The U.S. Border Patrol could soon lose its novel authority to expel border crossers back into Mexico under Title 42 of the U.S. code, a 19th century public health law never previously used to remove people from the United States. Since March 2020, the agency has used Title 42 to ignore the normal process to which crossers are entitled under Title 8 of the U.S. immigration code and force them back into Mexico often within a few minutes of their arrests. The government is also flying some migrants directly back to their home countries under the rule.

Figure 1 shows the number of border arrests by processing type: Title 8 and Title 42. As it shows, the Title 42-era has seen a major increase in the number of total arrests. However, since April 2022, most illegal border crossers have not been subject to Title 42 expulsions. In October 2022—the most recent month available—only 37 percent of crossers were processed under Title 42 rather than Title 8. The number of arrests under Title 8 exceed the peak of arrests under Title 8 during the Trump administration.

In October 2022, 92 percent of expulsions were being used against “single adults,” adults traveling without children, and 91 percent over those expulsions are of single adults from Mexico and the Northern Triangle of Central America (Mexico, Honduras, and El Salvador). Families (adults with children) from these four countries account for another 6 percent of Title 42 expulsions and then all other families account for 2 percent of Title 42 expulsions.

With between a 91 and 96-percent expulsion rate, single adults from Mexico and the Northern Triangle of Central America are the most likely to be expelled of any group that Border Patrol arrests. Family units from the Northern Triangle and Mexico are the next most common with, as of October 2022, a 65-percent expulsion rate. Other single adults are expelled just 8 percent of the time and other groups (families and unaccompanied children) are expelled just 3 percent of the time. In other words, Title 42 is largely directed at single adults and families from the Northern Triangle and Mexico. Other groups are rarely targeted under Title 42.

Title 42 is a policy largely targeting single adults from Mexico and the Northern Triangle, but the number of single adults from these four countries has quadrupled alongside the increased use of Title 42—from an average of about 21,000 per month to nearly 80,000 per month in 2021 and 2022. Much of this increase preceded the rise in other arrests in 2020.

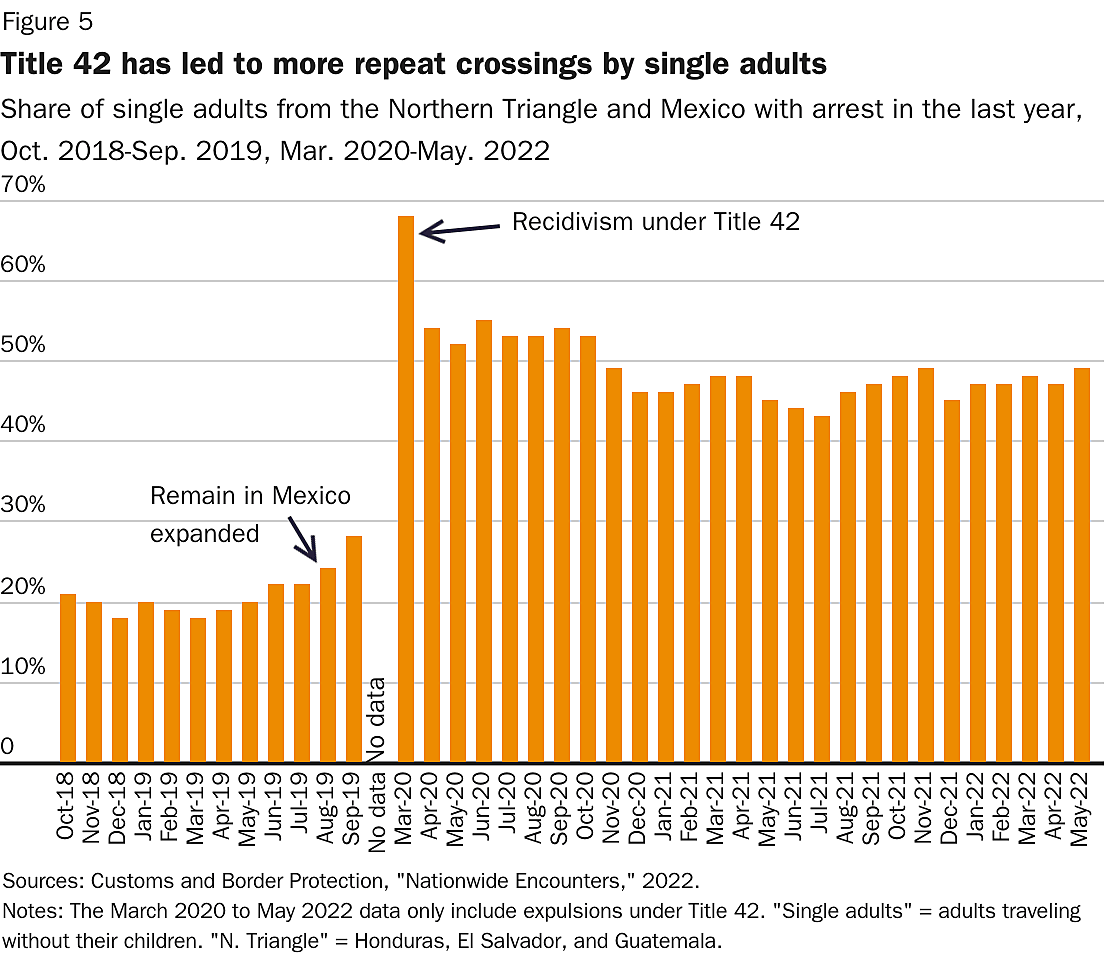

Title 42 does not deter single adults from Mexico and the Northern Triangle from crossing the border. Further evidence is that Title 42 has led to significant increase in recidivism—that is, the share of immigrants who were previously arrested the same year. The recidivism rate surged from about 20 percent in 2019 to 49 percent in 2022—meaning nearly half of single adults arrested under Title 42 from Mexico and the Northern Triangle were previously arrested under this policy. The remain in Mexico policy—which also involved sending people back to Mexico—also led to an increase in recidivism prior to the Title 42 policy.

The primary reason that Title 42 is not a good deterrent for this population is that they are not likely to be seeking to apply for asylum but rather to enter the country without being arrested, so that they can find jobs. Previously, single adults were likely to be incarcerated for an extended period after their arrest and possibly prosecuted criminally and sent to a U.S. prison. “They are sending back people very quickly, in hours,” said one Mexican seeking to cross. “The rumor is that chances of crossing undetected are higher, as you can try and try again without much consequences.”

As a result of the increasing number of attempts, the number of detected successful illegal entries (known as “gotaways”) increased dramatically during the Title 42-era to a level not seen since before the Great Recession. Under Title 42, the number of known gotaways—that is, detected crossers who were not arrested—grew from an average of about 12,500 per month in 2019 to an average of more than 50,000 in 2022.

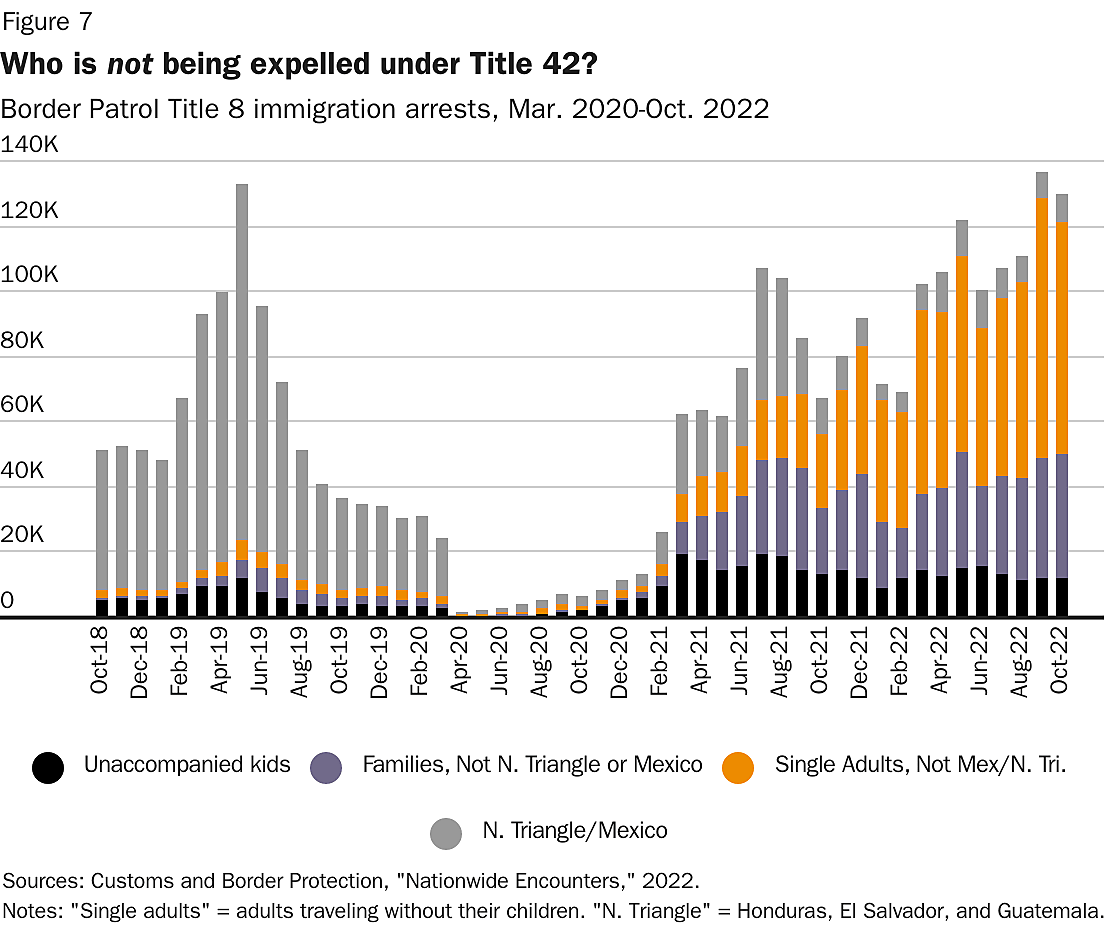

As Figure 7 shows, the demographics of those being processed under Title 8 (the immigration laws) have changed dramatically from 2019 to 2022. In 2019, 85 percent of those processed under Title 8 were families and single adults from the Northern Triangle or Mexico. In October 2022, just 7 percent were those groups. Now 93 percent are from other countries or unaccompanied children. Unaccompanied children (minors traveling without their parents) cannot be expelled to Mexico because the Centers Disease Control specifically excluded them from that order in January 2021.

Immigrants from countries other than the Northern Triangle and Mexico are difficult to expel because they must be flown to their home countries. This is happening to some extent. The government averages about 120 removal and expulsion flights per month. At most, this is a capacity to fly out about 15,000 to 18,000 immigrants monthly. But because this includes expulsions of criminals and others from the interior of the United States, not just border arrests, the share of border crossers the government is able to fly out from the border is quite low. It also may not be possible for Border Patrol to detain someone long enough to transfer them to Immigration and Customs Enforcement for a flight out of the country.

It is not surprising that the government lacks the capacity to fly out this many immigrants from countries other than Mexico and the Northern Triangle because it has never in its history arrested so many immigrants from elsewhere. In October 2022, a majority of immigrants arrested at the border were from these countries.

Table 1 shows the breakdown of arrests by country of origin and the number of Title 42 arrests (and expulsions). Setting aside Mexico and the Northern Triangle, immigrants from Cuba, Venezuela, and Nicaragua lead the way. These countries led by authoritarian governments have limited or no diplomatic relations with the United States and prevent easy removal flights to those countries. After those, Colombia, Ecuador, and Brazil form a sort of second tier.

The administration has managed to greatly reduce Ecuadorian and Brazilian crossings by convincing Mexico to require visas for travelers for these two countries, so they cannot fly to Mexico to cross into the United States. It tried the same approach with Venezuela, but Venezuelans switched to traveling by land. Colombia and Peru have an international agreement with Mexico that prevents this approach from being applied to them.

While this post has focused on Border Patrol arrests of people crossing illegally, Title 42 has also been applied to people who cross legally into the United States at U.S.-Mexico land ports of entry to request asylum. In 2022, the Biden administration has started to permit more people to apply for an exception to Title 42 so they can enter at ports of entry. But processing is still far below its peak when it decided to admit all Ukrainians at the U.S.-Mexico border. Only about 10 percent of crossers are permitted to cross legally in this way.

In 2022, the administration has placed a heavy emphasis on processing Haitians for asylum at ports of entry who had a long tradition of requesting asylum at the ports of entry before the Trump administration stopped processing them. This initiative has transformed the flow of Haitian crossers from over 99 percent illegal to over 98 percent legal. But setting aside Ukrainians, other nationalities have not had a similarly open process to them. The process requires a referral from a nonprofit organization at the border, and approvals are arbitrary and based on the government’s willingness to accept them.

The Title 42 policy has failed on its own terms. The number of crossers has increased, and the border is more disorderly than it was before. A better policy would focus on legal avenues for people to apply to travel to the United States. The administration is already showing how effective that approach can be with Ukrainians and Haitians. In October, it created a new process for Venezuelans. It is increasing H‑2B visas for the Northern Triangle countries. But much more can and should be done to make immigration legal, safe, and orderly.