Kim Jong-un threw a big military parade earlier today, reminding the world of his military power on the eve of the Pyeongchang Winter Olympics’ opening ceremony. Compared to the massive annual parade that takes place on April 15th (the anniversary of Kim Il-sung’s birth), today’s parade was smaller and less significant, though it did feature some interesting missile systems.

The first missile system of note was a new type of close- or short-range ballistic missile (C/SRBM) that, at first glance, looks similar to the Russian-made Iskander‑M SRBM.

(New type of North Korean C/SRBM, February 8, 2018. Source: YouTube)

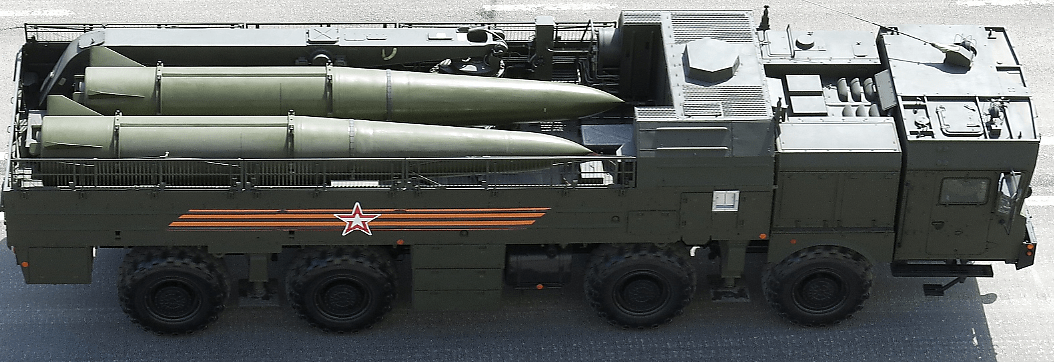

(Iskander‑M SRBM system. Source: Wikipedia Commons)

Like the Iskander, the new North Korean system carries two missiles side-by-side in a four axle transporter-erector-launcher (TEL) vehicle. Another similarity of the two systems is fuel type: most C/SRBMs use solid rocket fuel. Although the type of fuel used in the new North Korean missile system cannot be determined from the parade video alone, it would be very unusual for a missile of its size to not use solid fuel.

The combination of the TEL and solid rocket fuel implies that the North Korean system is highly mobile and can be launched on much shorter notice than Pyongyang’s liquid-fueled Scud missiles. The new missile may have a shorter range and lighter payload than the larger Scud, but the smaller logistical footprint and shorter launch time of the new system could offer important tactical advantages.

However, imagery analysts have noticed some external features of the new missile that are inconsistent with the design of the Iskander. Writing for NK Pro, Scott LaFoy says, “It may also be the case that this is a heavily modified Tochka system [another Russian missile]…[but] the imagery is insufficient for building a confident assessment.” Moreover, while the Iskander‑M is a very accurate SRBM, the parade footage does not provide any definitive information about the accuracy of the North Korean missile.

Replacing or supplementing the Scud-based SRBM force with solid-fueled, highly-accurate C/SRBMs would be an important strategic development for North Korea. However, the images from the recent parade do not provide much information about North Korea’s the capabilities of the new missile system beyond some general inferences.

The parade also featured North Korea’s two inter-continental ballistic missiles (ICBMs), the Hwasong-14 and Hwasong-15. This is the first time that either missile has appeared in the parade, but both were successfully flight tested in 2017, so the missiles themselves don’t come as a surprise.

(Hwasong-14 on flatbed tractor-trailer, February 8, 2018. Source: YouTube)

However, the vehicles that carried the ICBMs are notable. Instead of being carried by the vehicle used during its flight tests, the Hwasong-14 was mounted on a flatbed trailer being towed by a truck. This tractor-trailer configuration was previously seen last April, but in that parade the trailer featured a large canister and equipment for erecting the canister—akin to China’s DF-31A ICBM. Both the canister and erector equipment were absent in the recent parade. The lack of a canister and erector, as well as the fact that the Hwasong-14’s rocket engine was covered up, suggest that the tractor-trailer configuration seen in today’s parade was for display purposes only. The Hwasong-15 was carried by the TEL that was used in its November 2017 flight test, but only four TELs appeared in the parade.

(Hwasong-15 on TEL, February 8, 2018. Source: YouTube)

The number of TELs in today’s parade is important because it represents a key vulnerability in North Korea’s ICBM force. All of the North Korean vehicles capable of carrying ICBMs are based on Chinese-made heavy logging trucks that were modified by the North Koreans to carry missiles, but no more than six of these trucks have been seen at one time. Kim Jong-un recently claimed that North Korea is capable of indigenously producing more large TELs for its missile forces. The TEL for the Hwasong-15 does have one more extra axle than the original logging truck, and the presence of five Hwasong-15s at the parade shows that the North Koreans can successfully modify their existing capabilities. However, the parade offers no evidence to substantiate Kim’s claim that the country can manufacture new TELs.

Looking beyond the military hardware featured in the parade, it’s important to consider the message the parade was trying to convey. Inferring the strategic intent or signal behind such actions is a very difficult task, and there is probably no one right answer, but that probably won’t stop commentators from declaring the parade a threatening display of power meant to intimidate or divide the United States and South Korea. This is a plausible explanation, but there is another way to view the parade that is equally plausible.

The recent diplomatic rapprochement between North and South Korea is a welcome change from escalating rhetoric about military action that characterized much of 2017. The military parade, which was announced shortly after the beginning of North-South dialogue, may be intended as a signal to North and South Koreans rather than the United States. Kim may be the most important individual within North Korea, but he depends on several power structures within his government for support and legitimacy. Conducting a military parade in the midst of diplomatic talks between Pyongyang and Seoul shows these power structures that Kim is not negotiating from a position of weakness and that military options for defending and advancing North Korea’s interests are not being neglected. The potential message the parade sends to Seoul is a reiteration of Kim’s bottom line that talks will not lead to denuclearization or regime change.