The Cato Institute and Heritage Foundation recently co-hosted a debate in which interns from both organizations debated whether conservatism or libertarianism is the better philosophy. At the conclusion of the debate, the Cato Institute conducted a survey of debate attendees finding important similarities and striking differences between millennial conservative and libertarian attendees.

Full LvCDebate Attendee Survey results found here

The survey finds that libertarian and conservative millennial attendees were similar in skepticism of government economic intervention and regulation but were dramatically different in their stances toward immigration, LGBT inclusion, national security, privacy, foreign policy and perceptions of racial bias in the criminal justice system.

While the survey is not a representative sample, this survey offers a snapshot of engaged conservative and libertarian millennial “elites” who have higher levels of education and political information, and who chose to come to this event. To date, little information exists on young conservative and libertarian elites. Since these attendees are politically engaged millennials, their responses may provide some indication of the direction they may take both movements in the future.

Eighty-percent of millennial respondents self-identified as either conservative (41%) or libertarian (39%): This post will focus on these conservative and libertarian millennial attendees.

Economics Bind Conservative and Libertarian Millennial Attendees

Libertarian and conservative millennial attendees were clearly similar on questions related to government intervention in the economy. Both libertarians and conservatives overwhelmingly endorsed the idea that the free market can better solve problems than government (98% and 95% respectively), that government regulation of business too often does more harm than good (100% and 93%), and that people who work hard can get ahead (85% and 97%). Furthermore, 96–98% of both groups preferred a “smaller government” that offered fewer services and low taxes over a “larger government” that offered more services with high taxes.

While national polls find that about 6 in 10 Americans favor raising taxes on households making over $250,000 a year (including 30% of Republicans) fully 9 in 10 libertarian and conservative millennial attendees opposed such an action.

Both groups also solidly favor free trade, although a portion of conservatives were less enthusiastic about global competition. For instance, majorities of both groups agreed the country should “eliminate all barriers to trade,” but 100% of libertarians agree compared to 66% of conservatives.

Besides economic policies, however, these young attendees revealed important differences on most of the other important policy issues.

Foreign Policy Divides

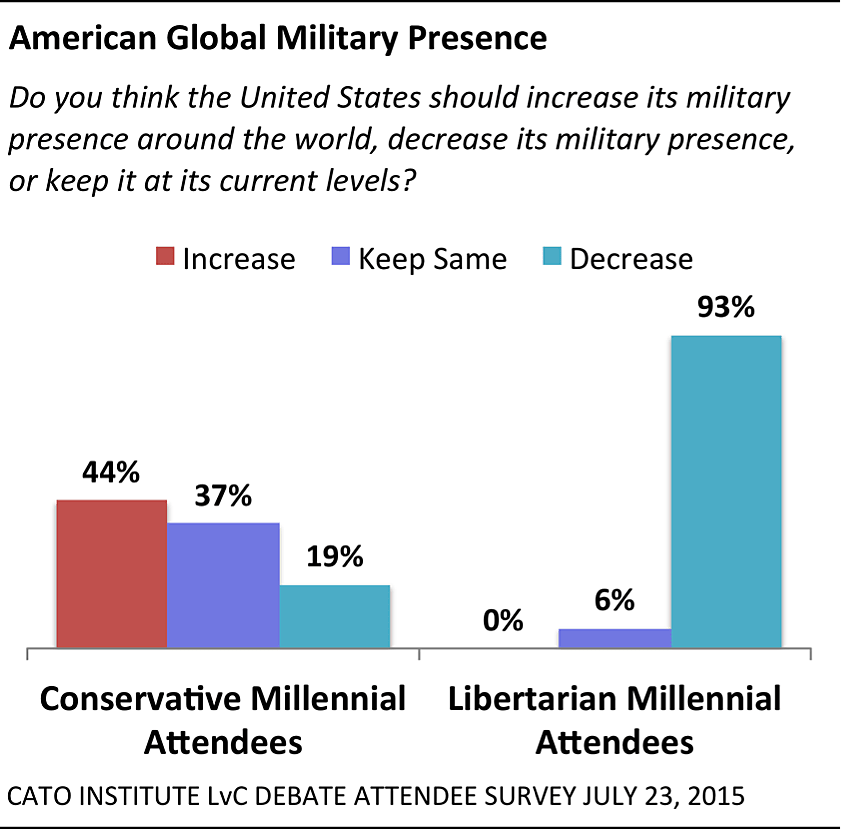

While both libertarian and conservative millennial attendees favored smaller government, they split on cutting defense spending. Fully 96% of libertarians supported cutting defense spending compared with only 32% of conservative millennial attendees.

This disagreement over defense spending maps onto disparate visions about what role the U.S. military should have in the world. While 93% of libertarian millennials wanted to decrease U.S. military presence around the world, only 19% of conservatives agreed. Instead, 44% of conservative attendees thought the United States ought to increase its global military presence and 37% would keep it at present levels.

Similarly, 85% of conservative millennial elites favored sending ground troops to participate in a campaign against ISIS while 74% of libertarian millennial elites opposed this action. However, these positions were not rock solid. Fifty-one percent of conservatives said they “somewhat” supported sending ground troops and 37% of libertarians “somewhat” opposed doing so.

National Security: Is Edward Snowden a Hero or Traitor?

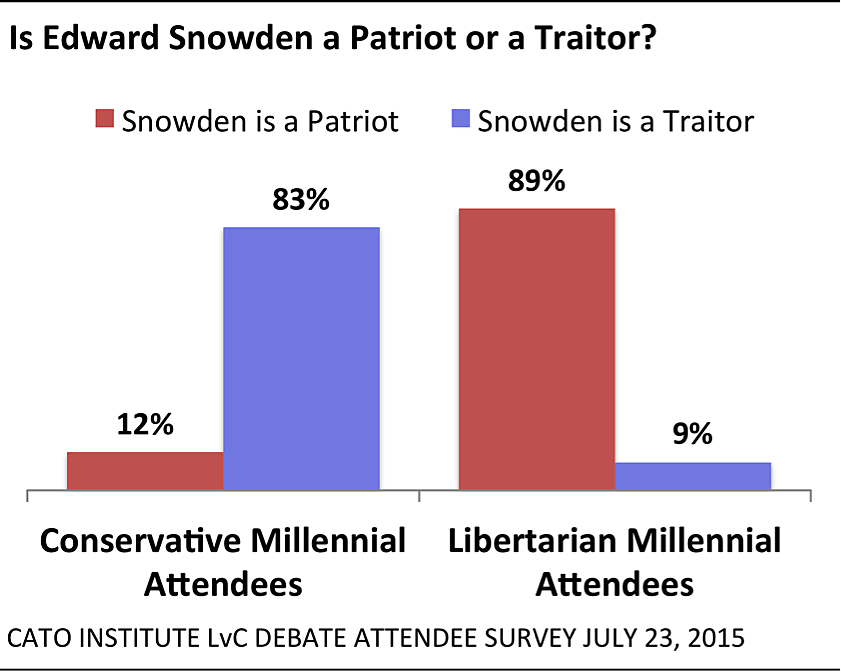

Both conservative and libertarian attendees tended to disapprove of government’s “collection of telephone and internet data as part of anti-terrorism efforts.” But libertarian millennials opposed much more fervently (96%) than did their conservative peers (51%). Forty-five percent of these young conservative elites favored domestic surveillance to fight terrorism compared to 2% of libertarians.

Despite shared opposition to government domestic surveillance, both groups were diametrically opposed in their evaluation of Edward Snowden, the former government contractor who leaked classified information about these programs to the media. Fully 9 in 10 libertarians said Snowden is a “patriot” while 8 in 10 conservatives said he is a “traitor.”

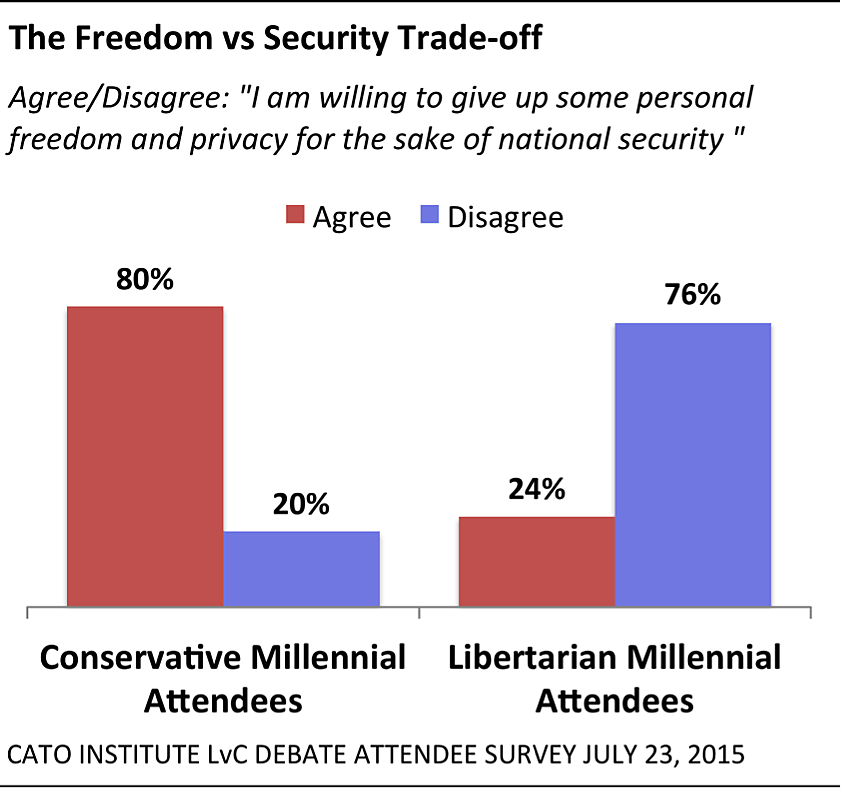

Conservative and libertarian attendees made the trade-off between freedom and security differently, explaining some of these results. While 80% of conservative millennials would “give up some personal freedom and privacy for the sake of national security” 76% of libertarian attendees would not.

Accord on Criminal Justice Reform; Division Over Perceived Systemic Racial Bias

Both conservative and libertarian millennial elites tended to support criminal justice reforms. However, libertarian millennial attendees tended to be more sympathetic to charges of racial bias in the criminal justice system.

Majorities of both groups favored eliminating mandatory minimum prison sentences for people convicted of possessing or selling drugs. However, libertarians were more in favor (87%) than conservatives (54%). In fact fully 76% of libertarians “strongly favor” eliminating this mandatory minimum compared to 22% of conservative attendees.

Majorities of both groups also agreed that local police departments using “drones, military weapons, and armored vehicles is not necessary for law enforcement purposes” but rather is going too far. Yet libertarians were far more likely than conservatives to oppose police militarization (96% to 56%).

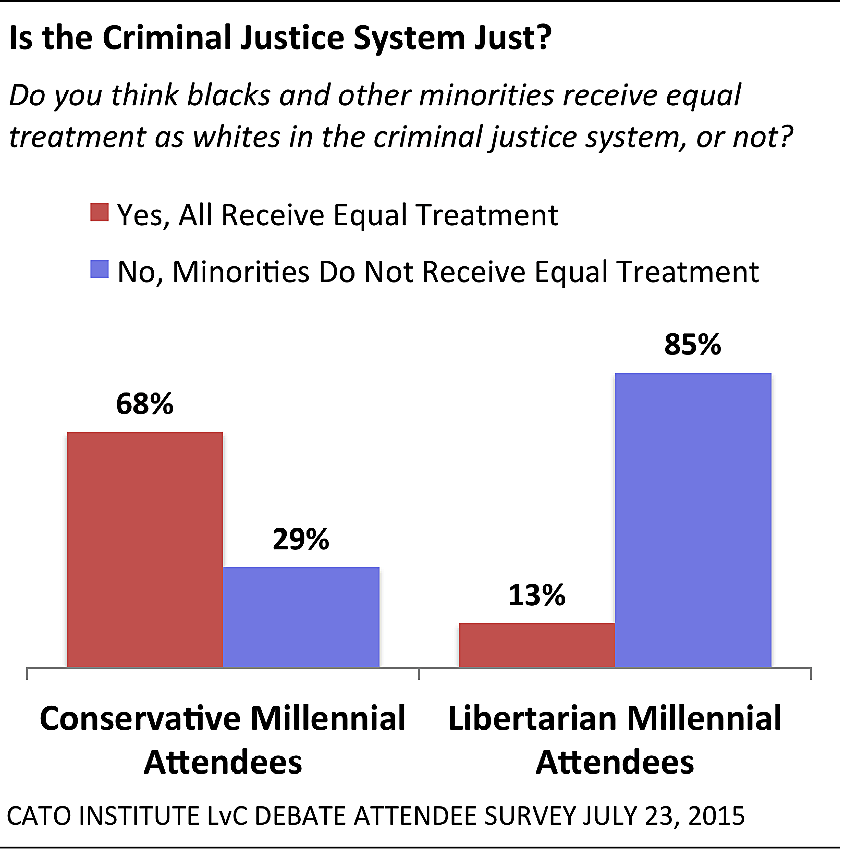

Striking differences emerged between libertarian and conservative attendees in the perception of racial bias in the criminal justice system. Sixty-eight percent of conservatives thought minorities receive equal treatment under the law. In contrast, 85% of libertarians felt that African-Americans and other minorities do not receive equal treatment as white Americans in the criminal justice system.

Similarly 85% of libertarians felt that police in “most communities” are “more likely to use deadly force against a black person.” However conservative attendees disagreed and 64% said that “race doesn’t’ affect police use of deadly force.”

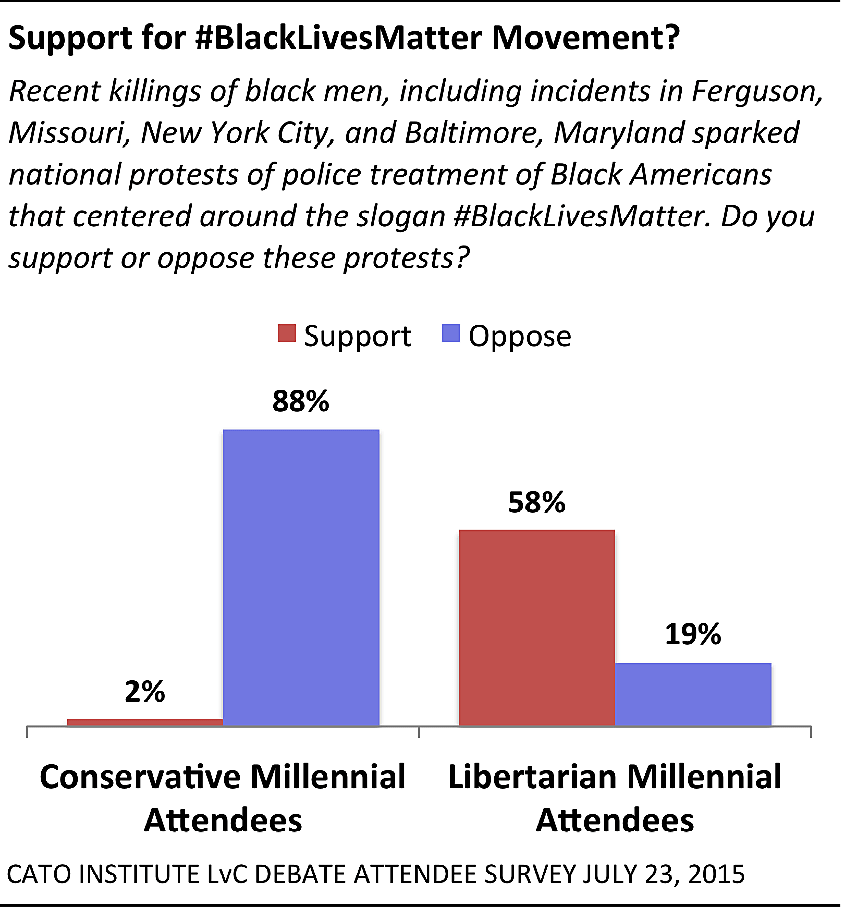

Since the conservative attendees did not perceive significant racial bias in the law enforcement, it’s not surprising that 88% said they opposed the “national protests of police treatment of Black Americans that centered around the slogan #BlackLivesMatter,” including 59% who strongly opposed.

In contrast, 58% of libertarian millennials support the #BlackLivesMatter protests; the remainder said they didn’t know enough to say (25%) or they opposed (19%).

Both Open to Easing Immigration Process, Split Over Unauthorized Immigration

Both libertarian (93%) and conservative (66%) millennial attendees supported making it “easier for people to immigrate to the United States,” although libertarians were significantly more supportive.

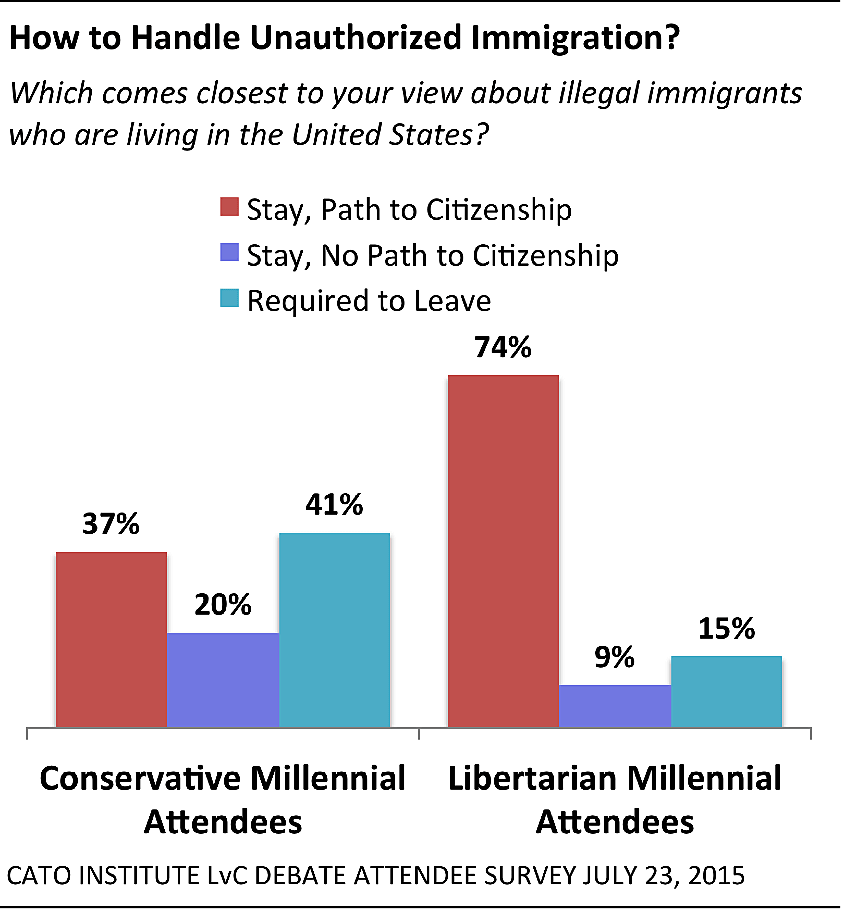

However, major differences emerged between conservative and libertarian elite attendees on what to do about illegal immigration. A majority (61%) of conservatives opposed a pathway to citizenship for people in the United States illegally, including 41% who wanted these individuals to leave the United States. In contrast, 74% of libertarian millennials favored a pathway to citizenship for unauthorized immigrants and only 15% said they should leave.

Additionally, 69% of conservative elite attendees supported the United States “constructing a large wall along the border with Mexico.” In stark contrast, 91% of libertarian attendees opposed building a border wall including 65% who strongly opposed doing so.

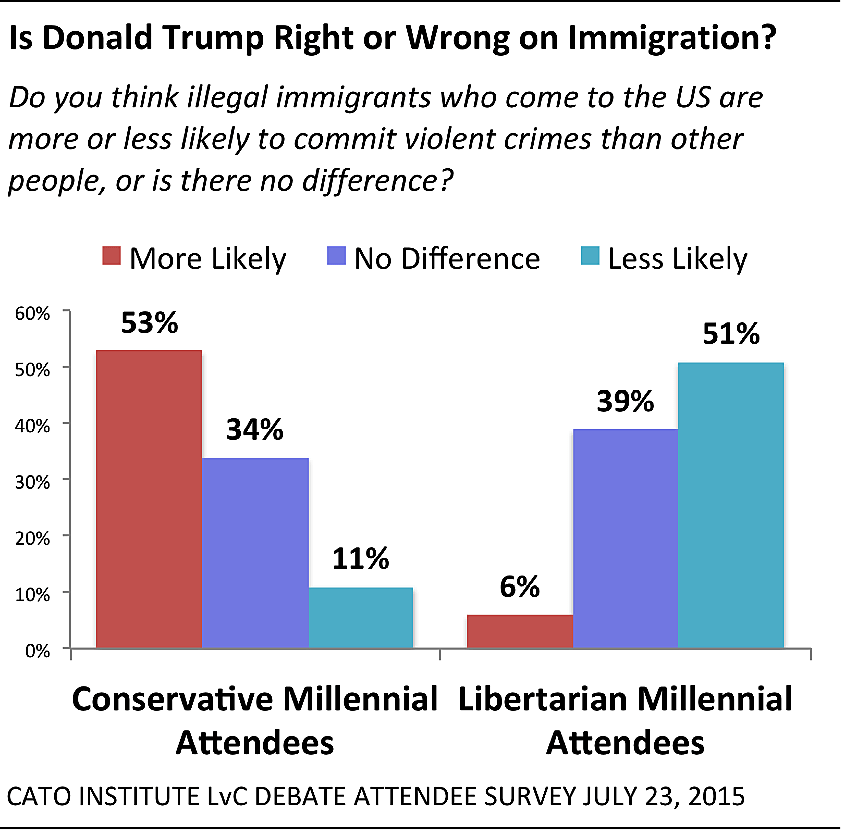

Libertarian and conservative attendees also differed in their perception of unauthorized immigrants’ propensity to commit crimes in the United States. A slim majority (53%) of conservative attendees thought unauthorized immigrants are “more likely” to commit crimes while conversely 51% of libertarians thought they are “less likely” to do so.

In sum, both libertarian and conservative millennial attendees were friendly toward legal immigrants, but only libertarians were also friendly to undocumented immigrants.

LGBT and Abortion Issues Divide

In June the Supreme Court effectively legalized same-sex marriage in the United States; however, conservative and libertarian millennial attendees disagreed about this outcome.

Fifty-nine percent of conservative attendees thought same-sex marriage ought to be illegal, while 85% of libertarian attendees thought it should be legal.

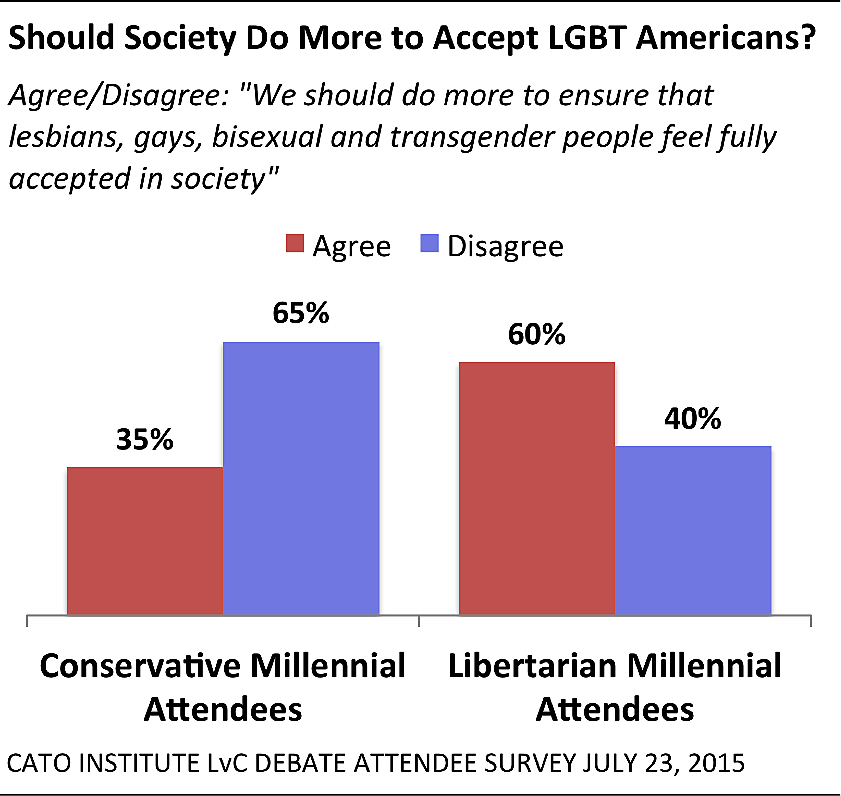

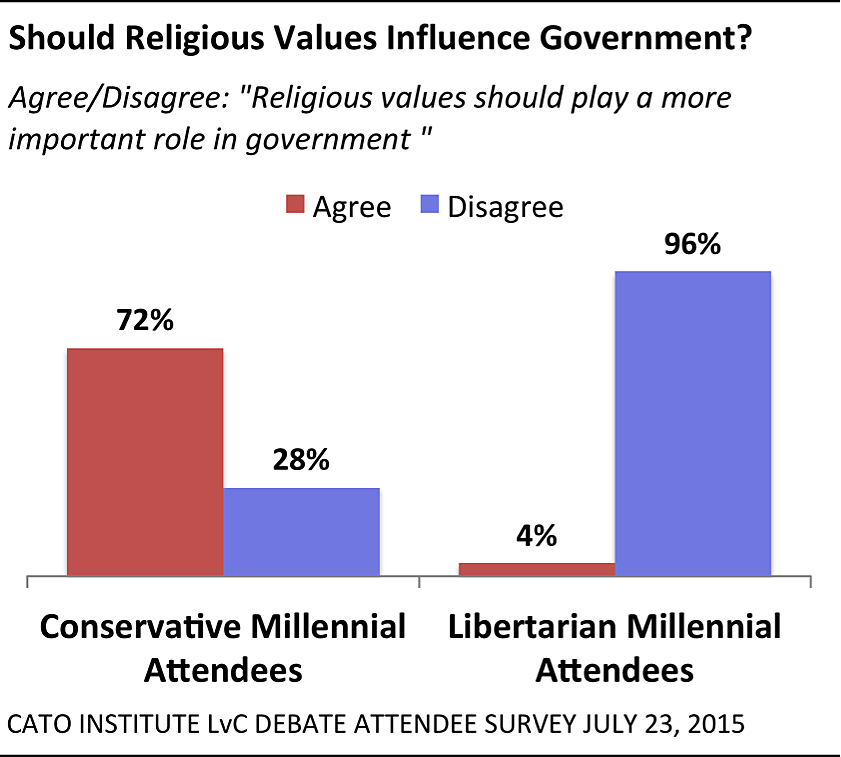

However, this difference isn’t just about legal definitions of marriage. Sixty-percent of libertarian attendees felt that “we should do more to ensure that lesbians, gays, bisexual and transgender people feel fully accepted in society,” while a nearly equal share of conservatives disagreed.

This disagreement maps onto larger differences in worldview. Ninety-six percent of libertarians agreed that “we should be more tolerant of people who choose to live according to their own moral standards” compared with 54% of conservatives.

Part of these differences might be explained by the fact that 72% of conservative attendees agreed that “religious values should play a more important role in government” while 96% of libertarian attendees disagreed.

Conservatives were more religious than libertarian attendees. A slim majority (51%) of conservative elites said they attend religious services once a week or more compared to 19% of libertarians. Instead, 31% of libertarians said they never attend.

When it comes to abortion, conservatives were fervently pro-life (93%), but libertarian attendees were divided. A slim majority of libertarians (51%) said they were pro-choice, but a sizable minority (41%) also said they were pro-life.

Free Speech and Autonomy Tends To Unify

Both conservative (76%) and libertarian (98%) millennial attendees were more supportive than Americans nationally (43%) in allowing a Muslim clergyman to “preach hatred against the United States” in a public speech.

Furthermore, conservative and libertarian attendees tended to oppose outright bans on a number of personal activities including gambling, online pornography, and using marijuana. However, the groups differed significantly in how much the government should regulate these activities. In addition, cocaine divided the attendees: 76% of conservatives wanted it banned and 93% of libertarians wanted it legalized.

What Are the Priority Issues?

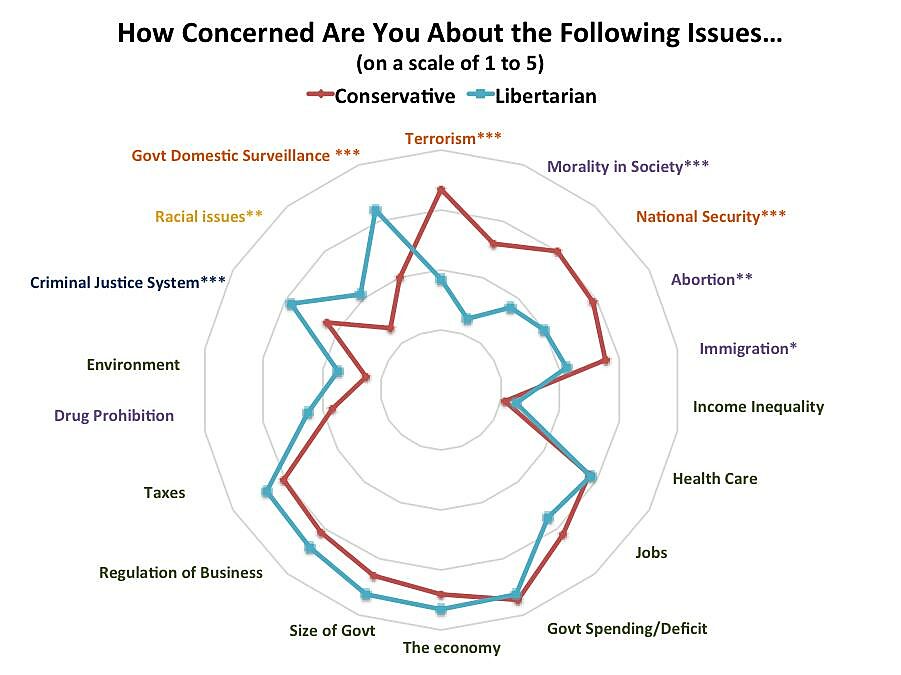

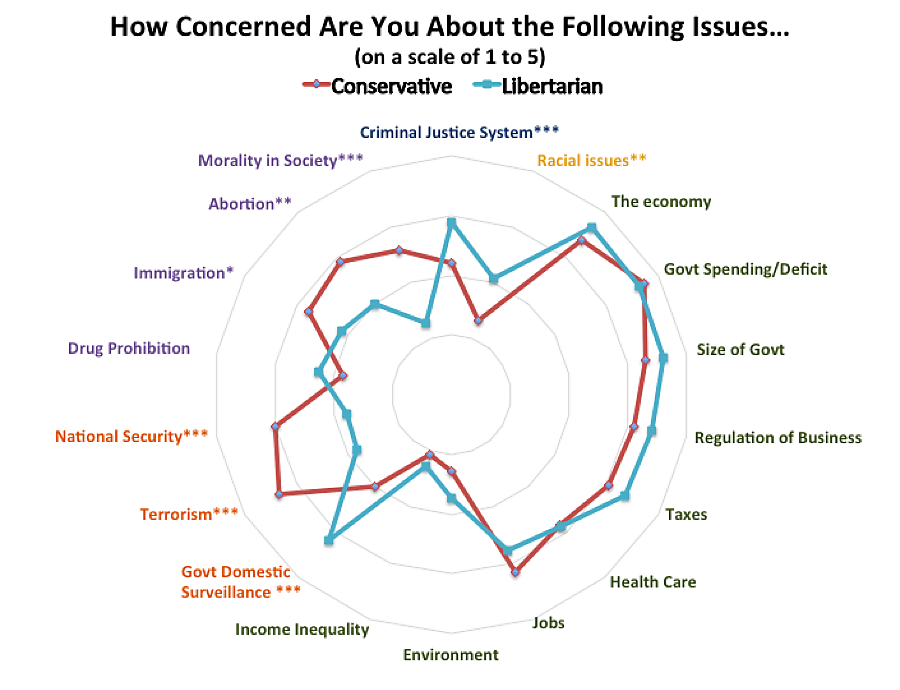

The survey asked respondents to rate on a scale of 1 to 5 how concerned they were on eighteen different issues, including on economics, spending, national security, immigration, drugs, criminal justice, morality, racial issues, income inequality, the environment, etc.

The top five issues for conservatives attendees were: 1) Government spending/deficit 2) The economy 3) Terrorism 4) Size of Government 5) Jobs. The top five issues for the libertarian attendees were 1) The economy 2) Government spending/deficit 3) Size of Government 4) Regulation of Business 5) Taxes.

Statistical tests were run to determine if conservative and libertarians elites rated these issues significantly different. The following chart shows that the two groups were statistically significantly different on all the national security, criminal justice, social/cultural, and racial issues, except for drug prohibition. Both libertarians and conservatives were equally concerned about all the economic issues.

Note: This chart displays the mean level of concern across 18 different issues for both conservative and libertarian millennials who attended the Libertarianism v. Conservatism intern debate at the Cato Institute. Moving from the inner to the outer circles indicates an increasing level of concern for each respective issue. Results from statistical tests are shown which indicate if conservatives and libertarians significantly differed in their concern for the issue ** p < .01 * p < .05. Green: Economic/Govt Size related issues, Blue: Criminal Justice, Yellow: Racial Issues, Orange: National Security issues, Purple: Social and Cultural related issues.How Do They Identify Politically?

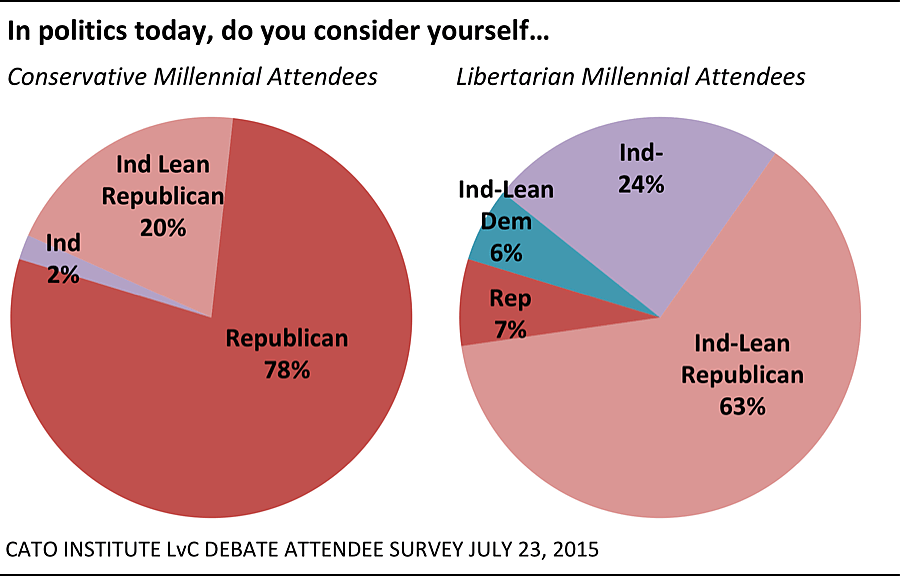

At first glance, conservative millennial attendees appeared much more Republican than the libertarian millennial attendees, but once independents were probed, both conservatives (98%) and libertarians (70%) revealed they were part of the Republican coalition. Nevertheless, a quarter of libertarian millennial attendees said they were completely independent of either party.

Since these attendees are politically engaged and tend to lean Republican, their agreements and conflicts may portend future debates the GOP may have to confront in the future.

If these results have any external validity for party insiders in the future, the GOP will find itself largely in agreement around limiting government intervention in the economy. However, the GOP will have to contend with significant disagreements over the future of American foreign policy, balancing freedom and national security, the influence of religion on politics, its approach toward immigration and immigrants—legal or not, whether it will make concerted efforts to include LGBT people and understand the experiences of minorities in the country.

Who Won the Debate Depends on Whom You Ask

Who won the debate depends on whom you ask:

- Among libertarian millennial attendees, 96% said the libertarian team won and 4% said the conservative team won.

- Among conservative millennial attendees, 67% said the conservative team won and 33% said the libertarian team won.

- If you combine the libertarian and conservative attendees 64% said the libertarian team won and 36% said the conservative team won.

- Among the remaining moderate, liberal, and progressive attendees, 8 in 10 said the libertarian team won and 2 in 10 said the conservative team won.

In sum, the 2015 intern libertarianism vs. conservatism debate goes to the libertarian team.

Full LvCDebate Attendee Survey results found here

Methodology

The Cato Institute conducted a survey of attendees at the debate hosted by the Cato Institute and Heritage Foundation in which interns at both organizations debated whether conservatism or libertarianism is a better political philosophy on July 23, 2015.

An email was sent to every person who pre-registered or walked-in to the debate at the conclusion of the event with a link to a Qualtrics survey. Emails were sent to 588 people, of these we estimated 360 were in attendance at the debate. In total, we collected 179 surveys from debate attendees, producing a response rate of 30% among all those emailed and 50% of estimated attendees. The margin of error for this attendee survey is +/- 5.2%. Of the 179 surveys, millennial attendees completed 139, including 59 self-identified millennial conservatives and 54 self-identified millennial libertarians. The margin of error for millennial conservatives is +/- 8.9% and for millennial libertarians is +/- 9.6%. The remaining survey respondents included self-identified moderates, liberals, progressives, and some over the age of 35 and thus not considered a millennial attendee.