Student protesters at the College of William and Mary recently shut down a campus speaker from the ACLU invited (ironically) to speak about “Students and the First Amendment.” Students explained their shut down was in retaliation for the ACLU’s defense of white nationalists’ free speech rights in Charlottesville, Virginia where a white nationalist rally recently took place. What motivated the students?

The Black Lives Matter of William and Mary student group wrote on their Facebook page, where they live-streamed their shut down of the event: “We want to reaffirm our position of zero tolerance for white supremacy no matter what form it decides to masquerade in.” From these students’ perspective, the ACLU supporting someone’s right to say racist things was as bad as being a racist organization.

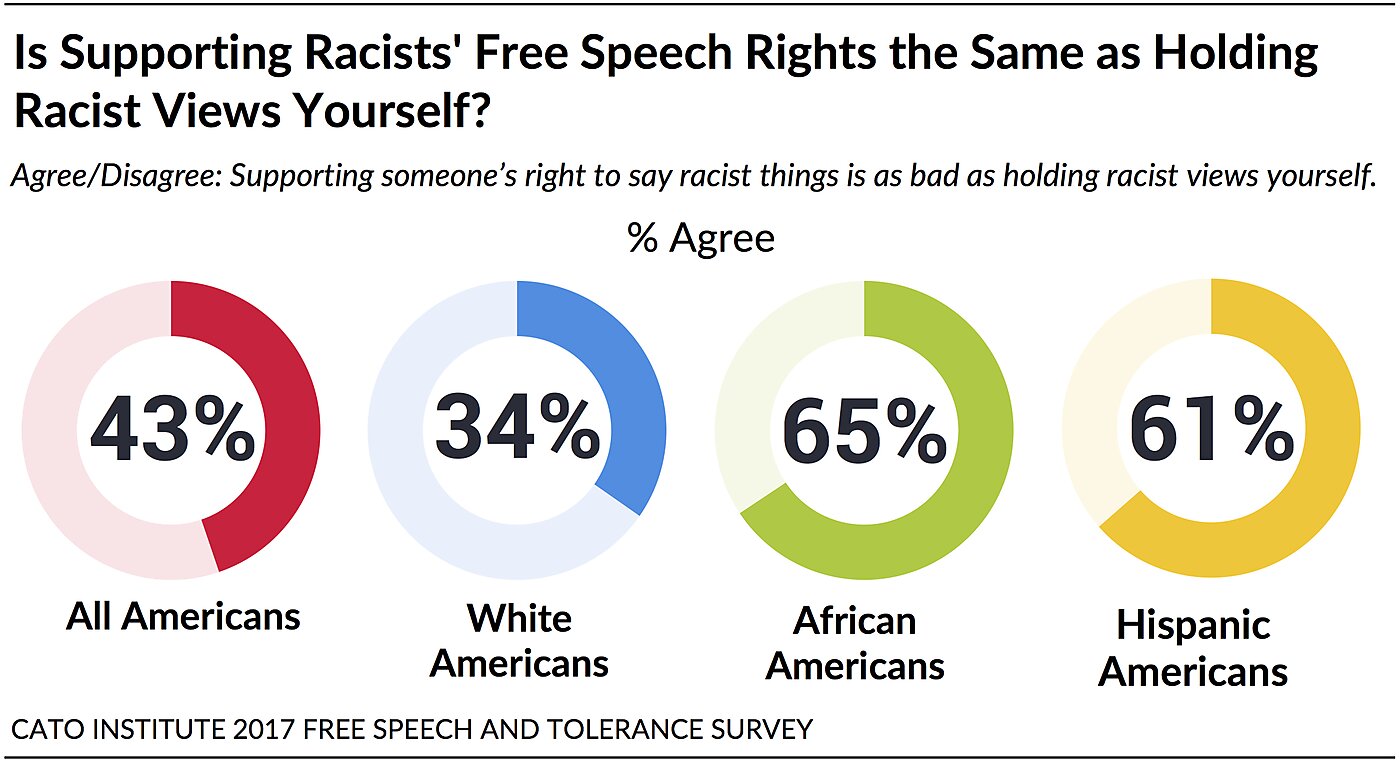

The Cato 2017 Free Speech and Tolerance Survey helps shed light on these students’ reasoning. First, nearly half (49%) of current college and graduate students believe that “supporting someone’s right to say racist things is as bad as holding racist views yourself.” This share rises to nearly two-thirds among African Americans (65%) and Latinos (61%) who agree. Far fewer white Americans (34%) share this view.

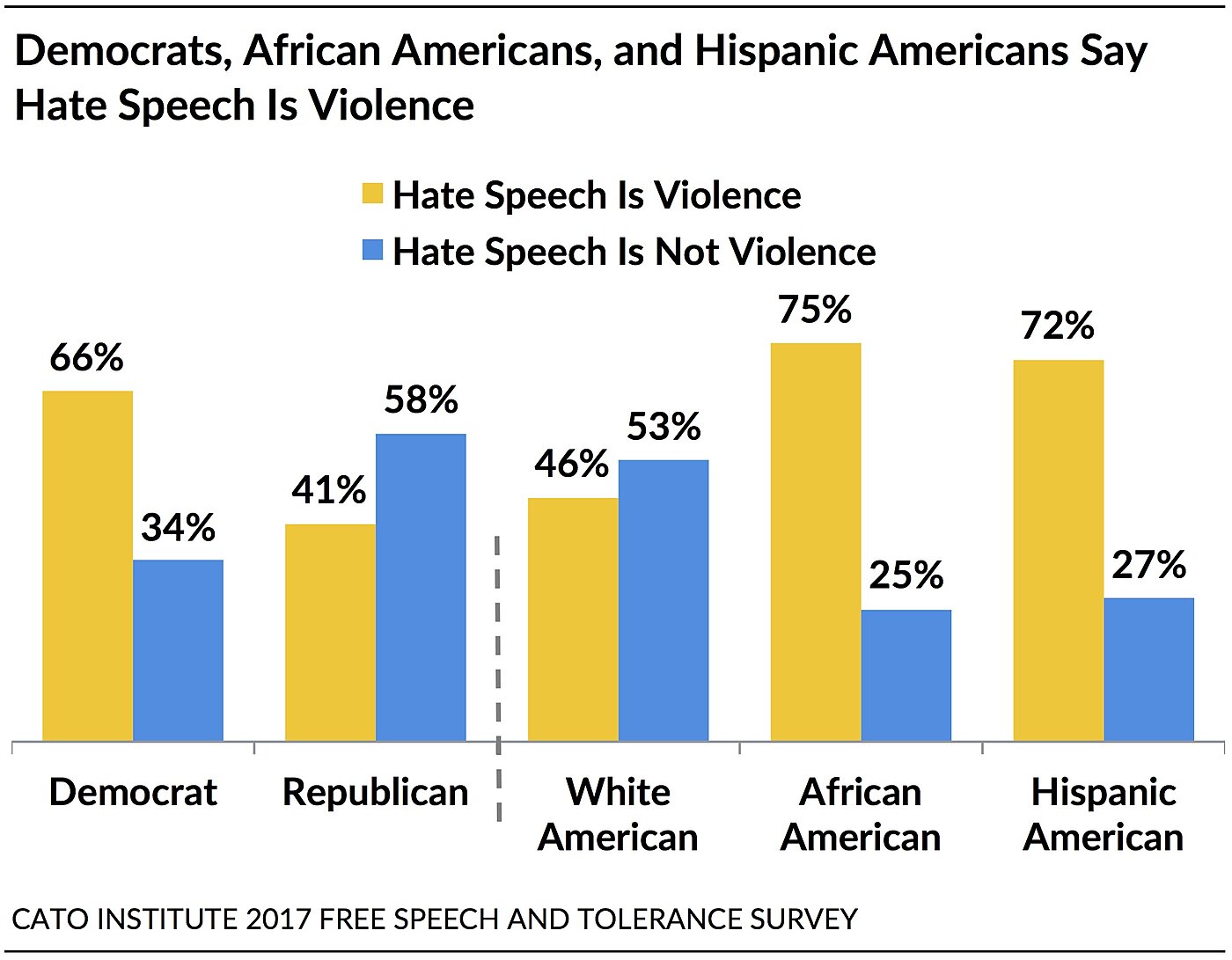

Next, a majority (55%) of current students and nearly three-fourths of African Americans (75%) and Latinos (72%) believe that hate speech is an act of violence. Conversely, 53% of whites believe it is not.

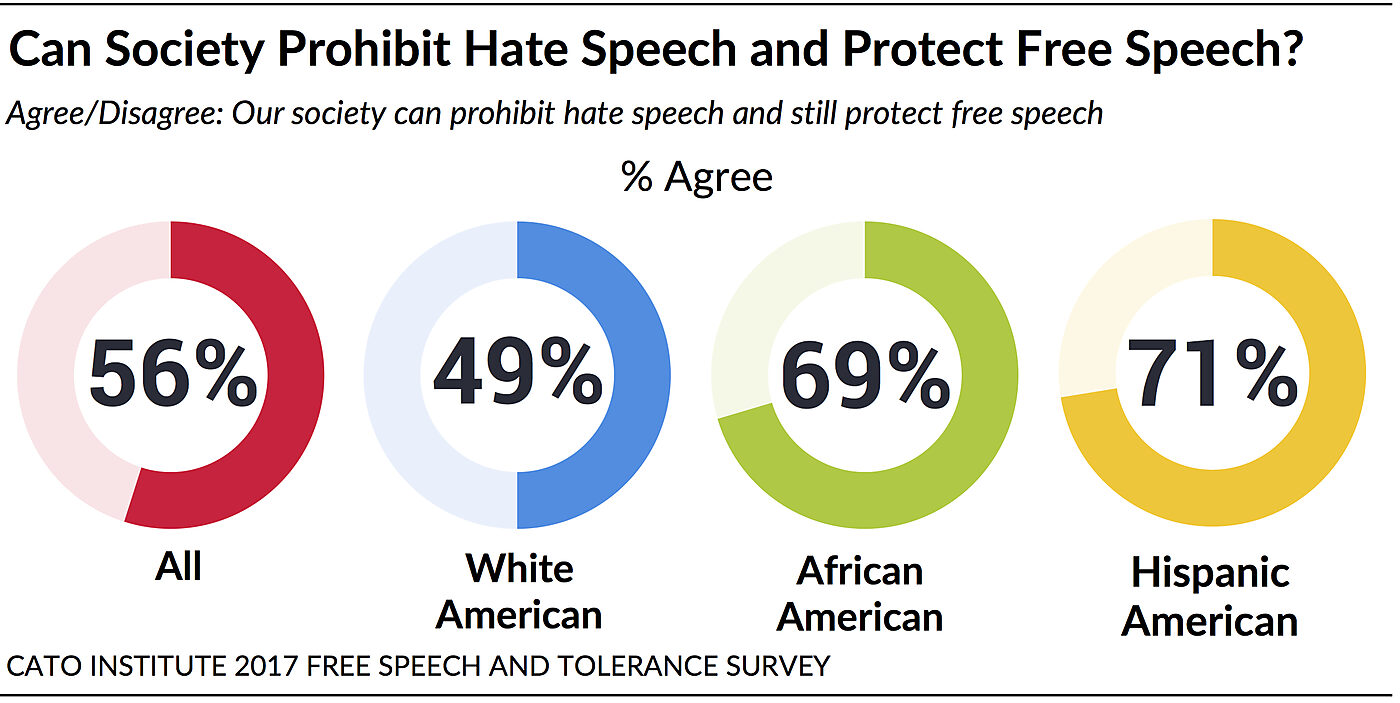

In addition, 62% of current students and 7 in 10 African Americans and Latinos believe that “our society can prohibit hate speech and still protect free speech.” White Americans are evenly divided on this question.

Taking these results together, it becomes clearer why the William and Mary students reacted as they did. From the students’ perspective, society is capable of protecting our First Amendment rights and curbing hate speech. If that’s true, why protect hate speech? Next, they believe hate speech is itself a violent act. Why would one want to enable violence against others? Consequently, many may conclude that anyone who tries to protect another’s right to engage in hate speech has nefarious intentions or is at least as bad as those espousing the hate. According to this view, protecting hate speech seems unnecessary and damaging. Thus, such a defense of free speech does not appear to be grounded in principle but rather a lack of empathy or even malice.

Understanding the assumptions behind the students’ logic allows for a more productive conversation. For instance, one might ask these students: is it really true that society can simultaneously ban hate speech and protect free speech? If so, how does society decide what speech is hateful and thus should be banned? Additional results from the survey demonstrate that Americans cannot agree what speech is hateful and offensive, which would make it difficult to regulate. This raises the next question: if society can’t agree what speech should be off limits, who gets to decide what speech is hateful and should be banned?

Answers to these questions are complicated and demonstrate why efforts to censor and regulate speech and expression are significantly problematic.

Sign up here to receive forthcoming Cato Institute survey reports

The Cato Institute 2017 Free Speech and Tolerance Survey was designed and conducted by the Cato Institute in collaboration with YouGov. YouGov collected responses online August 15–23, 2017 from a national sample of 2,300 Americans 18 years of age and older. The margin of error for the survey is +/- 3.00 percentage points at the 95% level of confidence.