Government spending growth is directly related to expansions in the scope of government. As government scope expands, limits on spending and debt growth become an important backstop to further government expansion. The new Congress will be confronted with the U.S. debt limit sometime in 2023. Before nonchalantly increasing the debt limit, lawmakers should first adopt spending reforms to control spending and debt growth in the future.

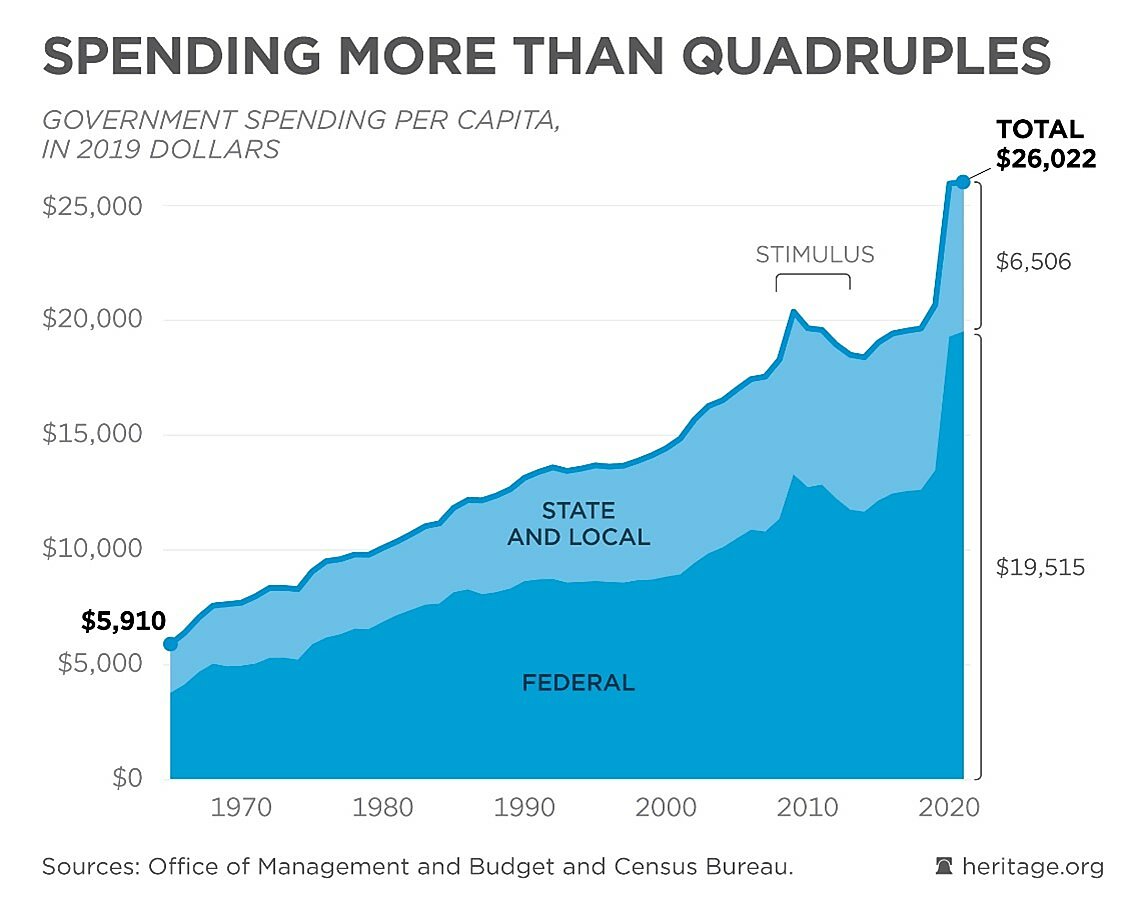

Government spending per person, after adjusting for inflation, has more than quadrupled over the past five decades. And while COVID-related spending will wind down over the next few years, a trend of increased government spending at all levels (federal, state, and local) is readily apparent.

(You can find more visual representations of federal budget trends and take a quiz to test your knowledge of the drivers of growing spending and debt by visiting The Federal Budget in Pictures at The Heritage Foundation—a project I led for many years.)

As federal spending has grown so has government debt. Federal debt, including publicly held debt as well as intragovernmental debt, recently exceeded $31 trillion or 130 percent of U.S. gross domestic product (GDP).

How do we stop the perpetual and unfunded growth in government spending that is driving the federal debt to unsustainable heights? Mark Moses, author of The Municipal Financial Crisis: A Framework for Understanding and Fixing Government Budgeting recently joined the Cato Daily Podcast. Moses emphasizes the importance of controlling the scope of government operations to limit spending growth. He laments the limitations of top-down approaches like revenue limits or balanced budget requirements because they don’t address the drivers of spending. His proposal to sustainably limit the growth in government: “Legislate limitations on scope and things that encourage very cautious consideration when scope is expanded.”

I don’t disagree. But what if that train has long left the station?

The federal government has vastly expanded in scope. Federal bureaucrats are involved in too many things that would be done better by individuals or businesses in the private sector, or by state and local governments—or that should not be done at all. The enactment of federal social and economic programs, largely originating with Social Security in 1935, followed by the Great Society programs in the mid-sixties, and subsequent expansions and additions, are the primary drivers of federal growth in size and scope. John Cogan covers this development eloquently in his book, The High Cost of Good Intentions: A History of U.S. Federal Entitlement Programs. He argues:

You can’t understand the growth in government without understanding entitlements. And they have truly, truly changed the priorities of our government from one that was primarily focused on national defense to one that’s now primarily focused on transferring hundreds of billions of dollars from one group in society to another group in society. And, most often, without regard to the financial need of recipients.

While inflation-adjusted defense spending has remained relatively flat, nondefense spending on entitlements and other social and economic programs, has expanded significantly. Human wants and needs are unlimited, and a government that tries to cater to every human want and need will inevitably become unbound.

Cato’s James A. Dorn traces this development to government trampling all over the Framers’ constitutional bounds. He writes:

When government oversteps the constitutional limits that protect persons and property in order to pursue what Hayek (1976) called the “mirage of social justice,” virtue is replaced by compulsion, democracy overrides limited government, and the spontaneous order of the market is impaired.

Modern U.S. liberals (so-called progressives) see the role of government to “do good” (with other people’s money) rather than to “do no harm.” Instead of asking whether the rules are just, they ask whether the outcomes are fair. This change from a focus on justice as protection of property to justice as the redistribution of property to satisfy special interests has undermined the Constitution as a charter of freedom. [emphasis added]

Legislative spending limits and balanced budget requirements are an important backstop to governments’ propensity to expand and amass unsustainable debt with perpetual deficit spending. Such top-down limits become especially important to rein in government attempts to meet an expanding set of priorities.

Spending limits, when upheld, incentivize better prioritization. When funds are limited, lawmakers are more pressed to allocate scarce resources toward more essential uses. Funding constraints also provide cover to say no to parochial projects that states, local entities, or private sector groups could take on—without federal government involvement.

Well-designed balanced budget requirements paired with legislative spending limits encourage long-run fiscal sustainability. Other countries, that are much older than the U.S., have managed to adopt sustainable fiscal practices after first letting spending and debt get out of hand. Three examples: Germany, Sweden, and Switzerland. These nations adopted transparent, sustainable fiscal frameworks that rest on popular support and reflect a bipartisan commitment to control the growth in the debt. Their fiscal rules are based on debt and spending targets that adjust with the business cycle and allow for a responsible emergency response. These countries’ experiences can be a model for U.S. policy.

As the federal government has reached far beyond its proper constitutional domain, excessive spending, taxing, and regulating distorts economic activity in numerous ways, leading to less growth and reduced prosperity. Controlling the growth in government requires limiting size and scope. Fiscal rules that limit the size of government by halting expansions in spending and debt are especially essential as the scope of government expands.

The new Congress will be confronted with the U.S. debt limit sometime in 2023. Lawmakers should seize this action-forcing mechanism to adopt effective spending limits to control the growth in the U.S. federal budget. They should set the stage for Medicare and Social Security reform (the largest drivers of U.S. spending growth) as well as adopt a more effective mechanism to re-evaluate other social and economic programs that are outside the proper scope of the federal government, such as a government reform BRAC (Base Closure and Realignment Commission (BRAC). I’ll explore these concepts in greater depth in future posts.