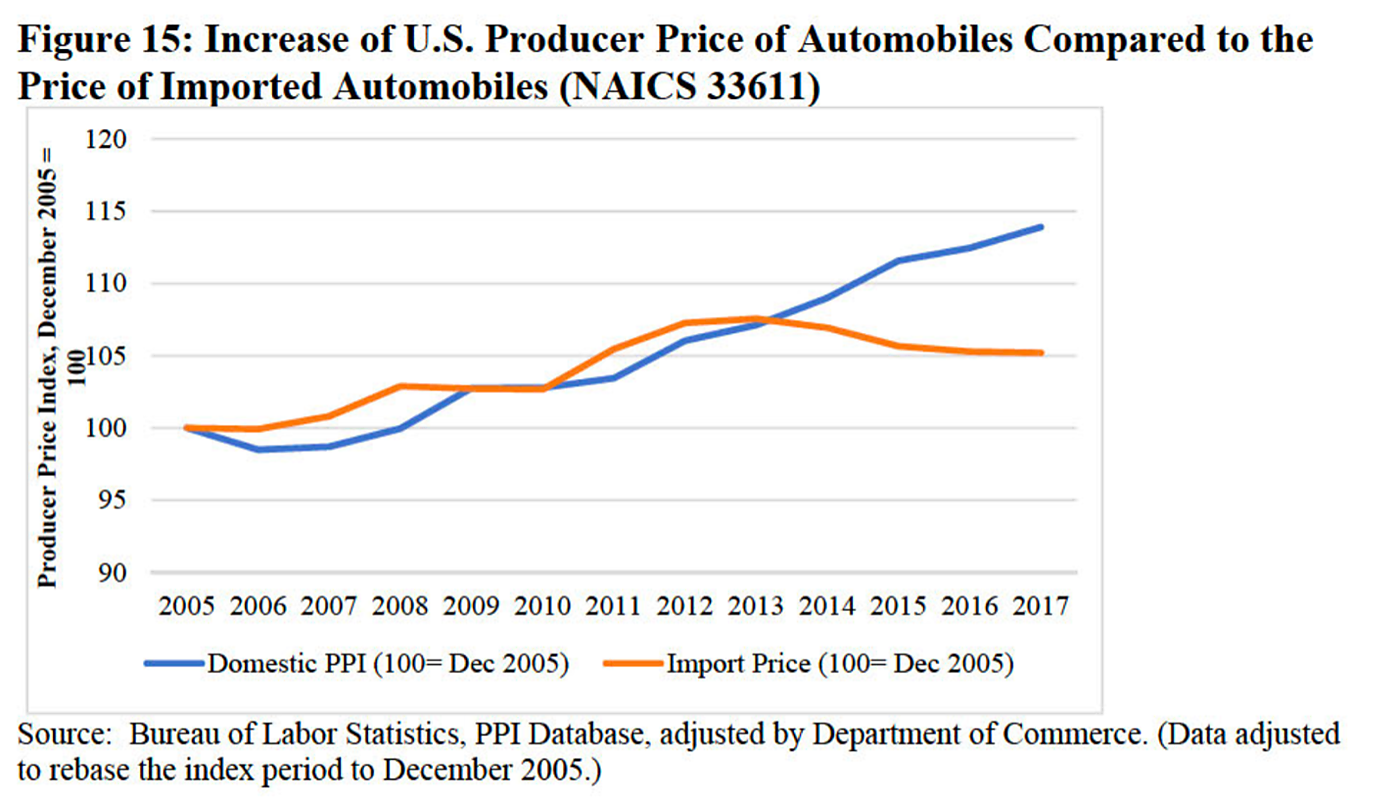

The slow growth of U.S. prices for automobiles is also attributable to the low prices of foreign imports. As shown in Figure 15, since 2005, the average prices of a domestically produced automobile in the United States increased by 14 percent compared to a 5 percent increase in the average price of imported automobiles….In short, imported automobiles have prevented American-owned automobile producers from increasing sales prices. [Figure below].

That American producers and consumers would choose more affordable foreign options when purchasing parts or vehicles is surely a threat to the country!

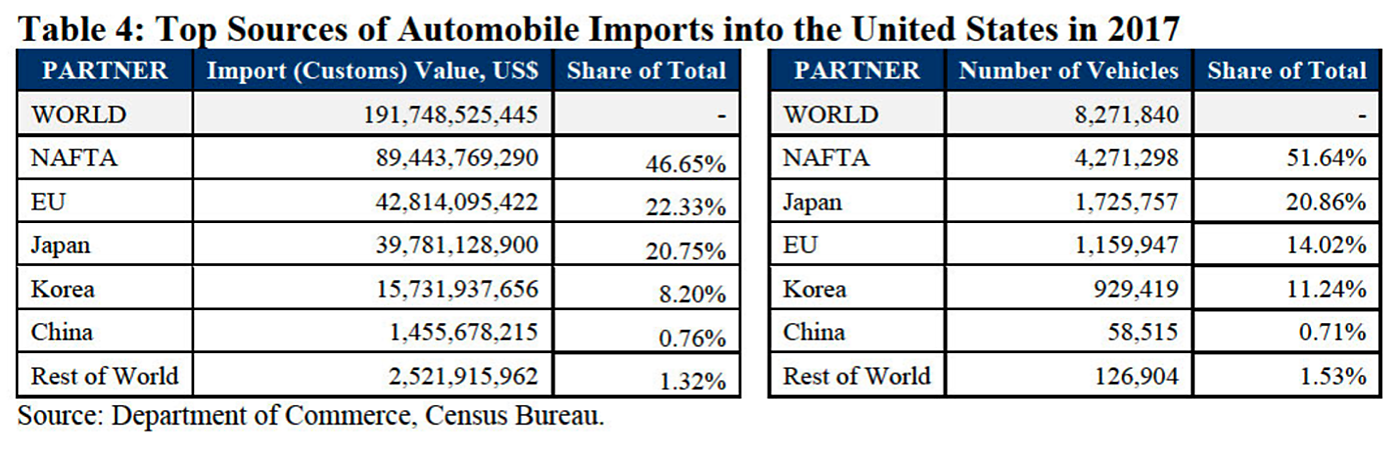

Jokes aside, the report doesn’t provide a more substantive reason to think that automotive imports might pose a national security threat. Indeed, the report finds that the suppliers of and investors in the U.S. automotive market “largely come from allies of the United States” like Mexico, Japan, Germany, and South Korea. Notably, our NAFTA partners, Canada and Mexico, account for 46 percent of the total share of imports, with the EU as a whole coming in second place at 22 percent. Canada’s industrial base is incorporated into U.S. defense planning by law, so it’s hard to see how imports from Canada are a threat. Mexico’s auto sector is highly integrated with the U.S. sector (and its economic performance generally tracks ours), so it is difficult to imagine what incentive Mexico would have to disrupt the automotive supply chain, even in times of crisis.

Furthermore, the relocation of some automotive producers to Mexico (via NAFTA) has led to a more competitive North American auto sector, which rivals European and Asian supply chains. And since Mexico has a trade agreement with the European Union and the United States does not, it also provides American-owned producers with an important opportunity to sell into that large market duty-free.

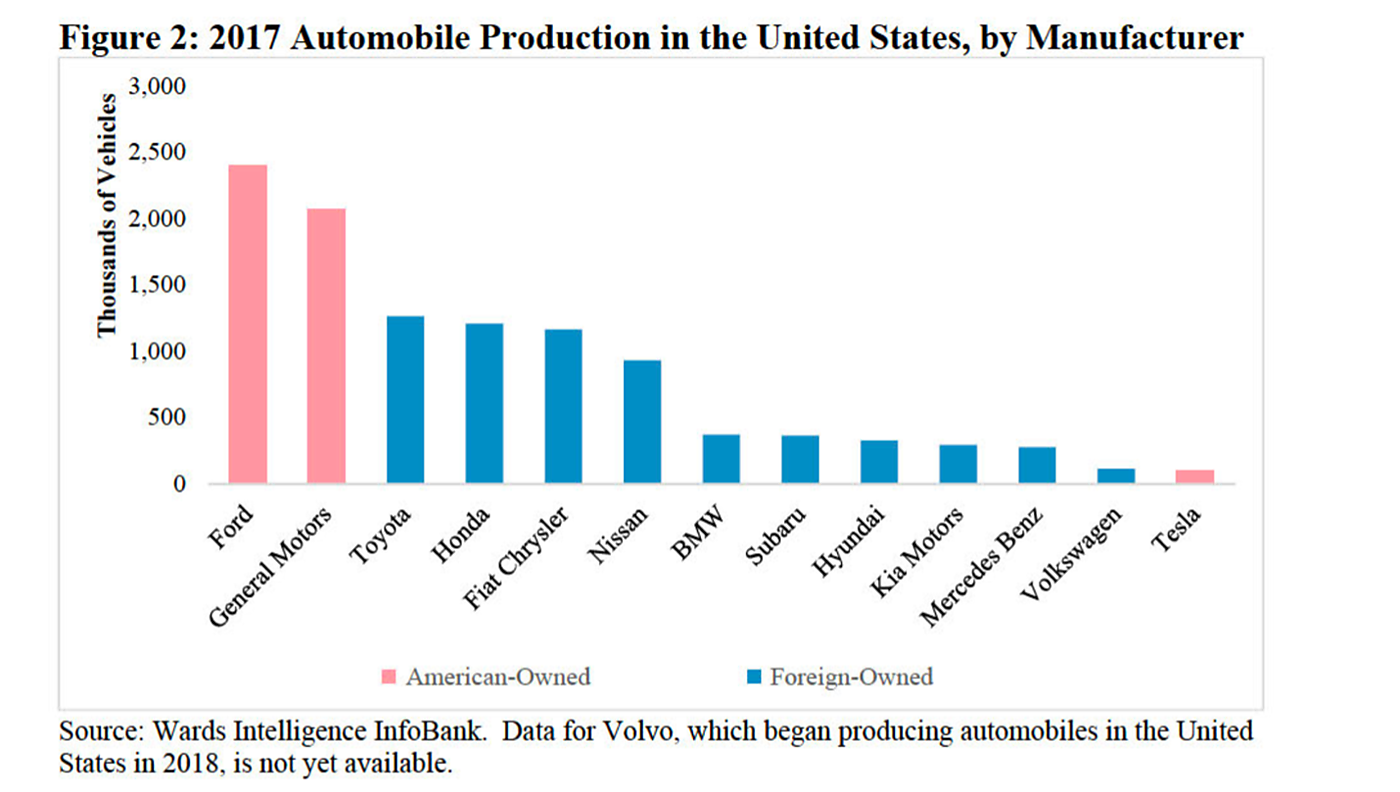

Finally, low-cost imports often benefit the numerous foreign-owned automakers that have facilities here (e.g. by diversifying their offerings or supplying parts), further complicating the administration’s anti-import case (the following figure comes directly from the report):

When these companies invest in the United States, they not only create jobs and generate economic activity but also provide knowledge and skills to American employees that might not be available otherwise. Indeed, research shows that U.S. affiliates of foreign multinationals spend hundreds of billions of dollars per year in the United States on R&D and capital expenditures, and that foreign parent companies typically improve not only their U.S. subsidiaries, but also the domestic companies and communities in which they’re located.

Some national security threat.

Reform is needed

The release of the 232 autos report, while welcome, also serves as a reminder of the urgent need to reform the statute so that future abuses of the law are limited. Section 232 perfectly exemplifies the perils of giving the president too much discretion in applying the law without adequate congressional oversight. The Trump administration was particularly unconcerned with even following basic requirements of the law—failing to publish the reports in five of the eight investigations it initiated (four remain unpublished as of today). But this approach worked to the administration’s advantage, and allowed them to pursue their favorite trade strategy—an overhanging threat of retaliation forcing our trading partners to the negotiating table. Without evidence of the actual threat posed by imports, the administration was offered cover for ongoing negotiations with no end in sight.

In fact, as Senator Pat Toomey (R‑PA) stated in a recent press release “A quick glance confirms what we expected: The justification for these tariffs was so entirely unfounded that even the authors were too embarrassed to let it see the light of day.” Our brief analysis above reveals some of the report’s flaws, but there are many (many) more. Congress now has more than enough evidence of the need for Section 232 reform, and should take action to reassert its power.

Congress will have to take the lead here because, as we’ve noted previously, U.S. courts won’t. Indeed, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit just reversed one of the few checks on the President’s Section 232 powers that the Court of International Trade has asserted (a narrow ruling that voided President Trump’s action to increase, without a new investigation, tariffs on Turkish steel outside the stipulated 90‐day period for presidential action). Should that ruling hold, the president would have essentially no checks on his authority to restrict imports on “national security” grounds, no matter how absurd.

And if you don’t believe us, then read the autos report for yourself.