A new paper that examined the effect Uber had on crime in 150 cities and counties from 2010–2013 reveals that Uber lowers the rate of DUIs and fatal vehicle crashes. This is not an especially surprising finding given that Uber, like other ridesharing companies, offers a convenient way for those who’ve had a few drinks to get a sober ride home. Interestingly, the paper’s authors, Providence College’s Angela K. Dills and Stonehill College’s Sean Mulholland, also found that the introduction of Uber is followed by a decline in arrests for assault as well as an increase in vehicle theft. On balance, Dills and Mulholland’s paper ought to reassure those who are concerned about ridesharing safety.

Uber’s effects on drunk-driving have been one of the technology company’s strongest talking points. Last year, Uber teamed up with Mothers Against Drunk Driving and issued a report, which claimed that Uber’s entry into Seattle was associated with a 10 percent reduction in DUI arrests. During debates on ridesharing in Austin, Texas, Travis County Sheriff Greg Hamilton noted that while the causal relationship between Uber’s arrival and a reduction in DWI arrests “requires more study,” DWI arrests had fallen 16 percent in 2014, the year after Uber came to Austin, and in 2015 DWI arrests declined by 23 percent.*

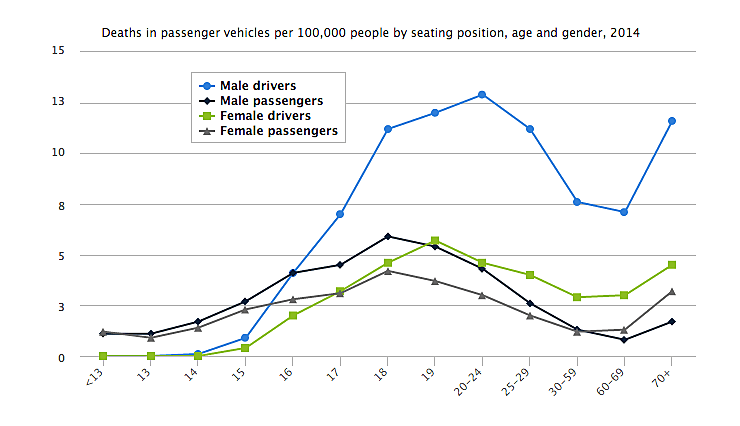

According to Dills and Mulholland, “For each additional year of operation, Uber’s continued presence is associated with a 16.6 percent decline in vehicular fatalities.” The reduction in fatal vehicle crashes prompted by Uber’s arrival shouldn’t be attributed solely to fewer drunk people driving. A recent Pew survey found that 28 percent of 18–29 year-old have used a ridesharing services like Uber, more than another other age group. As the graph from the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety below shows, this an age group that is comparatively very prone to fatal car accidents.

Not only is there a strong indication that Uber reduces drunk driving, it’s also a platform very popular among some of the country’s most dangerous drivers.

The decline in arrests for assault is an intriguing finding, and Dills and Mulholland write that this may be because Uber cuts wait-times for passengers, thereby reducing their chance of being assaulted on the street:

Wait times are also likely to be lower because ride-sharing applications can quickly adjust prices in response to changes in the number of riders and drivers. Potential ride-share passengers do not need to physically search for a vehicle as they do for a taxi. This reduces opportunities for them to become the victim of a street crime. Potential passengers can also leave on short notice. This may reduce assaults.

Perhaps the most interesting of Dills and Mulholland’s findings is that an increase in vehicle thefts follows Uber’s arrival in an area, “reflecting more than 100 percent increases at the mean.” Dills and Mulholland suggest that this could be because of “an increased propensity for Uber passengers to leave personal vehicles parked in public locations.”

I and others have argued that ridesharing services such as Uber should be allowed to compete against traditional market incumbents. Uber is a popular service that allows users to efficiently find rides at times and places where it is inconvenient to find taxis. Dills and Mulholland’s paper shows that not only can Uber offer a valuable service to its users, it can save lives as well.

*For the difference between a DUI and DWI under Texas law see this explainer from Johnson, Johnson & Baer, a Houston-based DWI law firm. http://www.dwi-texas.com/what-is-the-difference-between-a-dui-and-a-dwi-under-texas-law/