Beginning in 2019, California is set to implement a new law that requires companies fill around 40 percent of corporate board positions with women.[1] This means California is following the lead of european countries including Norway, Belgium, France, Germany, Iceland, Italy, and Spain which have legislated similar reforms for corporate boards.

The California mandate may face federal and state legal challenges. However, assuming the law is implemented, observers will no doubt be interested to see whether it accomplishes its objectives. For example, will the law improve corporate leadership representation for women?

A study published today in The Review of Economic Studies sheds light on possible outcomes of California’s policy. The study reviews the effects of Norway’s 2003 reform which similarly requires companies fill 40 percent of corporate board positions with female directors, or be dissolved. As the study recounts,

“In theory, quotas can be an effective tool to improve gender equality… Because qualified women might be harmed by an absence of networks to help them climb the corporate ladder, quotas can provide the initial step up that women need to break this cycle. If discrimination is the key factor for the under-representation of women, quotas might help overcome business prejudice (and improve efficiency) by forcing more exposure to talented women in positions of power (Beaman et al 2009, Rao 2013).”

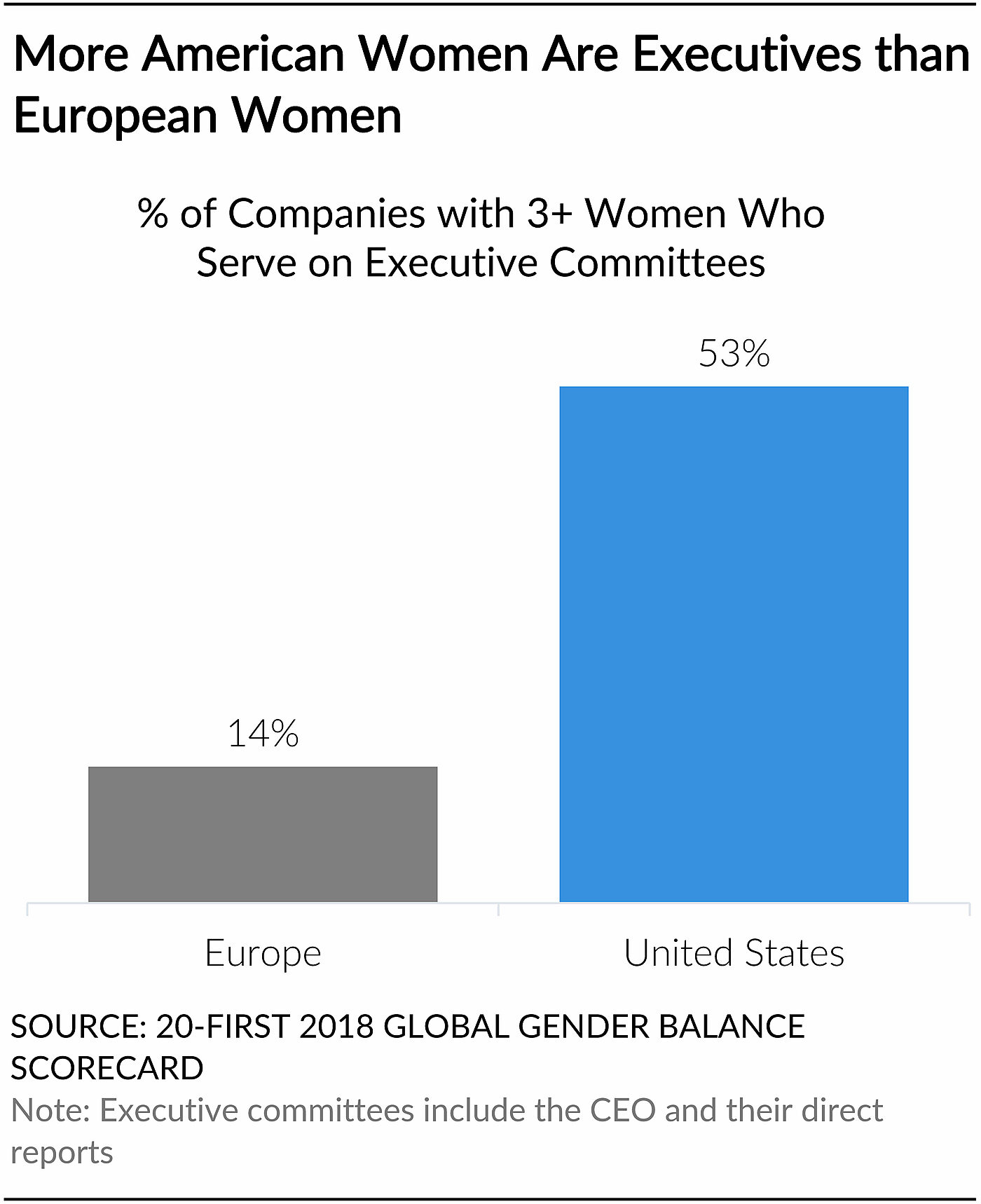

But rather than finding quotas improved corporate leadership representation for women, the study found quotas were helpful for the elite women that were appointed to corporate boards, but not female workers generally. For example, the authors find “no evidence of improvements for women working in firms most affected by the reform,” and board quotas were also not helpful to women who were qualified to be on boards but not selected for them.

Indeed, the authors find that “overall, seven years after the board quota policy fully came into effect, we conclude that it had very little discernible impact on women in business beyond its direct effect on the women who made it into boardrooms.”

In summary, if the law is intended to simply increase nominal women on corporate boards, this is likely to occur. But if California’s quotas are intended to help working women generally, or meaningfully change the trajectory of working women’s careers? If Norway is any indication, they probably won’t.

For more information on the results of corporate board quotas please see the Cato paper, The Nordic Glass Ceiling.

[1] Two female directors are required for boards consisting of 5 directors, and three female directors are required for boards consisting of 7 directors.