Cryptocurrencies seem to be on the minds of every government official. Politicians, central bankers, and regulatory heads continue to call for new regulations. However, the design of those regulations is surrounded with uncertainty––an uncertainty that is partly due to the novel nature of cryptocurrencies themselves. If impending regulations are to avoid crushing the technology, that novel nature must be better acknowledged. To that end, government officials should be careful to recognize when they are solely trying to place cryptocurrencies under existing categories––as if regulation is the default condition––instead of addressing the question of what benefit regulation might have.

Decisions, Decisions, Decisions

Chris Brummer argued at the first installment of the Cato Institute’s Center for Monetary and Financial Alternatives’ (CMFA’s) event series on cryptocurrency regulation that regulators traditionally face a trilemma. They must decide between (1) achieving market integrity, (2) enabling innovation, and (3) establishing clear rules. Brummer argued that regulators, at best, only get to choose two of these three options.

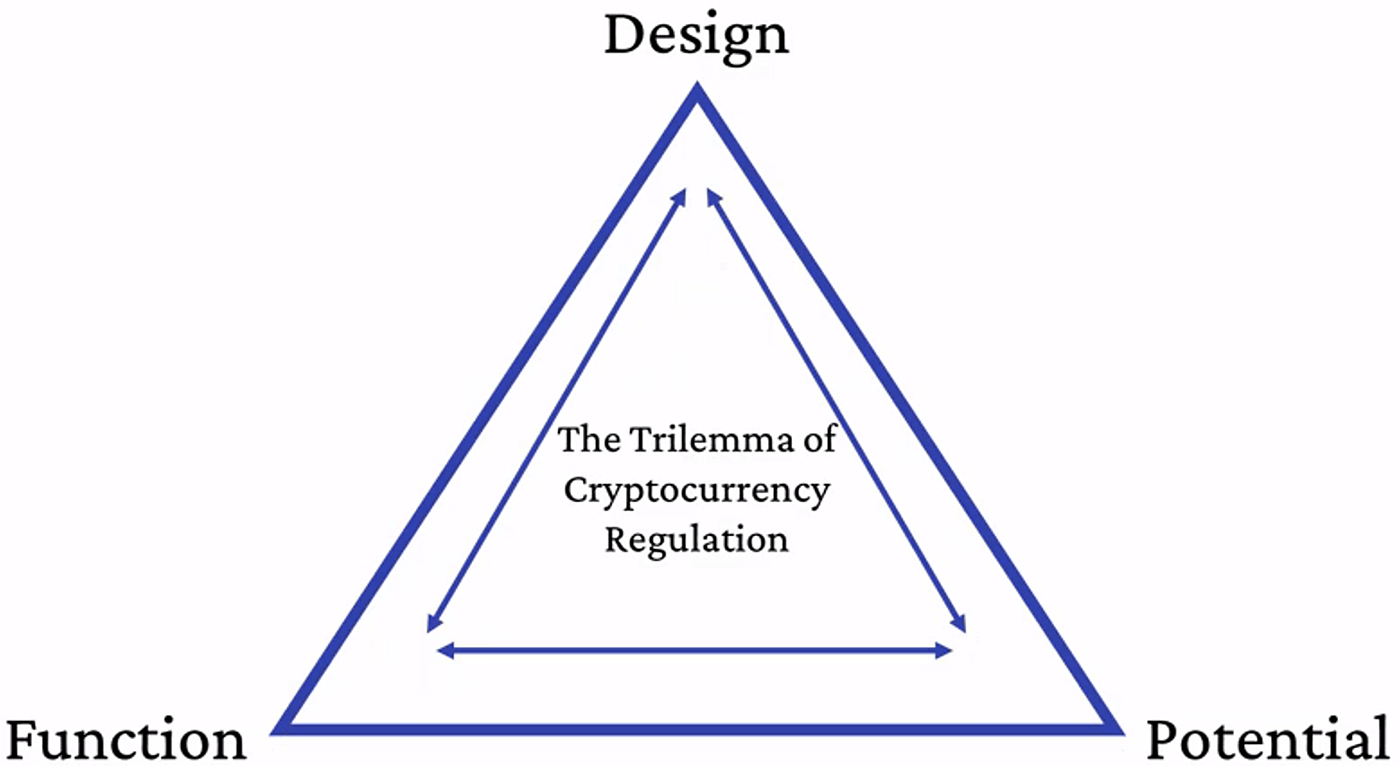

While regulators might face the trilemma that Brummer described when they consider a new product or service, cryptocurrencies are so novel that they require regulators to recognize another trilemma. Namely, regulators must decide between regulating cryptocurrencies as (1) what they were designed to be, (2) how they currently function, or (3) what they have the potential to be. Yet it’s through this lens that it becomes clear that cryptocurrencies rarely fall neatly into any one form.

Figure 1. The trilemma of cryptocurrency regulation

Regulation by Design

What cryptocurrencies were largely designed to be is quite clear from the name: currencies. If taken as described, regulation-by-design would entail regulating bitcoin (and similar endeavors) as a currency. However, the announcements made at their respective launches provide a deeper insight. Consider the Bitcoin Whitepaper, which Satoshi Nakamoto famously introduced by writing, “I’ve been working on a new electronic cash system that’s fully peer-to-peer, with no trusted third party.”

Thus, regulation-by-design is not as simple as putting bitcoin under existing currency regulations. Because bitcoin is decentralized (it has “no trusted third party”), many existing currency regulations would fail––if for no other reason––due to their premise on the third-party doctrine. As evident by the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, blindly assigning existing currency (and securities) regulations to cryptocurrencies can quickly create insurmountable problems.

However, regulation-by-design faces another problem: some cryptocurrencies were designed to be much more than just currencies. For example, Ethereum was designed to be a currency as well as a foundation for other applications. These applications include financial tools like loans and crowdfunding, as well as social platforms like games and social media. Unlike U.S. dollars, Ethereum offers a package deal. Therefore, regulation-by-design would entail treating it both as a currency and a platform––a difficult endeavor for regulators trying to place cryptocurrencies neatly under existing rules.

Regulation-by-design might appear to be the clearest approach for regulators, given one need only reference the stated intent of the cryptocurrency being considered. Yet even if regulators were able to account for the decentralization and the packaged services perfectly, regulation-by-design fails to account for the rapid pace of innovation that has been exhibited in this industry. At best, regulations would no longer apply as products evolve. At worst, regulations would prevent that evolution from taking place.

Christine Lagarde, President of the European Central Bank, expressed her own concern about the innovation in the industry when she said, “[Cryptocurrencies] need to be regulated with oversight that corresponds to the business that they are actually conducting irrespective of how they name themselves.” To that end, rather than regulation-by-design, Lagarde calls for regulation-by-function.

Regulation by Function

What cryptocurrencies function as in practice is not always clear because it is a result of their design and the way consumers perceive them. The key condition with this approach is that one must seek to regulate-by-function, not by assumption. That condition requires looking at actual human behavior to see how consumers and producers are using cryptocurrencies on a daily basis. In other words, it involves going beyond viral memes to find out what people are actually doing with the cryptocurrencies they hold.

Such a process would require asking questions like: are people making regular purchases with cryptocurrencies? What types of purchases are they making? Or, are they only holding them? How long are people holding them? Or, are they primarily using cryptocurrencies for something else entirely?

Representative Paul Gosar’s (R‑AZ) bill, the Crypto-Currency Act of 2020, offers a clear example of trying to address cryptocurrencies through regulation-by-function. The bill sets out separate definitions for crypto-commodities, crypto-currencies, and crypto-securities. In doing so, it assigns the relevant regulators to the appropriate categories. However, the bill also showcases the difficulty in regulation-by-function as it fails to consider how a particular cryptocurrency might have features of all three terms. If enough of the population uses the same cryptocurrency for different ends, it could appear to be very different things at the same moment.

More so, there’s another issue to consider: change. What the market appears to be today is different from what it appeared to be yesterday and different from what it will likely appear to be tomorrow. Much like how regulation-by-design risks preventing further evolution beyond the original intent of a cryptocurrency, regulation-by-function risks freezing them in their current state. Therefore, it might be more appropriate to instead regulate cryptocurrencies in terms of their potential.

Regulation by Potential

What cryptocurrencies have the potential to be is likely the hardest question of all to address. Crystal balls aside, the technology is still young. It often feels like new applications are being found each day.

In the worst of lights, an overzealous regulation-by-potential approach runs the risk of picking winners and losers among competitors and technology. An example of which came when Senator Patrick Toomey (R‑PA) asked why the President’s Working Group suggested that all stablecoins should be regulated the same way and issued only by banks. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen responded, “Well, they all have the potential to be used as a means of payment regardless of how they are used when they are introduced.”

Secretary Yellen is right that stablecoins have the potential to be used as a generally accepted medium of exchange, but the President’s Working Group’s proposal effectively picks the banking industry––a largely absent player in the growth of stablecoins––as a winner and protects them from the possibility of external competition. In that light, it’s clear that this approach would be a mistake. However, regulation-by-potential could be viewed another way.

In the best of lights, regulation-by-potential would entail a light-touch approach to leave room to grow and experiment. Rather than employ strict guardrails, this approach could provide the latitude necessary to carve a new path, free from the constraints of distorted definitions. However, in practice, regulators do not adhere to light-touch approaches. Rather, the history of regulation is often one of mission creep with each bump in the road leading to an ever-expanding state. The journey of American financial markets through the Bank Secrecy Act (1970), the PATRIOT Act (2001), and then the Dodd-Frank Act (2010) is only one such example.

So, unfortunately, even in the best of lights, it seems regulation-by-potential is not the right approach either. In fact, it seems that none of these approaches offer an appropriate path forward. However, that is probably because there is a fatal flaw that has been nested in the background of all three approaches.

Leaving the Triangle Behind

When government officials look through the lens of the trilemma of cryptocurrency regulation, they assume cryptocurrencies are something to be neatly categorized, filed with their respective agencies, and regulated. But cryptocurrencies rarely fall neatly into any one form. As discussed above, cryptocurrencies may have emerged as an alternative to the dollar, but they offer so much more. And there comes a point where one must recognize that a square peg is not going to fit into a triangular hole, no matter the angle one looks at it.

Rather than jump through hoops to answer what cryptocurrencies can be labeled as, government officials should instead try to answer another question: Why do cryptocurrencies need to be regulated at all? If there is going to be regulation, it should only be to the extent that there is some market failure. To that end, government officials should look to Norbert Michel and Jennifer Schulp’s paper, A Simple Proposal for Regulating Stablecoins. Rather than try to categorize stablecoins through the lens of the trilemma, Michel and Schulp propose simply requiring clear disclosures and basic collateral requirements. In doing so, they are answering the only question that matters: if stablecoins need to be regulated at all, it should only be to the extent that it allows consumers to make informed decisions about their risks.

Conclusion

At the second installment of the CMFA’s crypto-regulation series, Jai Massari said one of the reasons it is so difficult to address cryptocurrencies is because cryptocurrencies do not take any one form. Senator Toomey made a similar point during his questions to Secretary Yellen when he said, “I would suggest we think this through. I think the fundamentally different designs suggest that there might be different regulatory approaches.”

Both Massari and Senator Toomey are right: it is critical that government officials take the time to think this through and understand why cryptocurrencies need to be regulated in any form.

To that end, at the third installment of the CMFA’s series, Peter van Valkenburgh recommended the audience heed the lessons of the law of the horse––specifically, Frank Easterbrook’s Cyberspace and the Law of the Horse. Easterbrook argues,

Error in legislation is common, and never more so than when the technology is galloping forward. Let us not struggle to match an imperfect legal system to an evolving world that we understand poorly. Let us instead do what is essential to permit the participants in this evolving world to make their own decisions.

The first step is recognizing when one has become trapped in the trilemma of cryptocurrency regulation. The second step is breaking free of the misguided assumption that regulation is a given and one need only label cryptocurrencies so they can fit into the existing framework. Finally, the third step is addressing the question of why cryptocurrencies need to be regulated at all. Only then will a system emerge that benefits all Americans.