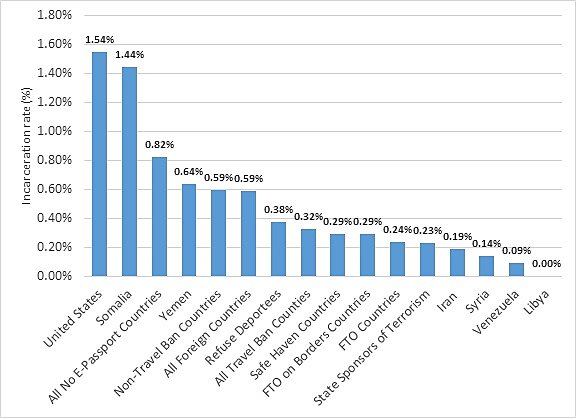

The Trump administration’s newest argument in favor of the travel ban is that foreigners from the eight banned countries are disproportionately crime prone. Indeed, the administration’s new travel ban proclamation references “criminal” risks or “public safety threats” from foreigners from those eight banned countries a total 34 times. However, the incarceration rate for people from the travel ban countries is below that of native-born Americans and foreign-born folks from countries that were not on the travel ban list.

The average incarceration rate for those born in the travel ban countries is 0.32 percent, almost half of the 0.59 percent incarceration rate for those born abroad in non-travel ban countries (Figure 1). There are some exceptions by nationality-at-birth as Somalis have a high incarceration rate just below that of native-born Americans and the Yemeni rate is right above that of the non-travel ban countries. The numbers of people from Chad and North Korea who are incarcerated or in the population as a whole are not reported.

The government has many categories of countries that are marked as terrorist threats. These categories of countries are divided by their level of sharing of immigration and travel security with the U.S. government, the operation of foreign terrorist organizations on their soil, whether they are sponsors of terrorism, whether they border terrorist safe havens, if they refuse to accept deportees, and other criteria. The incarceration rate for folks born in the countries in these categories varies dramatically (Figure 1).

The foreign-born incarceration rate for nations without E‑Passports is 0.82 percent—the worst showing of these categories. The foreign-born incarceration rate for those from countries that refuse deportees is 0.38 percent, barely above those of the travel ban countries. The foreign-born incarceration rate for state sponsors of terrorism, terrorist safe havens, nations that border countries with foreign terrorist organizations, and countries with foreign terrorist organizations operating on their soil are all below the average incarceration rate for the travel ban countries. Of the eight countries, only Yemen and Somalia have incarcerations above those categories of countries.

Figure 1

Incarceration Rates by Country of Origin, Ages 18–54

Source: Authors’ analysis of the 2015 1‑year American Community Survey data.

We calculated the figures from the 2015 1 year American Community Survey (ACS) sample from IPUMS. It focuses on people between the ages of 18 to 54 who are incarcerated in the United States, their incarceration rates, and their demographics. The ACS inmate data is reliable because it is ordinarily collected by or under the supervision of correctional institution administrators. These estimates include all foreign-born people who are incarcerated regardless of legal status.

One weakness of the ACS data is that we cannot help but over count the incarceration rate. That is because we can only look at those who are in group housing, a category that includes adult correctional facilities, mental health hospitals, homes for the handicapped, and elderly care institutions. We partly adjusted for this by narrowing the age range to 18–54 so as to exclude many inmates in mental health and retirement facilities. Still, this method over counts by about 800,000 prisoners.

Even with the overcount of prisoners in adult correctional facilities, the incarceration rate for foreign-born people from the travel ban countries is below the average of non-travel ban countries, all foreign countries, countries that do not issue E‑Passport, and those born in the United States. The incarceration rate of people born in the travel ban countries is not a compelling justification for the travel ban.

Special thanks to Michelangelo Landgrave for crunching most of the numbers that went into this blog post.