A Wall Street Journal article on an upgrade to a Midwest rail line illustrates the shortcomings of pumping tax dollars into passenger rail.

Amtrak’s route from Chicago to St. Louis would seem an ideal place for the U.S. to adopt high-speed rail such as in Europe and Asia, where passenger trains can race along at 200 miles an hour. The stretch in Illinois is a straight shot across mostly flat terrain.

In fact, a fast-rail project is under way in Illinois. Yet the trains will top out at 110 mph, shaving just an hour from what is now a 5½-hour train trip.

After it’s finished, at a cost of about $2 billion, the state figures the share of people who travel between the two cities by rail could rise just a few percentage points.

Behind such modest gains, for hundreds of millions of dollars spent, lie some of the reasons high-speed train travel remains an elusive goal in the U.S.

Laying dedicated track is expensive but relying on existing track owned by freight rail firms limits speed and on-time performance. The latter approach also undermines the freight rail system, which is an efficient and powerful engine of the U.S. economy.

Illinois didn’t have the money, or the right-of-way, to lay tracks that would be exclusively for a high-speed service. So its fast passenger trains will have to share the track with lumbering freight trains.

“To build the kind of infrastructure that is stand-alone—that is, just for high-speed passenger rail—it is just absurdly expensive and just takes years and years and years to get through the permitting and environmental process,” said Randy Blankenhorn, who was Illinois’s transportation secretary until this year.

“Land acquisition alone [would] take half a decade,” he said. “If we were to have said from the beginning, right off the bat go to 200-mile-an-hour service, we’d still be in the implementing and design phase.”

Illinois settled for weaving improvements along the route and rebuilding an existing single-track line that is owned by freight railroads. In effect, it chose higher-speed rail rather than actual high-speed.

… The Illinois rail project has consisted of making major improvements to the route on which Amtrak provides service. Work started in September 2010 and was supposed to finish in seven years. A federal mandate requiring trains to have an automatic mechanism to prevent certain accidents helped push back the timeline.

It has been a monumental undertaking that required dealing with railroad companies, cities and landowners, said John Oimoen, deputy director of railroads in the state transportation department. More than 300 road crossings had to have separate agreements covering upgrades or closures.

By late 2015, agency officials feared the project was dead, simply because so many deals needed to be negotiated before a deadline to spend the federal grant. The agency ultimately assigned its highway real-estate department to help finish the project.

Upgrading road crossings often meant rebuilding them, from drainage pipes up, to smooth passage for faster trains. Two extra signal arms were added to many crossings to keep drivers from going around them.

Another problem is federal micromanagement. Anything involving federal subsidies includes layers of regulations, which adds costs and delays.

[Illinois] also faced years of delays in getting new rail cars. Nippon Sharyo of Nagoya, Japan, landed a contract in 2012. Because the federal grant that funded the work required cars to be built in the U.S. from U.S.-made parts, the Japanese company expanded a 460,000-square-foot factory in Rochelle, Ill., and rebuilt its supplier network.

The company struggled to adapt designs and failed U.S. crashworthiness tests. In 2017 it withdrew from the contract and later closed the plant, meaning a side benefit Illinois hoped for—local jobs assembling rail cars—fizzled. The work moved to a Siemens AG facility in California.

Amtrak is plagued by lousy customer service. Trains do not run frequently and they have a poor on-time record.

Heidi Verticchio takes the train a few times a week between her home in Carlinville, Ill., north of St. Louis, and Bloomington-Normal, where she directs a speech and hearing clinic for Illinois State University. Because the trains don’t run frequently enough, she often has to drive the 120 miles when she needs more flexibility.

A higher speed won’t mean Ms. Verticchio will be taking the train more often. She estimates it might cut 10 to 15 minutes from her ride.

“It’s not going to make any difference,” she said.

Most of the Chicago-St. Louis train corridor remains a single track. Freight railroads Union Pacific and Canadian National own most of the route. They coordinate all traffic, including passenger trains.

In the year that ended with November, according to an Amtrak report, Canadian National caused 1,672 minutes of delay per 10,000 Amtrak train-miles logged on the route. Union Pacific caused 1,036 minutes of delay per 10,000 Amtrak train-miles, Amtrak said. Both exceeded Amtrak’s target of 900.

The report attributed about two-thirds of the delays to “freight-train interference.” It found that 73% of rail passengers arrived on time, but for those who faced delays, these averaged 45 minutes.

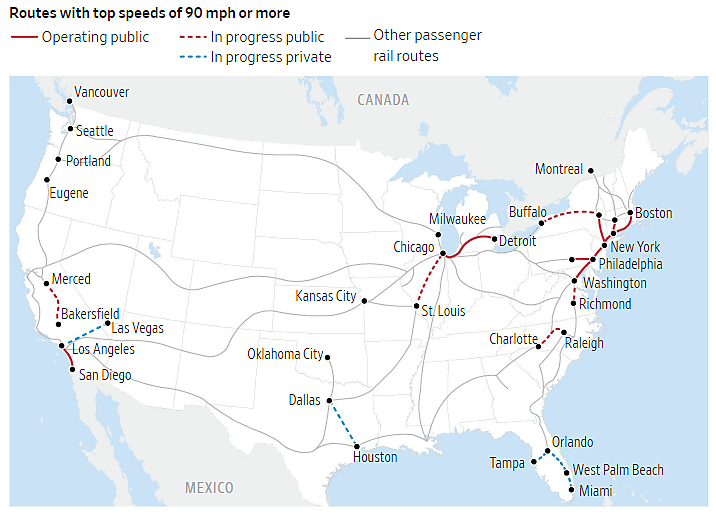

Finally, U.S. passenger rail is run by the government There is more private-sector involvement abroad, which is a better approach. So I agree with Puentes that the Florida and Texas projects bear watching.

Robert Puentes, president of the Eno Center for Transportation in Washington, notes that the U.S. has used just one approach to passenger rail since the 1970s, Amtrak. The government-owned corporation was cobbled together from remnants of major railroads’ passenger services. It is funded through fares and state and federal subsidies.

European rail networks feature a mix of government and business owners and operators. Mr. Puentes said new investor-owned passenger rail ventures in Florida and Texas bear watching.

More on Amtrak here.

Romance of the Rails can be ordered here.