After completing months-long “top-to-bottom” review of the United States’ trade policy toward China, United States Trade Representative Katherine Tai announced yesterday that the Chinese government has failed to comply with the terms of the 2019 U.S.-China “Phase One” Agreement, but that the Biden administration will nevertheless maintain the U.S. tariffs intended to achieve changes in Chinese policy and to enforce the deal. The White House will instead seek talks with China in the coming days and reopen a process for U.S. importers to win an exclusion from said tariffs.

Although Tai’s comments are unsurprising, they’re disappointing for at least three reasons:

First, as I explained in August, there’s little doubt that the tariffs are hurting the U.S. economy:

[T]he tariffs that the Trump administration imposed on Chinese imports harmed U.S. consumers and manufacturers, deterred investment (mainly due to uncertainty), lowered U.S. GDP growth, and hurt U.S. exporters (especially farmers but also U.S. manufacturers that used Chinese inputs). At the same time, they did little to promote the reshoring of “essential industries” to the United States because global supply chains primarily shifted final assembly of covered goods to other foreign countries, not the USA.

Second, as Tai now admits, the U.S. tariffs haven’t changed China’s behavior or ensured compliance with the Phase One deal. The tariffs’ overall impact on the Chinese economy has been relatively muted – decreasing Chinese GDP by an estimated 0.29 percent – because China’s economy is relatively large; Chinese companies, foreign investors, and the Chinese government adapted; and increased tariff costs were mostly passed on to U.S. consumers. Indeed, as I noted last year, the agreement’s reliance on tariffs – instead of trade agreement’s traditional compliance incentives – set it up to fail:

[B]ecause the agreement is so one‐sided, China—the party making all of the concessions—has very little incentive to comply in order to maintain its agreement benefits (there are none) or encourage U.S. compliance (there’s nothing for the U.S. to comply with). Sure, the American market is valuable, and avoiding the deal’s collapse or potentially more tariff pain is an incentive, but most of the U.S. tariffs are still in place, and the ones that aren’t cover goods that the U.S. was, for economic, political and now public health reasons, desperately trying to avoid hitting in the first place.

Meanwhile, there are little to no reputational benefits for China to maintain the deal. U.S.-China tensions are approaching all‐time highs, so noncompliance and retaliation wouldn’t likely move the needle much at this point—especially since the other team is the one calling foul. There’s also little chance that other trading partners like the EU, Australia or Japan would care if the deal fell apart. In fact, they’d probably welcome it due to the deal’s radical rejection of international legal norms and the multilateral trading system (which most countries still vocally support), as well as its beggar‐thy‐neighbor terms that actually harm U.S. competitors in the Chinese market.…

As I added a couple months ago, moreover, current U.S. policy actually appears to have pushed China to double down on self‐sufficiency, distortive industrial policy, and nationalism more generally. And, of course, China’s hardline stances on human rights, Hong Kong, the South China Sea, and other issues have only gotten worse, not better, in the last few years.

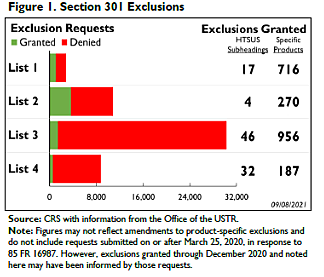

Third, while some U.S. importers might cheer the resumption of USTR’s tariff exclusion process, it too has thus far been underwhelming. For starters, exclusions were rarely granted:

As I’ve documented, moreover, the exclusion process itself has repeatedly been found to be both costly and rife with political favoritism and cronyism, enriching K Street lobbyists far more than the American companies begging for relief. In fact, a recent report from the Government Accountability Office “found that [USTR] didn’t fully document its internal procedures for deciding tariff exclusion requests or adequately explain its approval or denial of a request; didn’t document any of its internal procedures for deciding whether to extend tariff exclusions; didn’t have written procedures for the interagency portion of a review; and applied the limited rules it did have in an inconsistent and arbitrary way.”

So the tariffs have failed. The Phase One Deal has failed. And USTR Tai’s solution is to keep those things and resume a failed exclusion process.

Like I said, disappointing.