A recent randomized controlled trial found that the number of complaints against police fell dramatically after officers were outfitted with body cameras. It is the latest piece of research suggesting that police body cameras have a positive effect on police-citizen interactions.

The study, headed by the University of Cambridge’s Institute of Criminology, studied complaints against police in seven sites in two countries. The departments involved in the study were in areas such as the English Midlands, Cambridgeshire, California, and Northern Ireland. Researchers examined 4,264 officer shifts over roughly 1.5 million hours. In the 12 months before the trial began there were 1,539 complaints filed against police in the seven sites. After 12 months of taking part in the trial there were 113 complaints, a reduction of 93%.

Officers involved in the study were told to adhere to two policies that are not required by many departments: 1) officers wearing body cameras “had to keep the camera on during their entire shift,” and 2) those same officers had to “inform members of the public, during any encounter, that they were wearing a camera.”

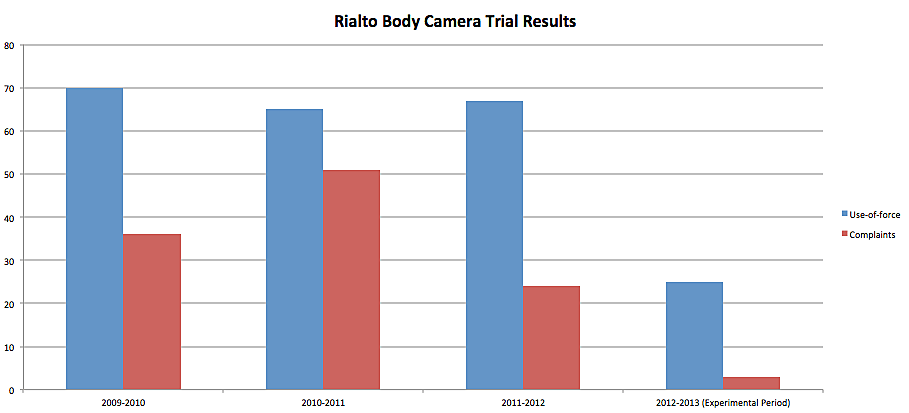

The study’s findings are similar to an often-mentioned trial that took place in Rialto, California, which also found that the outfitting of officers with body cameras was followed by a significant reduction (87.5%) in complaints.

Speaking about the most recent study, Cambridge University’s Barak Ariel, who oversaw the Rialto trial, said, “I cannot think of any [other] single intervention in the history of policing that dramatically changed the way that officers behave, the way that suspects behave, and the way they interact with each other.”

Interestingly, the researchers found that complaints fell for officers who weren’t wearing body cameras as well as those who did. According to the researchers this may be because of “contagious accountability”:

We argue that that BWCs affect entire police departments through a process we label contagious accountability. Perhaps naively, we find it difficult to consider alternatives to the treatment effect beyond the panopticonic observer effect when the reduction in complaints is by nearly 100%. Whatever the precise mechanism of the deterrence effect of being watched and, by implication, accountability, all officers in the departments were acutely aware of being observed more closely, with an enhanced transparency apparatus that has never been seen before in day-to-day policing operations. Everyone was affected by it, even when the cameras were not in use, and collectively everyone in the department(s) attracted fewer complaints.

As the researchers note, this “contagious accountability” effect comes with some caveats:

There is, however, a caveat associated with this conclusion, which is important for future experiments on BWCs. It is not the camera device alone that caused the contagious accountability, but rather a two-stage process. First, the treatment effect incorporated the camera as well as a warning at the beginning of every interaction that the encounter was being videotaped. We urge practitioners to acknowledge that the verbal warning, which our protocol dictated should be announced as soon as possible when engaging with members of the public, is a quintessential component of the treatment effect. It primed both parties that a civilized manner was required and served as a nudge to enhance the participants’ awareness of being observed. Without the warning, the effect might easily have been reduced or failed to materialize.

The second element to the process is the need for affirmation that the videotaped footage can be used. People may be aware of CCTV or bystanders filming the encounter but still conduct themselves inappropriately, believing the camera to either not be recording or not monitoring their demeanor. Without the actualization of the warning, transgressors may be quick to assume that the threat of apprehension and risk of sanctioning are not real. Therefore, the fact that the officially collated, recorded footage can be used against the participants moves this intervention from being a “toothless policy” (Ariel, 2012, p. 57) into an effective technological solution.

Although the recent study and the Rialto study did reveal encouraging findings, not all cities have seen such dramatic falls in complaints following body camera deployment. Nonetheless, the recent latest findings ought to encourage citizens and law enforcement officials alike to support police body cameras. Body cameras can, with the appropriate policies enforced, provide some much-needed increase in transparency and accountability in law enforcement while also helping to exculpate officers falsely accused of wrongdoing.