As the global semiconductor shortage persists, chipmakers have renewed their efforts to convince Congress to hand them tens of billions of taxpayer dollars. Earlier this year, the U.S. Senate passed a $52 billion subsidy package for this very purpose. Its fate remains unclear in the House of Representatives, but a vote on some sort of government support for domestic chip production is expected in the coming weeks (though perhaps after the new year). Before members vote again on any such subsidies, however, we provide below seven reasons why broad, strings-free subsidization of U.S. semiconductor manufacturing – similar to what passed the Senate – is not only costly and unnecessary, but perhaps even harmful for the industry itself:

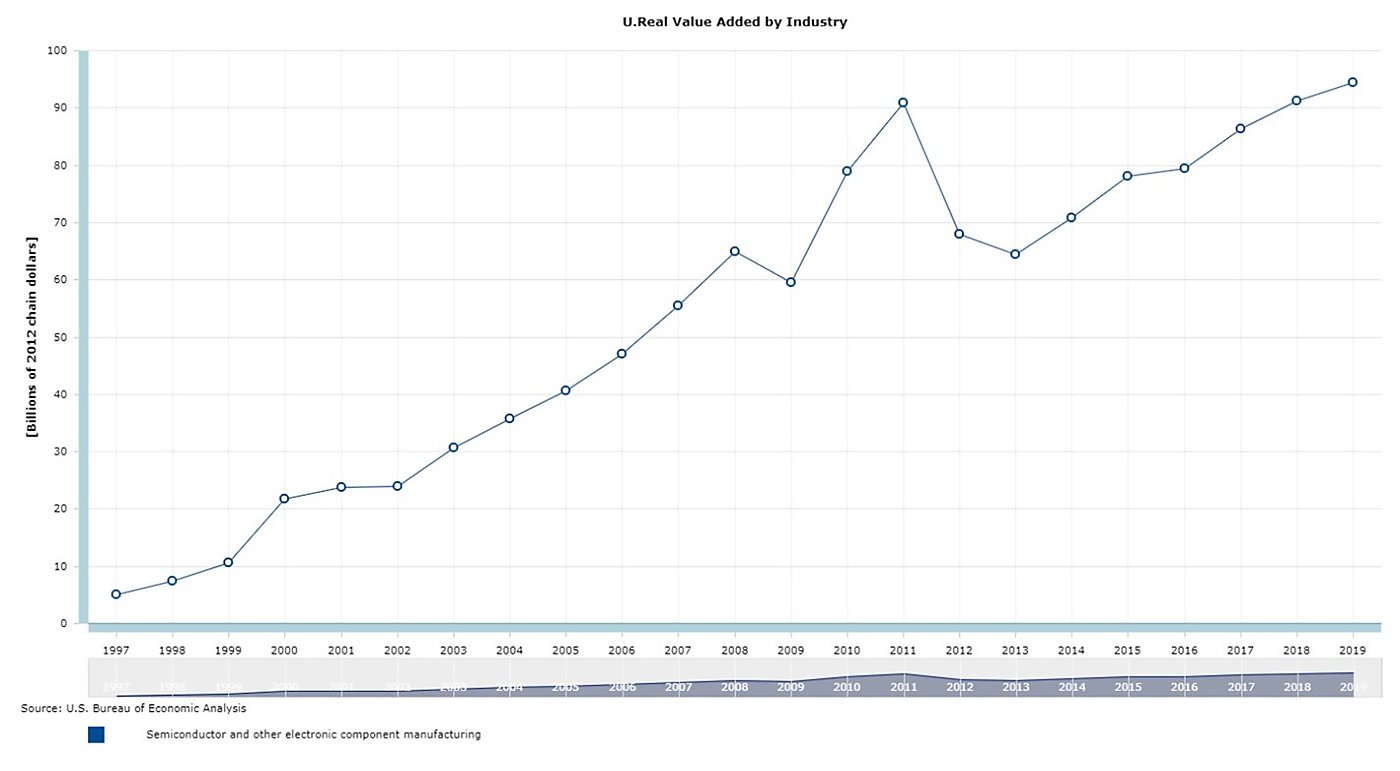

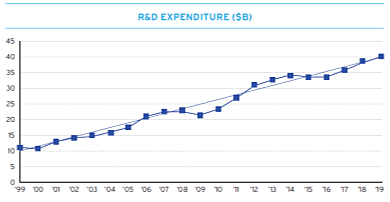

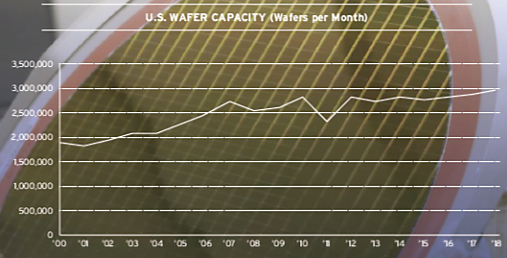

1. American chip manufacturing has been increasing, and the industry is healthy. While America’s share of global chip production has fallen from 37% in 1990 to 12% in 2019 – a stat subsidy advocates mention at every opportunity – real output and capital expenditures (CapEx) in the United States have increased substantially over the same period (see Figures 1 and 2). This growth, moreover, is not merely in dollar terms. As a 2020 report from the Semiconductor Industry Association shows, domestic wafer manufacturing capacity has increased from under 2 million units per month in 2000 to nearly 3 million units in 2018 (see Figure 3), and U.S.-based semiconductor firms still produce a plurality (44%) of their wafer supply domestically – far more than in any other country.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

2. Semiconductor manufacturers are already investing here and don’t need taxpayer help. There’s arguably never been a better time to be a chip manufacturer, as intense global demand for their products has translated into billions of dollars in revenue and profits. For example, leading chip manufacturer TSMC earned record profits this year, recording roughly $5 billion in profit each quarter. American national champion Intel, meanwhile, is also highly profitable and had almost $21 billion in free cash flow in 2020 – a 23.62% increase from the previous year. Instead of just sitting on this cash, chipmakers are investing around the world, including in the United States. For example, Samsung began operating a Texas manufacturing plant in 2016, is investing in a second Texas facility, and Intel and TSMC have each opened new facilities in Arizona. According to Harvard’s Willy Shih, these U.S. plans will proceed with or without federal subsidies because chipmakers want “to take advantage of the country’s skilled workforce and to be close to specialized US equipment manufacturers that churn out many of the tools needed to make cutting-edge semiconductors.” (He also acknowledges that the companies’ subsidy demands are really just a cash-grab.) On the R&D side, IBM recently revealed the world’s first 2 nanometer chips at its upstate New York facilities, and U.S. “fabless” semiconductor innovation remains world-beating. Overall, Stevens Institute of Technology professor George Calhoun estimates that private investment in American chip manufacturing will total roughly $80 billion through 2024. These are simply not companies that need taxpayer subsidies – a fact even Intel’s own CEO has confirmed.

3. Giant multinational corporations can handle their own geopolitical risk assessment and mitigation. Subsidy supporters often justify their position by pointing to the geopolitical risks that firms incur when buying semiconductors made in China or in neighboring Taiwan. However, it beggars belief that large multinational corporations haven’t already made such calculations when determining their sourcing decisions: geopolitical risk is always a major factor that companies consider when making overseas investment and supply chain decisions, and large investment firms such as BlackRock even operate “Geopolitical Risk” dashboards for their clients. Furthermore, large chip-consuming companies such as Ford and Apple are already moving to adjust their semiconductor supply chains – for example by partnering with manufacturers for new, “nearshored” supply. Indeed, the Washington Post just recently reported that U.S.-based GlobalFoundries’ customers “are ready to invest to expand production to secure steady supplies” in the United States. Thus, if large multinational chip consumers deem Taiwan to be too risky and want chip supplies elsewhere, there’s an easy fix: they can pay for it. And that’s just what they’re doing.

Finally, similar geopolitical considerations exist on the supply side: Samsung has been expanding operations in the U.S. for supposed geopolitical reasons, and Intel has opened facilities in both the U.S. and other countries such as Malaysia, as uncertainty grows over both China and Taiwan. Even Taiwanese firm TSMC has opted to open a U.S.-based plant in Arizona, likely with the intention of growing stateside operations and becoming a part of the Defense Department’s “trusted supply chain.”

4. Subsidies won’t help alleviate the current chip shortage, and probably won’t help with the next one either. Experts like Shih predict that the current semiconductor shortage will ease by the middle or end of 2022, well before any potential subsidies have been disbursed. Moreover, the construction and activation of new manufacturing facilities is a long process; new Intel plants in Arizona, for example, are unlikely to see production start before 2024. Even Biden Administration officials acknowledge that subsidies won’t help address the current crisis, with Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo noting in November that the goal of the bill is to help stave off future crises. However, subsidies for today’s technologies might not help solve tomorrow’s problems either. For example, while onshoring leading-edge 3‑nanometer chips is a core objective of U.S. subsidy proponents, Calhoun predicts that this “process node” approach will eventually be replaced by new technologies such as quantum and neuromorphic computing. It’ll be these technologies, not today’s, that’ll be needed down the road.

5. Broad subsidies like these won’t solve narrow (potential) market failures. Even many libertarians generally opposed to government intervention in private industries might concede that such intervention could be needed to solve a real market failure (e.g., a lack of “moonshot” R&D) or clear national security concern (e.g., a lack of chips for laser-guided missiles). However, most of the subsidies now under consideration target neither “bleeding edge” chips nor national security-related ones. Instead, the funds for new U.S. manufacturing facilities have mainly hortatory guidelines, meaning U.S. administering agencies could disregard them and – just like past U.S. subsidy programs – subsidize undeserving companies that just-so-happen to have lobbied the hardest therefor. Indeed, the Senate bill expressly earmarks billions of dollars for older (“mature” or “legacy”) chips because Detroit automakers use them and Michigan Senators helped write the bill.

On the national security front, the subsidies’ lack of focus has exasperated the U.S. companies that actually build the specialized semiconductors used by the U.S. Defense Department, and U.S. law already allows DoD to subsidize critical defense-related manufacturing. Maybe a narrow package targeting bleeding edge R&D and core DoD priorities could be useful, but that’s definitely not what’s being considered.

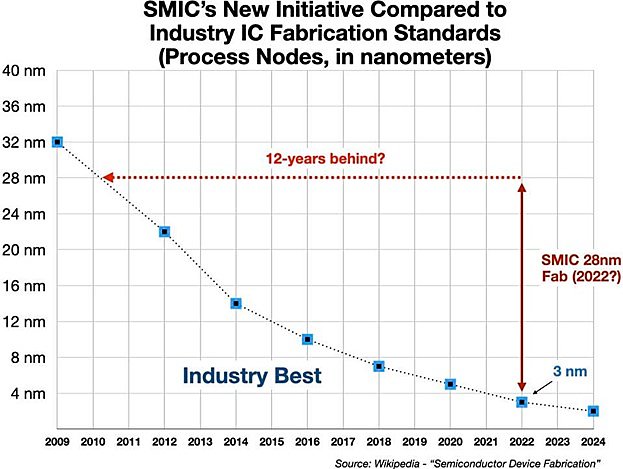

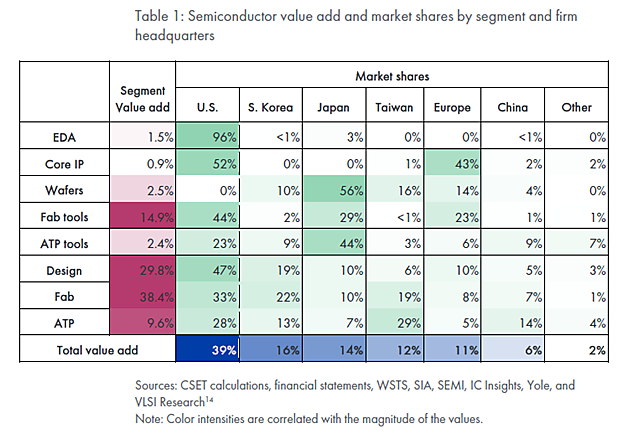

6. China’s rise in the semiconductor world is exaggerated. Just as America’s semiconductor decline has been exaggerated, so too has China’s rise. According to the SIA, for example, the Chinese industry remains years behind its Asian competitors. Calhoun estimates, moreover, that China may be more than a decade behind leading-edge Western chipmakers, as its most advanced companies produce only 28-nanometer chips (see Figure 4). In fact, Calhoun notes that China imports 90% of their semiconductor needs, despite the government spending decades and billions of dollars to achieve national chips greatness. Moreover, of the seven stages of semiconductor production Calhoun identifies, the West has a near-monopoly in or strong domination of six areas. And while China houses a plurality of low-tech foundry facilities, 78% of them are actually located outside China (60% outside of either China or Taiwan). A 2021 report from Georgetown University on the entire semiconductor supply chain corroborates these findings, concluding that “[t]he United States and its allies are global semiconductor supply chain leaders, while China lags” (see Figure 5).

Figure 4

Figure 5

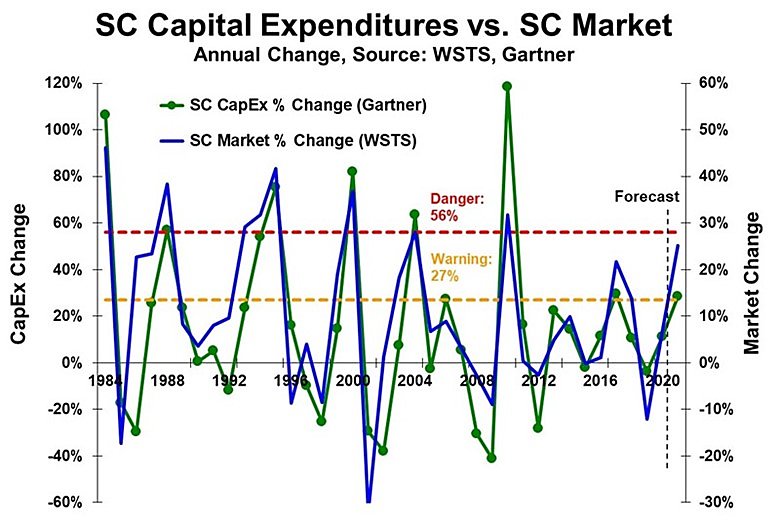

7. Subsidies could cause a semiconductor glut and create trade conflicts. Finally, there is an increasing risk that U.S. subsidies could lead to overcapacity and eventual trade conflicts – especially since other large economies, such as the EU, Korea, and China, are also offering them. As explained in one recent analysis, semiconductor manufacturing is notoriously cyclical with “a long history of strong CapEx leading to over-capacity followed by price collapses and a declining semiconductor market.” Current (i.e., pre-subsidy) industry investment, moreover, is already at levels that typically lead to overcapacity and industry troubles in the following year or two (see Figure 6). As Harvard’s Shih put it, “[u]sually, when everybody rushes to expand capacity, the next scene is not very pretty.” Meanwhile, some investors and industry insiders believe that previous semiconductor demand forecasts were too optimistic, and many large consumers have been “hoarding vast stockpiles” due to current market uncertainty. Thus, many analysts are now concerned that 2023 could see a semiconductor glut, and predictions abound that eventual market oversupply will lead to idle production lines and financial hardship for various chip companies.

U.S. government subsidies would only exacerbate these unstable market dynamics, making potential problems in the industry more likely. They’d also set the stage for international trade conflicts, as nations resort to anti-dumping or anti-subsidy (“countervailing duty”) actions – and eventual duties on subject imports – to protect their struggling domestic semiconductor industries. Similar disputes occurred in the 1980s and 1990s, as the United States imposed various restrictions on memory chips from Japan (and later South Korea) – restrictions that, as we’ve discussed previously, significantly harmed American technology companies and consumers.

Figure 6

In sum, there are no strong economic or national security justifications for throwing tens of billions of taxpayer dollars at domestic semiconductor manufacturing. The U.S. industry is healthy and innovative; major players are swimming in cash, already investing here, and will do so without new subsidies; the “China threat” for semiconductors is – economically and geopolitically – overblown; and subsidies might produce a glut and eventual trade conflicts. Of course, self-interested chipmakers will continue to pretend that their situation is dire, and that only taxpayer cash can save them and the country.

But Congress shouldn’t play along.