It’s nice to combine a long weekend with a chance to pick up some bargain kitchenware; but outside of that, what’s the point of Presidents’ Day? Modern presidents are ubiquitous and inescapable: hectoring us from above every treadmill at the gym and meddling in every area of American life, from where we get our groceries to which bathroom we’re allowed to use. It’s not as if we’ll forget they exist without setting aside a special day to salute them. Besides, neither the individual presidents we inflict on ourselves every four to eight years nor the institution itself is worth celebrating.

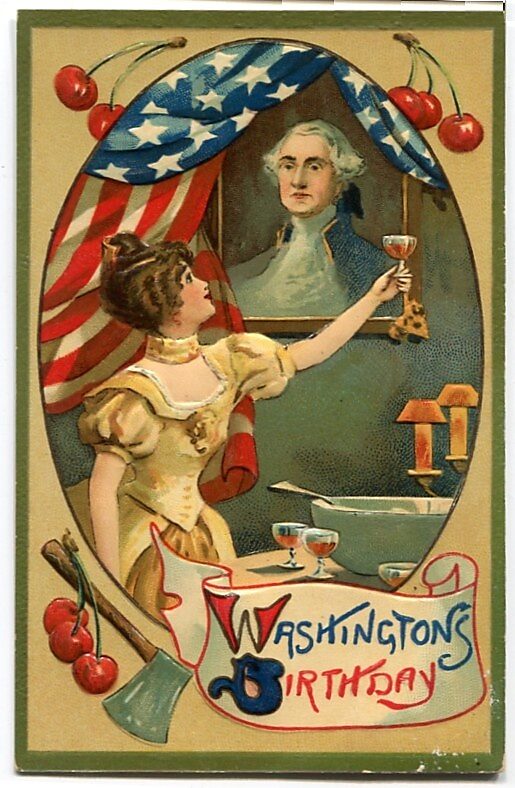

It’s some consolation, then, that, at the federal level at least, there’s no such thing as “Presidents’ Day.” The official designation for the third Monday in February is “Washington’s Birthday.” That’s been the case since one of our less meddlesome presidents, bewhiskered nonentity Rutherford B. Hayes, signed the holiday into law in 1879.

Granted, it hasn’t been observed on the first president’s actual birthday, February 22, since the Nixon administration. With the 1968 Uniform Monday Holiday Act, Congress sacrificed accuracy in order to give Americans the benefit of three-day weekends, stipulating that “Washington’s Birthday” would be observed on February’s third Monday.

Still, every so often, some civic-minded busybody insists that it’s presidents—or worse, the presidency in general—that we should be commemorating. In the late ‘90s, for example, Sen. Dick Durbin (D‑Ill.) introduced a bill (cosponsored by Ted Kennedy and Tom Daschle) to redesignate “the legal public holiday of Washington’s Birthday as Presidents’ Day … in recognition of the importance of the institution of the Presidency and the contributions that Presidents have made to our nation’s development and the principles of freedom and democracy.”

Bah, humbug. Our presidents—especially the “great” ones—have more often trampled those principles than upheld them. When scholars rank the presidents, their “Top 10” lists typically include a Murderers’ Row of chief executives whose “contributions” to freedom and democracy include Japanese internment, Indian removal, unconstitutional wars, illegal spying, and the imprisonment of peaceful dissenters.

And while there’s no denying “the importance of the institution,” what freedom and self-government we still enjoy persists in spite, not because of, our presidential system. In a pioneering 1990 article, “The Perils of Presidentialism,” the political scientist Juan Linz argued that presidential systems—those that feature a powerful executive, directly elected by the people and serving for a fixed term—are prone to catastrophic breakdowns and degeneration into autocratic rule. By combining the roles of head of state and head of government in one figure, such systems encourage presidents to imagine themselves the living embodiment of the popular will. The president “becomes the focus for whatever exaggerated expectations his supporters may harbor,” Linz writes, and in turn may “conflate his supporters with ‘the people’ as a whole.”

Worse still, the rigidity of presidential terms makes it far harder to throw the bums out if they go rogue. Prime ministers serve at the pleasure of parliament and can even be replaced by their own party. But in all of U.S. constitutional history, we’ve never successfully used the impeachment process to remove a president (Nixon quit). Unless he’s catatonic or certifiable, we’re stuck with him for the duration.

Presidentialism’s perils have been especially apparent throughout Latin America, where populist despots invoke “democracy” in the service of one-man rule. But it’s a flawed scheme wherever it operates. In his 2014 book The Once and Future King, the legal scholar F.H. Buckley found that “presidentialism is significantly and strongly correlated with less political freedom,” and concluded that “what makes America exceptional is that, for more than two hundred years, it has remained free while yet presidential.” Maybe our luck will continue to hold, but that’s no reason to applaud an institution that, all things considered, wasn’t the Founding Fathers’ best work.

There’s a better case for returning to the holiday’s original purpose: recognition of George Washington, a president distinguished by his reluctance to wield power: the proverbial “Man Who Would Not Be King.”

The Constitution “must mark the line of my official conduct,” Washington noted at the beginning of his administration, and frequently demurred when unsure of the extent of his lawful power—even hesitating to launch offensive action against hostile Indian tribes.

He was a model of restraint in his personal conduct as well. As a teenager, Washington copied in his own hand 110 precepts on etiquette: “The Rules of Civility and Decent Behavior in Company and Conversation.” Some of those rules make for an illuminating contrast with the deportment of our current chief executive:

- Washington’s “Rules”: “Undertake not what you cannot perform but be careful to keep your promise.”

Trump: “If I win, all of the bad things happening in the U.S. will be rapidly reversed!”

- Washington’s “Rules”: “Be not immodest in urging your friends to discover a secret.”

Trump: “check out sex tape”

- Washington’s “Rules”: “When in company, put not your hands to any part of the body not usually discovered.”

Trump: “You can do anything. Grab ’em by the…” er, you know.

Henry Adams famously remarked that the descent from “President Washington to President Grant was alone evidence enough to upset Darwin.” He didn’t know the half of it. This Monday, on Washington’s Birthday (observed), take a moment to contemplate our long downhill slide—and worry about where we’ll end up.