The New York Times yesterday provided an in-depth look at the Biden White House’s plans to “transform the economy” through “dramatic interventions to revive U.S. manufacturing” — heavy on economic nationalism, industrial planning, and manufacturing jobs. If that approach sounds familiar, it should: it’s essentially the same gameplan that Biden’s predecessor used, with the only major difference being Biden’s emphasis on “green” industries like wind turbines, as compared to Trump’s love of steel and other heavy industry.

Both presidents, however, seem to share a soft spot for the automotive industry and U.S. autoworkers. Trump sought to boost automotive jobs through both tariff threats (on dubious “national security” grounds) and restrictive “rules of origin” provisions in his NAFTA replacement, the USMCA. Biden is reportedly looking to boost those same jobs through increased domestic production of electric vehicles and “critical parts like batteries.” According to the Times, Biden’s team was strongly influenced in this regard by a 2018 United Automobile Workers (UAW) report advocating “huge” government “investments” (subsidies) in the U.S. auto industry, and arguing that “advanced vehicle technology should be treated as a strategic sector to be protected and built in the U.S.” Judging from this report and various Biden administration statements to the Times, Biden’s plans appear to be a cut-and-paste job from the Trump era, with a little green tinting.

As I discussed in a new Cato policy analysis, however, economic nationalism — tariffs, subsidies, “Buy American” restrictions, and the like — is a shoddy way to “revive” the U.S. manufacturing sector and in fact often weakens it. Even if you assume we need a large U.S. industrial base, moreover, global and historical data from before the trade wars and pandemic show little need for any “revival” at all: typical measures of “deindustrialization” (jobs and manufacturing’s share of U.S. GDP) say little about the sector’s health, while the things that do matter — output, value-added, foreign direct investment, R&D and capital expenditures, and financial performance — are looking fine, especially in the industries that matter most for national security.

This includes the U.S. automotive industry, which — despite two recessions — enjoyed significant increases in real (inflation-adjusted) value-added and gross output between 1997 and 2018:

A detailed breakdown of the industry’s output over this period also shows a dynamic sector that responds to market forces — for example, U.S. consumers’ growing preference for trucks and SUVs over cars — while total output continued to climb:

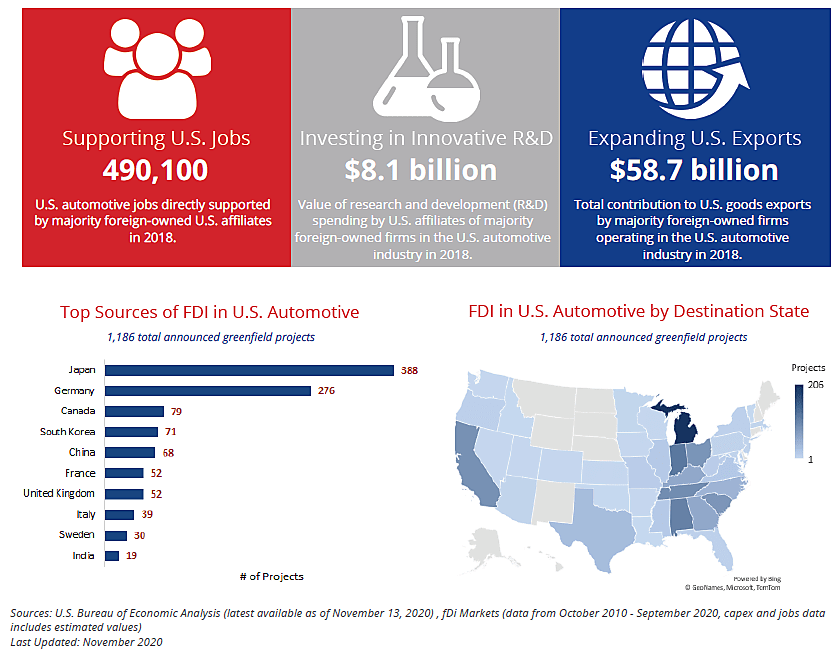

The American automotive sector has also been a top target for foreign direct investment (FDI). According to the U.S. government’s Select USA program–

Since Honda opened its first U.S. plant in 1982, almost every major European, Japanese, and Korean automaker has produced vehicles and invested more than $75 billion in the United States. The U.S. affiliates of majority foreign-owned automotive companies directly support more than 400,000 U.S. jobs. Additionally, many automakers have U.S.-based engine and transmission plants, and conduct R&D, design, and testing in the United States. Total foreign direct investment in the U.S. automotive industry reached $114.6 billion in 2018.

Meanwhile, the industry’s financial performance and capital expenditures have also been healthy:

Industry group the Auto Alliance further estimates that automakers invest around $19 billion per year in research and development (R&D) in the United States, accounting for about one-sixth of global automotive R&D spending. According to recent Wall Street Journal analysis, industry investment is today concentrated in electric vehicles due to heightened consumer demand, and it has attracted a flood of additional private capital — foreign and domestic — to expand the supply chain for batteries and related materials in the United States. In particular, U.S. battery-making capacity is expected to increase more than sixfold by 2030, from 60 to 383 gigawatt hours of annualized production, and investors are lining up to establish U.S. battery materials (anodes, cathodes, and raw materials like lithium) facilities to support that production. Again, consumers are driving (no pun intended) the trend: “[m]oving more battery production to the U.S. will help car companies and their suppliers bring down costs, a step that is important for consumers to adopt electric vehicles more widely.” By contrast, the Journal notes that “[t]here are risks if consumer demand doesn’t materialize as expected. An attempt to expand U.S. battery production—mostly through government funding under then-President Barack Obama —stumbled early last decade when car companies failed to see demand for electric vehicles materialize as anticipated.”

Lessons abound.

Of course, the U.S. automotive industry utilizes imports to remain globally competitive, and automakers have offshored some vehicle production — especially small cars — to Mexico and other countries. However, these same companies also export significant volumes of cars, trucks, and SUVs to the rest of the world: in 2018, for example, “the United States exported 1.8 million new light vehicles and 131,200 medium and heavy trucks (valued at over $60 billion) to more than 200 markets around the world, with additional exports of automotive parts valued at $88.5 billion.”

And it is this very global integration that makes Trump/Biden economic nationalism so counterproductive for the auto industry. As President Trump’s tariffs taught us, protectionism here tends to spark protectionism abroad against imports of American-made goods. This retaliation, combined with higher input costs due to Trump’s tariffs, ended up costing U.S. automotive jobs, which since the Great Recession had been a positive outlier:

Indeed, a 2019 analysis from the New York Federal Reserve found that about one-third of all U.S. manufacturing job growth between 2010 and 2017 in was in the automotive sector — a trend that the chart above shows continued through 2018 when Trump’s trade wars began — and primarily located in America’s “auto alley,” stretching from Michigan to Alabama (inclusive of the Carolinas and Georgia):

Many of these jobs are in non-union, foreign-owned plants in the “right to work” states of Alabama, Georgia, Kentucky, South Carolina, and Tennessee, as well as in more union-friendly states like Ohio. According to the Detroit News in 2019, for example, “the Detroit Three automakers are an island of UAW production surrounded by foreign transplants that now make up 48% of U.S. vehicle production… up from just 17% in 2000. Non-union employment rose from 15% of the industry at the century’s turn to 39% in 2013.” The article adds that average production worker salaries at Honda’s Maryville, Ohio plant are $80,000 per year (plus benefits) — a “pattern of high-paying, non-union employment [that] has been repeated across the country in transplants from Toyota Motor Corp. in Kentucky to BMW AG in South Carolina to Kia in Georgia to Volkswagen AG in Tennessee.” Hourly wages are a little lower than UAW jobs, but flexibility in foreign automakers’ non-union labor contracts — which can, unlike UAW contracts, be benchmarked to local manufacturing norms — has given non-“Big Three” automakers a significant cost advantage that has supercharged their domestic competitiveness and enabled them to gobble up market share. As one economist put it, “[s]ince the bankruptcy, GM has made itself a 21st-century company talking publicly about competitive wages and closing plants to remain profitable. But the UAW and their political supporters are still using rhetoric right out of 1979. It’s not clear that they understand that the game has changed.”

Maybe the old game, not the U.S. automotive sector, is what the Biden administration is really trying to “revive”?