President Biden plans to tap the Strategic Petroleum Reserve (SPR) for a million barrels a day for six months, describing this as “a wartime bridge to increase oil supply until production ramps up later this year.”

This is only the second time that the SPR has been used for the purpose Congress intended in 1975 – to counteract temporary spikes in the global price of oil due to cartel extortion or foreign wars. The first time was during the Gulf War, on January 16, 1991, when President George H.W. Bush announced the SPR would immediately begin selling up to 2.5 million barrels a day. On the following day, The Washington Post reported, “The price of crude oil plunged by one-third today, falling a record $10.56 a barrel to levels not seen since last summer. The dramatic sell-off to $21.44 shocked traders and led several oil companies to announce immediate price cuts.” With the price falling below $20 (where it remained for eight years), the SPR ended up selling much less than expected, about 17 million barrels.

The 1975 law establishing a strategic reserve proposed drawing down as much as necessary if “there is a significant reduction in supply which… [results in a] severe increase in the price of petroleum products… likely to cause a major adverse impact on the national economy.” Aside from 1991, however, the SPR has only been rarely and gingerly used for various other purposes unrelated to oil prices, such as hurricane assistance or raising funds for the recent infrastructure bill.

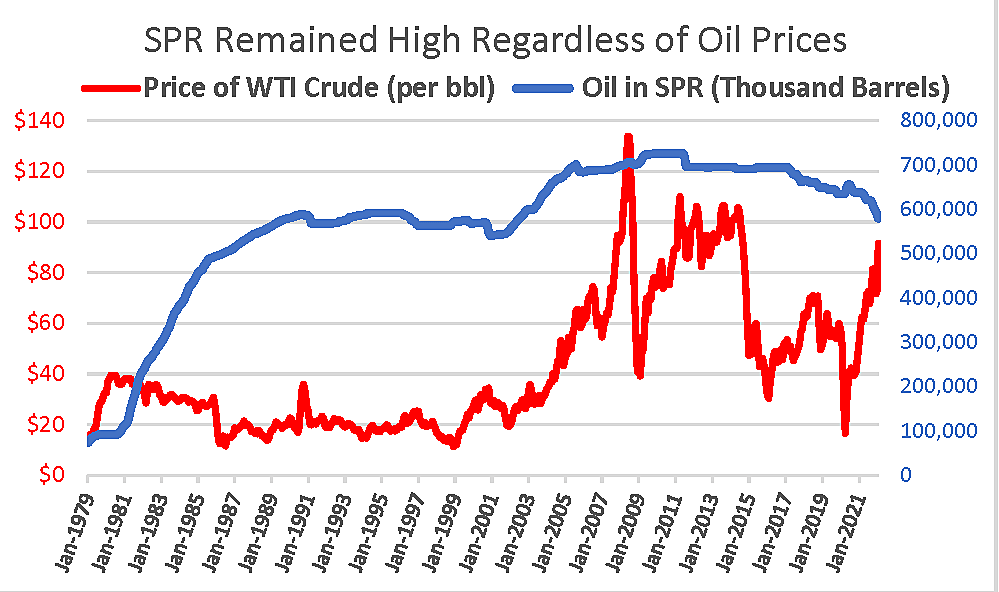

If the “Strategic” reserve had any strategy it appeared to be buying high (in 2007-08) and selling low (in 2020).

The blue line in the graph shows how the Strategic Petroleum Reserve kept adding to reserves by buying oil at rising prices during huge oil price spikes since 1979–82 and even while the price of West Texas Intermediate (WTI) crude oil often exceeded $100 a barrel from 2008 to 2014.

The SPR began as reaction to an abrupt and dramatic oil price shock after the Arab Oil Embargo announced on October 17, 1973 in response to U.S. support of Israel and the deep devaluation of the dollar. But the reason global oil prices soared was not because the U.S. was embargoed, as the sponsors of the SPR believed, but because Arab oil exporters slashed production by 4.4 million barrels a day (mbd) –7.5%. The embargo leaked badly because countries not subject to the embargo could simply import Arab oil and then turn a profit by diverting non-Arab oil to the U.S. at a higher price.

In fact, U.S. oil imports rose from 125 million barrels in September 1973 to 132.2 million in November and did not fall much until OPEC began raising prices in January 1974. From January to September of 1974 the U.S. imported 1.07 million barrels (at $11.12 a barrel) – slightly more than the 1.025 million barrels imported in the same pre-embargo months of 1973 (at $3.01) despite a deep recession starting in December 1973.

The critically important lesson of the so-called embargo of 1973 is that oil prices depend on the entire world supply and demand – not on one nation’s “energy independence” as President Nixon then imagined and most Fox News commentators still do. The U.S. recession from November 1973 to March 1975 was triggered by a global oil price shock, not a county-specific “shortage” of oil. But the economic damage was greatly aggravated by price controls, rationing, and by the Federal Reserve raising the fed funds rate from 10% to 13.5% by July 1974.

Unfortunately, those in charge of the SPR learned nothing from the global oil price shock of 1973–74 when we suffered two more of them from 1979 to 1982.

During the Iranian revolution, the price of WTI crude soared from $14.85 in January 1979 to $39.50 in April 1980 –and the U.S. economy fell into recession– as the supply of Iranian oil collapsed from 6 million barrels a day (mbd) to 1 or 2 million. Yet the SPR continued hectic buying oil for the reserve rather than selling. Once again during the first two peak years of the Iran-Iraq War (which began September 1980), the supply of Iraqi oil fell from 3.5 mbd to 1 million or less, and the U.S. economy fell into a deeper stagflationary recession. Yet the SPR continued hoarding more oil.

The SPR rapidly grew during two horrific stagflationary recessions – from 73.1 million barrels in January 1979 to 290 million by December 1982. The SPR oil inventory strategy in the early 1980s became, in effect, a price support program for OPEC oil.

During the biggest oil spike of them all –“The Oil Shock of 2007–2008″– not a drop of SPR oil was ever released. On the contrary, the SPR kept growing larger by bidding for increasingly expensive oil. The price of WTI crude oil soared from $50 a barrel in January 2007 to $133 by July 2008 – triggering The Great Recession (with the help of massive quantitative tightening by the Fed). The SPR stockpile rose from 688.6 million barrels in January 2007 to over 707 million by mid-2008 when oil prices reached a record.

Leaving the impression that officials were willing only to add to the petroleum reserve (regardless of price) and to never to sell without ample public warning, successive governments made it too easy for oil traders to favor momentum bets on rising oil prices (with call options) with negligible risk of a 1991-style surprise sale from the SPR.

For similar reasons, President Biden’s too-predictable plan to release reserves regardless of price is almost as non-strategic as previous plans to add to reserves regardless of price. This is like playing Texas Hold’em with many savvy traders while keeping all your cards face up.

Wall Street Journal editors complain that “the oil will need to be replaced, which will push up future demand” –as though the concept of “selling high and buying low” is incomprehensible or impossible. Replacing reserves need not push the price back up significantly if reserves were quietly and unpredictably replaced over time whenever the price is attractively low. The notion that replacing reserves in the future nullifies selling them today assumes the replacement is a mandated automatic “exchange” on a fixed calendar, as it was with the President’s small release last November, rather than conditional on the market price when the deals are struck.

If the Biden Administration is just trying to lower “prices at the pump” in an election year, as cynics suppose, that would be a misuse of the SPR and bad economics. The real threat of big oil spikes is to the cost of production and distribution, not just the cost of driving. The biggest oil spikes were followed by global recessions in 1973, 1980–82, 1990, 2000 and 2008.

However, the SPR was clearly intended to offset such economic risks from severe price spikes due to foreign supply disturbances. The Russian war on Ukraine fits that description even if the oil price may not yet be frighteningly high in real terms.