The Merchant Marine Act of 1920, commonly known as the Jones Act, is impossible to defend with a straight face. The Act requires that all people and goods travelling from one U.S. port to another be carried on U.S. owned, flagged and crewed ships. The rationale usually offered these days in support of the Act is that it protects American jobs, and that our military needs to have a fleet of ships it can borrow in case of some sort of emergency. Neither can be taken seriously. For starters, the Jones Act probably costs us jobs. The high shipping costs engendered by the Jones Act encourage businesses to ship more things via rail or truck. Where that’s not possible (as with Puerto Rico), it incentivizes businesses to import goods, rather than buy from a domestic customer and pay the prohibitively expensive toll the Jones Act imposes. In either case, fewer jobs result. The Act makes it cheaper for U.S. livestock farmers to buy grain from overseas than from American sources, and forces states such as Maryland and Virginia to import their road salt rather than buy it from Ohio. The East Coast of the U.S. cannot afford to get lumber from the Pacific Northwest. And shipping oil from Texas to New England costs about three times as much as shipping it to Europe. The Jones Act survives because it’s hard for people to see what it costs them. As long as constituents aren’t complaining, politicians are happy with the status quo — especially since ship builders will write big checks to anyone willing to protect the Act. The recent relaxation of the Jones Act for Puerto Rico has the potential (albeit slight) to change this calculus, but since it is scheduled to only last for ten days, the residents of this island won’t see how much they could potentially save from not having this burden. And those savings would be immense: In a study I recently did with Russ Kashian, we estimated that U.S. consumers would save billions of dollars if we got rid of the Jones Act. And places like Puerto Rico, Hawaii and Alaska would benefit most of all, since they are overly dependent upon shipping prices. However, as those are only two low population states and a territory with no voting representation, their inconveniences won’t resonate much with Congress.

Cato at Liberty

Cato at Liberty

Topics

Government and Politics

In Regulation: The Jones Act’s Bloody Cost

After some sorely needed scrutiny, the Trump administration has just announced that it will temporarily suspend an ugly piece of corporate welfare in order to speed aid to hurricane-stricken Puerto Rico.

The Merchant Marine Act of 1920, better known as the Jones Act, requires that all people and goods transported by water between U.S. ports be transported on U.S.-built ships, with U.S. owners, registered and sailing under the U.S. flag, and crewed by U.S. citizens or permanent residents. The law originally was justified as ensuring a robust U.S. merchant marine in wartime, but it really is (and probably always has been) a cynical sop to American shipbuilders, shipping companies, and (ostensibly) their employees because it gives them market power that allows them to charge higher prices.

Policy analysts have long understood this; for instance, a 1991 Regulation article by Federal Maritime Commission member Rob Quartel chastised the law for creating “America’s Welfare Queen Fleet.”

Traditionally, Jones Act criticism has focused on its financial harm to American consumers. One recent estimate is the law results in higher prices totaling $1.9 billion a year, which is about $5.50 for each American man, woman, or child. But now there’s growing evidence that it also exacts a cost in human lives.

In the new issue of Regulation, North Carolina State University economist Thomas Grennes argues that because American-built vessels are significantly more expensive than comparable ships built elsewhere, American shipping companies operating under the Jones Act delay replacing their vessels. As a result, American-flagged vessels are nearly three times older on average than comparable foreign vessels. International data show that as ships age, they become more dangerous for their crew. Indeed, the 2015 sinking of the El Faro, a Jones Act vessel, raised troubling questions about the law’s role in the deaths of the ship’s 33-member crew.

Now, the Gulf hurricanes have shown another potentially deadly aspect of the Jones Act.

As President Trump recently noted, “you can’t just drive” truckloads of supplies and workers to Puerto Rico; they must be transported by plane and boat. Hence the Jones Act has long bedeviled the island; one estimate is that the prices of goods shipped from the U.S. mainland to Puerto Rico are twice as high as they would be without the law. But following Hurricane Maria, the law has transformed from a costly nuisance into a potentially deadly one; desperately needed relief has been dramatically slowed and made more expensive by the law’s artificial barrier on what ships can move supplies from the U.S. mainland to the stricken island—and what ships do carry those supplies must be diverted from other transport work between U.S. ports.

The White House previously temporarily suspended the Jones Act for emergency supplies heading to the hurricane-ravaged Gulf states, using a provision in the law that is intended for national defense purposes. Now that suspension has been extended to Puerto Rico.

But instead of temporarily suspending the law under a dubious “defense” claim, Congress and the White House could go further and repeal it. After all, pointless corporate welfare isn’t only a bad thing during emergencies. For a rough draft of repeal legislation, lawmakers could use Sen. John McCain’s unsuccessful 2015 bill.

Given congressional leaders’ oft-made statements of concern for American consumers and given the Trump White House’s vows to pare back unjustified regulations and “drain the swamp,” repeal of this harmful piece of corporate welfare should be a slam dunk. Unless, of course, lawmakers have different priorities than helping consumers, protecting sailors, and aiding people like those who desperately need aid in Puerto Rico and the Gulf states.

When Statutes Conflict, Agencies Shouldn’t Get to Pick Which One They Like More

One federal statute says that Rony Estuardo Perez-Guzman, who claims refugee status, isn’t eligible for asylum. Another one says that he is. Whose duty is it to reconcile this glaring legislative contradiction, and how should it be remedied?

Mr. Perez-Guzman fled to the United States to escape violence and persecution in Guatemala. He was stopped by border patrol agents and deported, but reentered the United States because he still feared for his life. The asylum statute (8 U.S.C. § 1158) guarantees the right of “any alien … physically present in the United States … irrespective of such alien’s status” to apply for asylum. The reinstatement statute (8 U.S.C. § 1231) states that an individual who has previously been removed from the United States “may not apply for any relief under this chapter” (which includes asylum). The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit held that the two statutes conflict—so far so good—and are therefore are ambiguous, which is where the judicial mischief starts. A finding of statutory ambiguity often leads courts to simply defer to administrative agency interpreting the statute, which here means the Justice Department refused to let Perez-Guzman apply for asylum.

Perez-Guzman has petitioned the Supreme Court to review his case. Cato has filed an amicus brief supporting that petition and challenging the lower-court holding that statutory conflict triggers Chevron deference (named after the 1984 Supreme Court case that created the doctrine).

Chevron deference provides that courts must defer to administrative agency interpretations of the authority granted to them by Congress (1) where the intent of Congress is intentionally ambiguous and (2) where the interpretation is reasonable or permissible. The Court has curtailed Chevron by carving out important limitations, which mean that Chevron deference will not apply without an implicit congressional delegation for an agency to “fill in the gaps” in ambiguous statutory language.

The notion that Congress intentionally drafts ambiguous language so an agency may interpret that language as it sees fit is itself suspect as a matter of the separation of powers: our Constitution doesn’t allow a delegation of legislative power to the executive. But the notion that Congress commits that same folly by drafting directly conflicting statutory language is ludicrous.

The Administrative Procedure Act mandates that courts interpret statutory provisions and determine the applicability of agency actions; it attempts to reinforce the importance of the separation of powers. Chevron asks us to forget all about it. Expanding the doctrine further, to incorporate not just ambiguous statutes but conflicting ones will further erode the rule of law.

If the Court wants a way to resolve these conflicting statutes, it should look to the “rule of lenity.” It provides that in construing ambiguous criminal statutes, courts should resolve the ambiguity in favor of the defendant. The rule is also applied in deportation statutes. It reflects the fundamental principle that Congress must speak clearly if it wants to impose on an individual an especially severe deprivation of liberty—which deportation most assuredly is. When removal from the country is at stake, courts shouldn’t defer to an agency interpretation that commands a greater infringement on liberty than a statute requires (however restrictive or expansive that statute may be).

The Supreme Court should review Perez-Guzman v. Sessions, restore the balance of constitutional power, and reclaim the judiciary’s authority to say what the law is.

D.C. Just Can’t Walk Away from Burdening Business

A week ago Walter Olson noted, quoting the Washington Post, that

D.C. lawmakers are preparing to take a break from further beefing up labor standards [in] an abrupt shift for a city whose leaders have been in the vanguard of the national campaign for workers’ rights.…

“Businesses like certainty, and if we’re constantly changing the tax burden or the tax environments, or constantly changing the regulatory burden, then it becomes more difficult to do business in the District,” said D.C. Council Chairman Phil Mendelson (D), who has proposed a moratorium through the end of 2018 on bills that would negatively affect businesses.

Meanwhile, at the very moment that councilmembers are promising to stop adding new burdens to businesses and job creation, the Council is debating a new rule that would require employers who offer their workers free parking to offer that same benefit—in cash—to workers who want to walk, bike, or ride public transit to work instead.

“This bill would be easy to implement,” says one bike commuter, “because it builds on DC’s Commuter Benefits Law, which requires all employers with 20 or more employees to provide them with the option to use their own pre-tax money to pay for transit.” Easy for the regulators, anyway. Maybe even easy for business HR departments, since “the systems employers already have to make” for other mandated benefits can be adjusted. But each new mandate requires some new learning for HR officers, some effort to notify employees, some adjustment to the payroll software. Those burdens add up.

Not to worry, though! Businesses might even save money under this proposed new mandate:

Proponents point out that the bill could even wind up benefiting employers in the long run. According to the World Resource Institute, converting a non-active employee into a bike commuter saves $3,000 in employer health care costs and reduced absenteeism.

Critics insist that corporations are greedy, crafty, always focused on the bottom line. And yet they believe that there are all these free lunches—these $20 bills lying on the sidewalk waiting to be picked up, as economists say—that businesses are just missing. Just maybe, when businesses oppose new regulations, they have a better sense of their costs and opportunities than councilmembers and activists do.

D.C. currently has an unemployment rate of 5.9 percent, higher than the national average of 4.4 and much higher than the D.C. metropolitan area rate of 3.9 percent. If the Council would like to see some of those suburban jobs move into the District, it might consider reducing the burdens on business.

Related Tags

Poll: 61% Oppose Firing NFL Players Who Refuse to Stand for National Anthem, but 65% of Republicans Say Players Should be Fired

Today we’re releasing one question from the forthcoming national Cato 2017 Free Speech and Tolerance Survey of 2,300 Americans conducted by the Cato Institute in collaboration with YouGov.

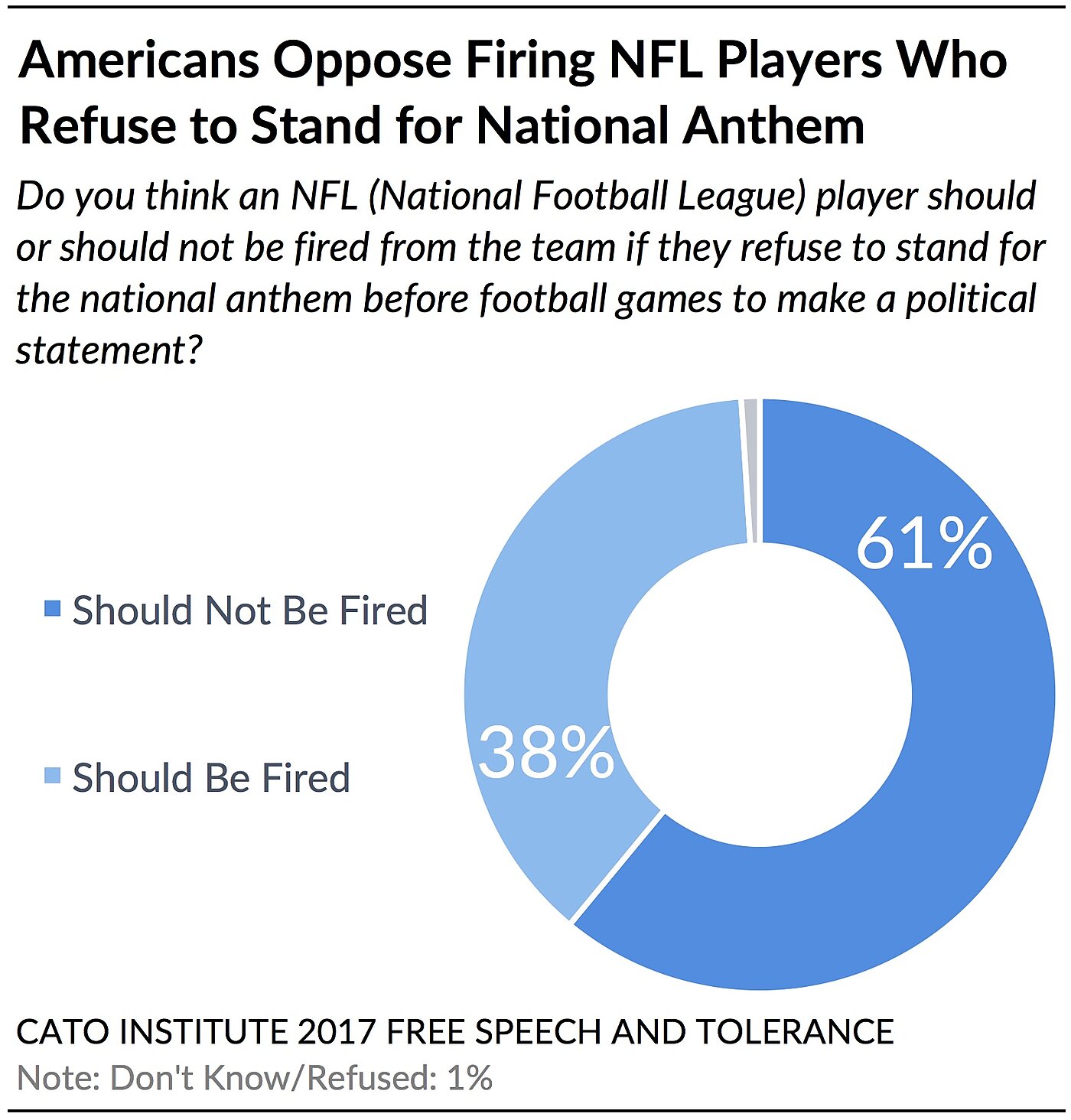

The national survey finds that a solid majority, 61%, of Americans oppose firing NFL (National Football League) players who refuse to stand for the national anthem before football games in order to make a political statement. These results stand in contrast to President Trump’s remarks over the weekend and his urging NFL teams to fire players who refuse to stand for the anthem. A little more than a third (38%) of Americans align with Trump and support firing these players.

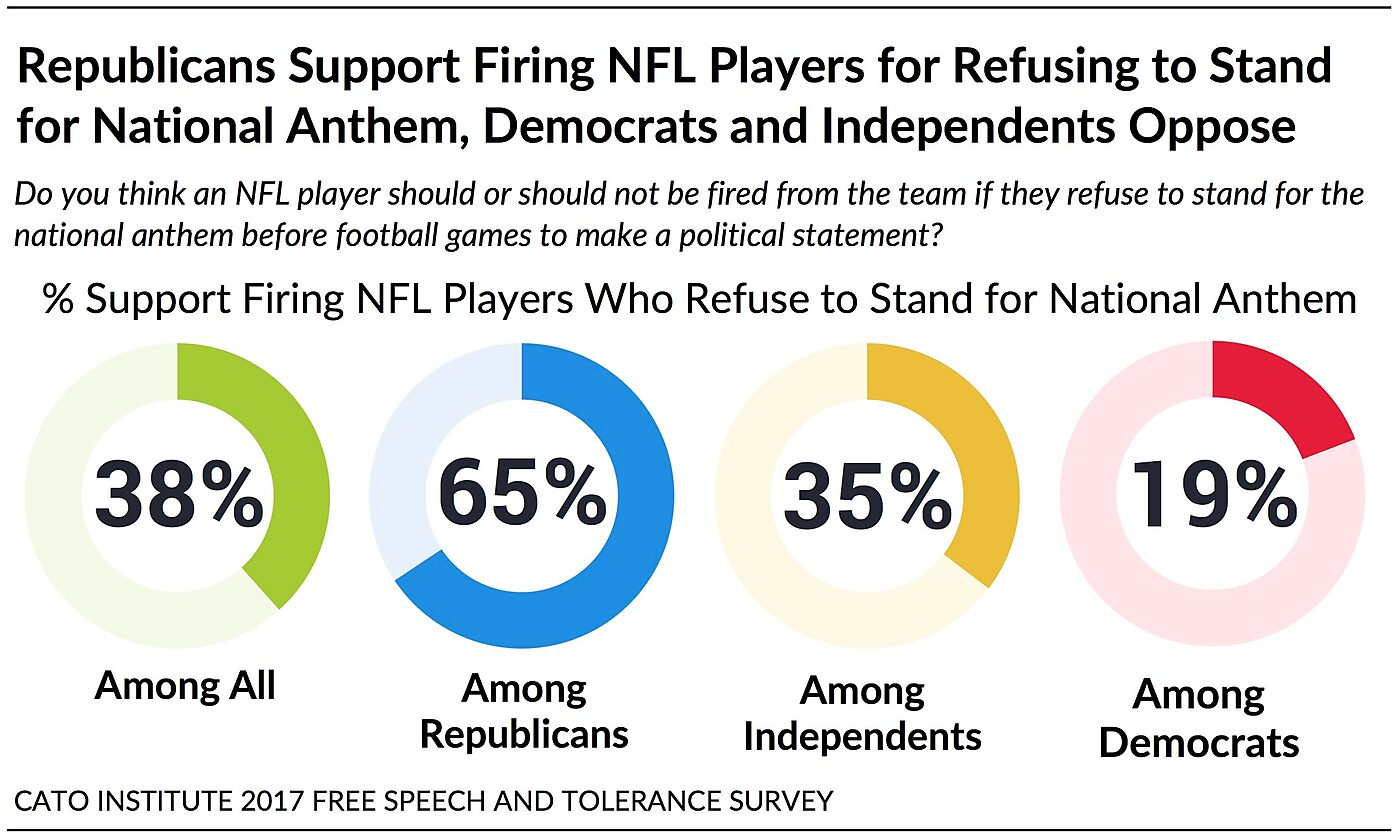

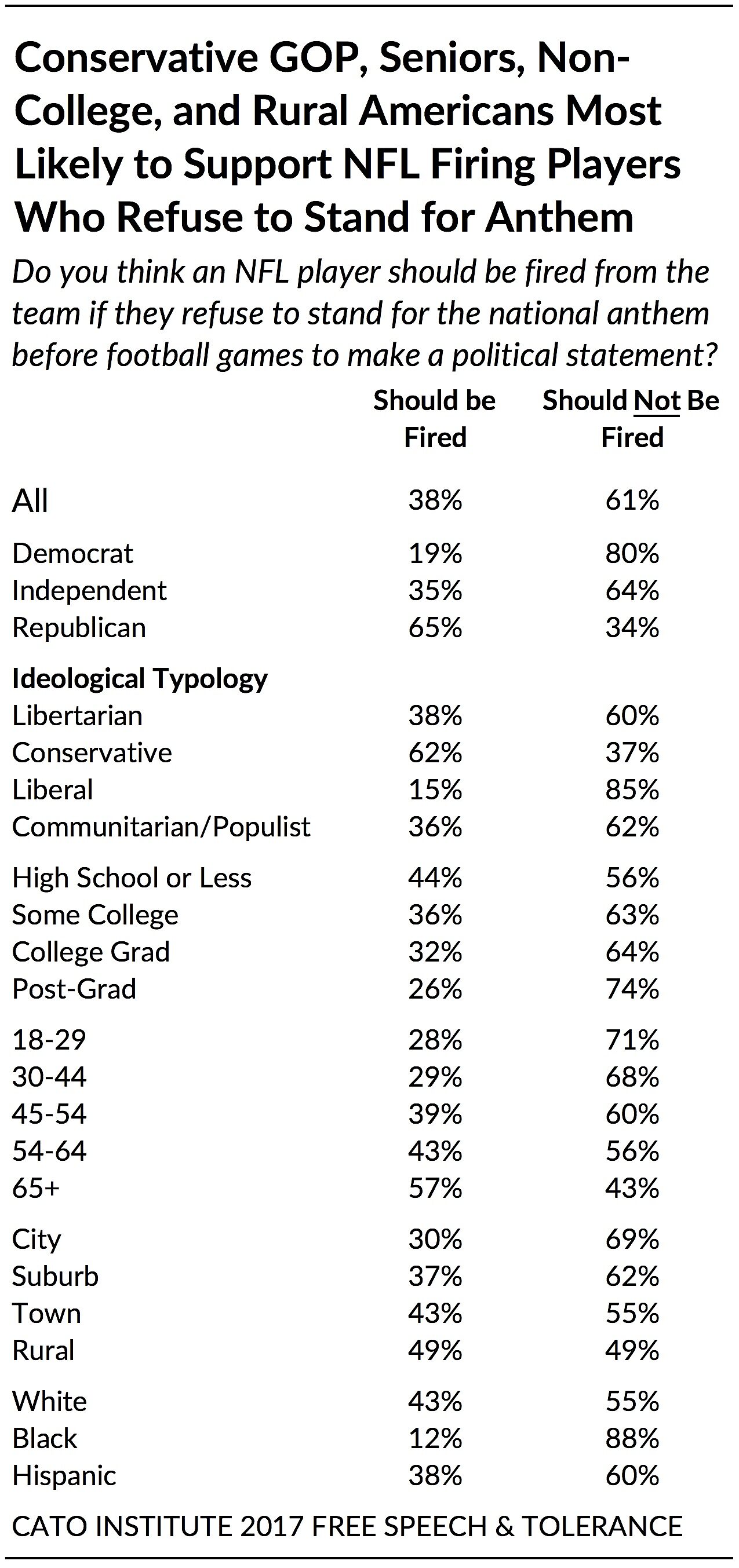

Conservative Republicans stand out in their support for firing NFL players who refuse to stand for the national anthem. Nearly two-thirds (65%) of Republicans say NFL players should be fired for this reason. Only 19% of Democrats and 35% of independents agree. Punishing NFL players for their political speech distinguishes political Conservatives from Libertarians. Using a political typology method to identify these ideological groups, the survey finds that Conservatives (62%) are the only political group to support firing NFL players. Conversely, 60% of Libertarians, 85% of Liberals, and 62% of Communitarians (social conservatives who support larger government) all oppose punishing players.

People who are older, with less education, and living in smaller towns and rural communities are most likely to support punishing NFL players who kneel during the national anthem in political protest.

A majority (57%) of Americans over 65 think such players should be fired while 71% of Americans under 30 think they should not. Those without college degrees (44%) are more likely than college graduates (32%) and those with post-graduate degrees (26%) to similarly support punishing NFL players who engage in this form of political protest. Americans living in rural communities are divided in half over whether teams should fire NFL players who refuse to stand for the national anthem. Conversely, those living in large urban centers solidly oppose (69%) such firings.

Majorities across racial groups oppose firing NFL players who kneel during the national anthem before football games. However, African Americans (88%) are about 30 points more likely than Hispanics (60%) and whites (55%) to oppose.

Not wanting to fire NFL players because of their political speech doesn’t mean that most Americans agree with the content of this speech. Surveys have long shown, as well as this one, that most oppose burning, desecrating, or disrespecting the American flag. Thus, Americans appear to make a distinction between allowing a person to express (even controversial) political opinions and endorsing the content of their speech. The public can be tolerant of players’ refusing to stand for the national anthem, even while many disagree with what the players are doing.

In sum, Americans don’t want to strip people of their livelihoods and ruin their careers over refusing to stand for the national anthem. Even if they don’t agree with the content of the speech, that doesn’t mean they support punishing people who do.

Topline results and methodology can be found here.

The Cato Institute 2017 Free Speech and Tolerance Survey was designed and conducted by the Cato Institute in collaboration with YouGov. YouGov collected responses online August 15–23, 2017 from a national sample of 2,300 Americans 18 years of age and older. The margin of error for the survey is +/- 3.00 percentage points at the 95% level of confidence. The full survey report is forthcoming.

Federal Pay Tops Most Industries

Federal worker compensation is rising faster than compensation in the private sector. On average, federal workers now earn 80 percent more in wages and benefits than other Americans, as examined in this blog yesterday. The data come from the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), and is discussed further in this study.

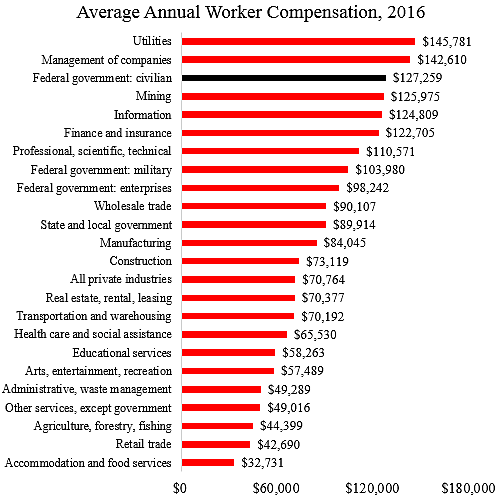

The BEA breaks down the data by industry. The chart below shows average compensation for the BEA’s 19 major private industries and the military, state and local governments, federal civilian workers, and federal government enterprises (mainly the postal service).

The federal government has the third highest paid workers in the United States after utilities and the management of companies. Federal compensation is higher, on average, than compensation in the information, finance and insurance, and professional and scientific industries.

Federal compensation is twice as high as compensation in the education industry, and is almost three times higher than compensation in retail trade.

Further discussion of federal pay is here.

Related Tags

Federal Pay Outpaces Private Pay in 2016

The Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) has released data on worker compensation for 2016. The data show that wages and benefits for federal-government workers grew faster than for private-sector workers last year. Federal workers now receive 80 percent more compensation, on average, than do workers in the U.S. private sector. I am including federal civilian workers here, not those in the uniformed military.

Average wages for federal workers increased 2.0 percent in 2016, which outpaced the average private increase of 1.3 percent. Federal workers had average wages of $88,809 in 2016, or 49 percent more than the average wages of private workers of $59,458.

However, the federal advantage in overall compensation (wages + benefits) is even larger because of gold-plated federal benefits, such as pension benefits. Total compensation for federal workers increased 2.5 percent last year, on average, more than double the 1.2 percent increase for private workers.

As a consequence, average federal compensation in 2016 was $127,259, which was 80 percent higher than average private compensation of $70,764. The federal advantage of 80 percent is up from just 50 percent in 2000.

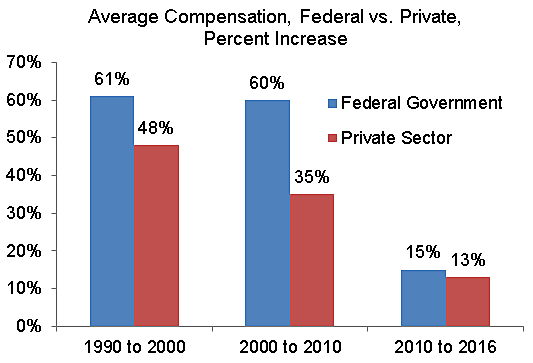

The figure below shows that federal compensation grew much faster than private compensation during the 1990s and 2000s. Federal increases slowed during a brief wage freeze under President Obama, but have accelerated again in recent years. Since 2010, federal compensation increases have edged out private increases as a result of the strong growth in federal benefits.

This study examines the latest data and discusses federal compensation issues in more detail.