There’s been a lot of heated discussion about various preferences, deductions, credits, shelters, and other loopholes in the tax code. Some of this debate has revolved around whether it is legitimate to refer to these provisions as “tax expenditures” or “subsidies.”

Michael Cannon vociferously argues that subsidies and expenditures only occur when the government takes money from person A and gives it to person B. On the other side of the debate are people like Josh Barro of the Manhattan Institute, who argues that tax preferences are akin to subsidies or expenditures since they can be just as damaging as government spending programs when looking at whether resources are efficiently allocated.

Since I’m a can’t-we-all-get-along, uniter-not-divider kind of person, allow me to suggest that this debate should be set aside. After all, we all agree that tax preferences can lead to inefficient outcomes. So let’s call them “tax distortions” and focus on the real issue, which is how best to eliminate them.

This is an important issue because both the Domenici-Rivlin Task Force and the Chairmen of the Simpson-Bowles Commission have unveiled plans that would reduce or eliminate many of these tax distortions and also lower marginal tax rates. That’s the good news.

The bad news is that their plans result in more revenue going to Washington. In other words, the tax increase resulting from fewer tax distortions is larger than the tax decrease resulting from lower tax rates. To put it bluntly, the plans would increase the overall tax burden.

Some argue that this is an acceptable price to pay. They point out, quite correctly, that lower tax rates will help the economy by improving incentives for productive behavior. And they also are right in arguing that fewer tax distortions will help the economy by improving efficiency. Seems like a win-win situation. What’s not to like?

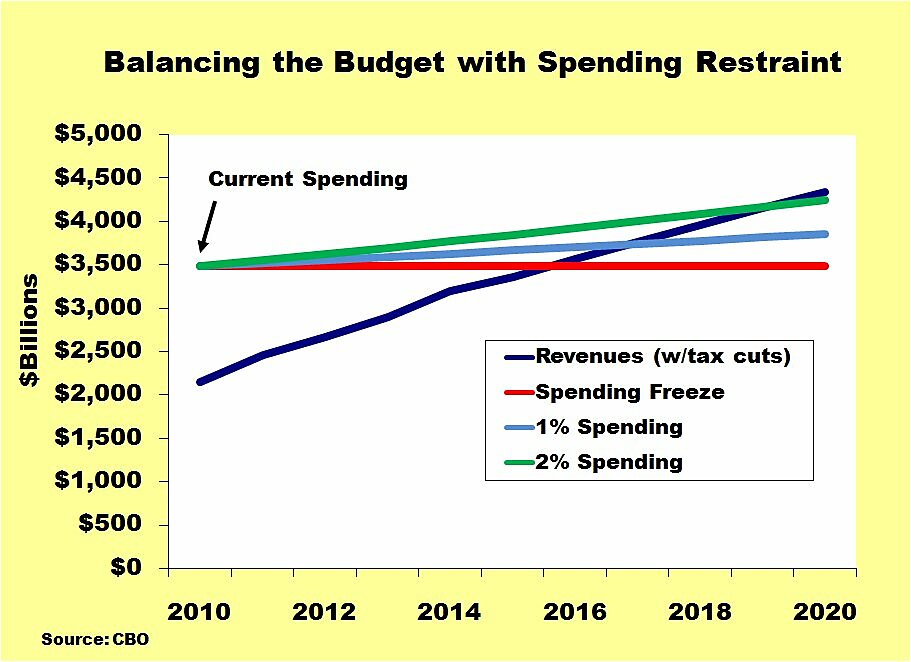

The problem is on the spending side of the fiscal ledger. The Simpson-Bowles Commission and the Domenici-Rivlin Task Force were charged with figuring out how to reduce red ink. We already know from Congressional Budget Office data, however, that we can balance the budget fairly quickly by limiting the growth of government spending. As the chart illustrates, the deficit disappears by 2016–2017 with a hard freeze and goes away by 2019–2020 if spending increases by two percent each year (and this assumes all the 2001 and 2003 tax cuts are made permanent).

If tax revenue is increased, that simply means that the budget gets balanced at a higher level of spending. And since government spending, at current levels and composition, hinders economic growth by diverting labor and capital to less productive (or unproductive) uses, any proposal that enables higher levels of government spending will further undermine economic performance.

It goes without saying (but I’ll say it anyhow) that this analysis is overly optimistic since it assumes that politicians actually will balance the budget. In all likelihood, as explained in today’s Wall Street Journal, any tax increase would probably be followed by even more spending. So if politicians raise the tax burden, we might still have a deficit of $685 billion in 2020 (CBO’s most-recent estimate assuming all programs are left on auto-pilot), but the overall levels of both spending and taxes would be higher. This modified cartoon captures this real-world effect.

This is why revenue-neutral tax reform, like the flat tax, is the only pro-growth way of eliminating tax distortions.