Yesterday, two men drove a van into a crowd in Barcelona, Spain and killed more than a dozen people and injured many more in what Spanish authorities are claiming is a terror attack. Spanish authorities may have also prevented another attack later in that day and believe these are linked to a recent explosion. Not all of the facts are public yet and we will learn more in the coming days, but Spain’s experience with terrorism can at least put what happened into perspective.

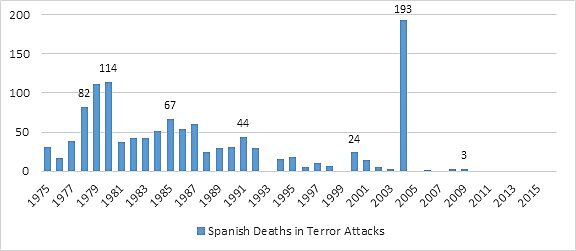

According to data from the Global Terrorism Database at the University of Maryland and the RAND Corporation, terrorists murdered 1,209 people in Spain from 1975 through the end of 2016 (Figure 1). The spike in deaths in 2004 was the result of a major al Qaeda attack on the Madrid subway system that murdered 192 people. Only the United Kingdom has suffered more from terrorism during that time with 2,359 total murders. There were also 4,738 injuries in terror attack in Spain during this 42-year time span.

Figure 1

Murders in Spanish Terrorist Attacks by Year, 1975–2016

Sources: Global Terrorist Database and RAND Corporation.

From 1975 through 2016, a Spaniard’s chance of dying in a terrorist attack was about 1 in 1.43 million per year (Table 1). Spain was the fourth most victimized country on the list by that measure and about 2.6 times as deadly as the United States. Basque separatists are responsible for most of the terrorist deaths in Spain since 1975 but Islamists have been the most deadly since 2004. Basques are not immigrants and their language is so different from other European tongues than many linguists have theorized that it predates the introduction of Indo-European tongues on the continent of Europe. Thus, most of these deaths were not caused by recent immigrants.

Terrorism in Spain has trended generally downward since 2000. Since then until 2016, 247 people have been killed in terrorist attacks on Spanish soil which translates to a 1 in 3.1 million chance per year of dying in that way. In 2012, there were 364 homicides in Spain which translate into a 1 in 128,729 chance of being murdered in a non-terrorist homicide that year. Spain’s homicide rate is so low that terrorism actually looks like a serious hazard by comparison.

Table 1

Annual Chance of Dying in a Terror Attack and the Number of Terrorist Murders in European Countries, 1975–2016

|

Country |

Terrorist Murders |

Annual Chance of Dying in Terror Attack |

| Croatia |

248 |

1 in 765,052 |

| Cyprus |

38 |

1 in 975,361 |

| United Kingdom |

2,359 |

1 in 1,057,248 |

| Spain |

1,209 |

1 in 1,432,847 |

| Greece |

215 |

1 in 2,069,185 |

| Ireland |

68 |

1 in 2,396,564 |

| Malta |

4 |

1 in 3,977,889 |

| France |

489 |

1 in 5,030,009 |

| Belgium |

73 |

1 in 5,932,942 |

| Italy |

317 |

1 in 7,643,464 |

| Bulgaria |

27 |

1 in 12,810,844 |

| Austria |

23 |

1 in 14,605,254 |

| Portugal |

26 |

1 in 16,424,666 |

| Netherlands |

27 |

1 in 24,047,998 |

| Germany |

139 |

1 in 24,208,884 |

| Finland |

8 |

1 in 26,776,608 |

| Sweden |

13 |

1 in 28,499,047 |

| Estonia |

2 |

1 in 29,982,906 |

| Slovakia |

7 |

1 in 31,607,066 |

| Latvia |

2 |

1 in 50,301,214 |

| Denmark |

4 |

1 in 55,645,834 |

| Hungary |

6 |

1 in 72,048,567 |

| Czech |

6 |

1 in 72,509,981 |

| Slovenia |

1 |

1 in 82,598,090 |

| Lithuania |

1 |

1 in 143,165,024 |

| Poland |

7 |

1 in 225,306,754 |

| Romania |

4 |

1 in 231,493,613 |

| Luxembourg |

zero |

zero |

Sources: Global Terrorist Database, RAND Corporation, United Nations, and Author’s Calculations.

Some pundits argue that that chance of dying in terrorism is too high and that people should be willing to give up some freedoms in exchange for more security. They only sometimes mention what freedoms we should surrender and how such a move could lead to more security. They also rarely consider the costs of giving the government extra power, especially costs to our safety.

The misconception that safety is binary—it is either perfect safety or perfect danger—is on full display in the debate over security and freedom. The real question is what specific freedoms or other costs are Spaniards, or others, are willing to endure by increasing the size and power of their governments and reducing their own civil liberties in order to diminish the already low annual chance of dying in a terrorist attack to 1 in 4 million a year, 5 million a year, or to some other number. Even assuming that there is no way more government power can backfire and decrease security, there is a point where the costs of extra security are not worth the benefits. In the United States, we are well past that point. Spain shouldn’t similarly overreact.